Taiwan in Time: Nov. 16 to Nov. 22

Having already been sentenced to death in absentia and with the Japanese colonial police closing in, Liao Tien-ting (廖添丁) still met an unexpected end in a cave in what is today New Taipei City’s Bali District (八里). On the run after a three-month crime spree, the most common version of events is that Liao was betrayed by his friend Yang Lin (楊林), who informed the police about Liao’s whereabouts. Liao tried to shoot Yang upon realizing the truth, but the bullet got stuck. Yang picked up a nearby hoe and crushed Liao’s skull. It was 1909, and Liao was 26 years old.

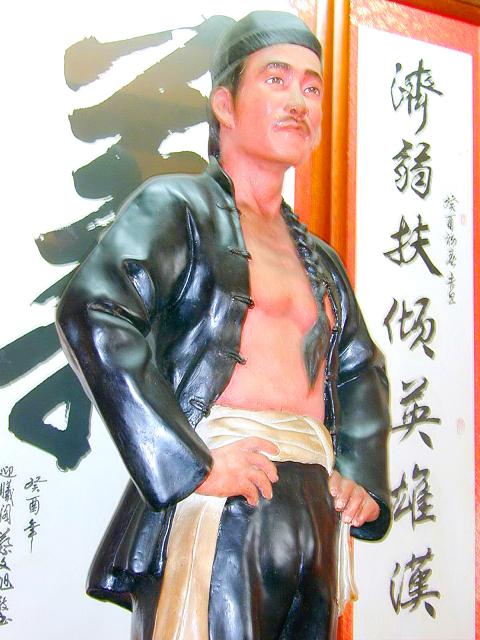

There are probably as many versions of Liao’s death as there are of his life and legacy, and even the day of his death, Nov. 18, is disputed. After all, who knows what’s real or not about this anti-Japanese folk hero — often considered Taiwan’s Robin Hood — whose story has been adapted into countless children’s books, novels, television programs and even an orchestral suite and Cloud Gate Dance Theatre (雲門舞集) performance. He’s worshipped at the Liao Tien-ting Temple (廖添丁廟) in Bali — which also houses his grave — and in other places such as the Xia Hai City God Temple (霞海城隍廟) in Taipei.

Photo: Ou Su-mei, Taipei Times

Even the story about his gravestone is legendary. It’s said that shortly after Liao’s death, the wife of a Japanese officer who pursued Liao became ill. Desperate to seek a cure, the officer followed local advice to pray at Liao’s burial place and his wife recovered soon after. The officer then erected the gravestone and worshipped Liao as a foster son.

In July this year, the Taipei District Court displayed for the first time a verdict sentencing Liao to death for the killing of alleged police informant Chen Liang-chiu (陳良久), even though Liao died before he could be arrested. To the Japanese at that time, he was no more than a robber and murderer, but to Taiwanese it was a completely different matter.

According to the Taiwan Daily News (台灣日日新報), a newspaper published during the Japanese colonial era, people visited and prayed at Liao’s grave regularly, believing that as a ghost he could cure sickness and perform other miracles. A January 1910 article stated that there was no more space in front of the grave to place joss sticks. The Japanese banned the practice in March that year, but Liao’s legend simply kept growing as an yizei (義賊, righteous criminal) who fought against colonial injustice by robbing the rich and giving to the poor.

Photo: Chang Jui-chen, Taipei Times

His heroic deeds and extraordinary abilities are still celebrated today, as a children’s book published in 2008 depicts some of Liao’s most famous moments, including saving an old man from police brutality with the throw of a pebble, robbing a man who made his fortune by colluding with the Japanese, jumping out of windows, flying over roofs and disguising himself as an old lady while being pursued. Other books show Liao being involved in anti-Japanese organizations, one even stating that both his parents were killed in a Japanese invasion of their village.

Born in today’s Taichung in 1883, Liao was 12 years old when Taiwan became part of Japan. His household registry shows that he was sentenced in 1902 to 10 months and 15 days in prison for larceny, his third offense. Some say he was locked up between 1905 and 1909 for his fifth offense, and others say he continued committing minor robberies and thefts during that time.

Liao’s final spree began in July 1909, including an incident on Aug. 20 where he and several accomplices stole guns, ammunition and a sword from two police dormitories. He also killed Chen during this time, frequently making headlines as the man who just could not be caught. After committing his final string of robberies in early November, Liao fled to the cave where he ultimately met his end.

That’s all that is certain about Liao’s life; the rest probably grew out of embellishments by locals, who reconstructed Liao as a spiritual hero to ease their frustration against their colonial masters — after all, who doesn’t like stories where the oppressors are terrorized?

Historian Tsai Chin-tang (蔡錦堂) says that Liao’s legendary abilities are mostly likely rooted in newspaper reports detailing his elusiveness, including how he jumped out of a moving train, fell into a valley and survived.

After his death, Liao made headlines a few more times, including one about people claiming to have seen his ghost. His crime spree was also adapted by a Japanese playwright in 1911.

As to the story that he was Taiwan’s Robin Hood, there is no concrete evidence that Liao gave his loot to the poor. But as early as 1914, a Taiwanese opera script about Liao was published, already bearing the “righteous outlaw” moniker.

After the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) took over Taiwan, Liao’s image transformed once more — this time into an anti-Japanese hero. But things didn’t stop there, as he was well on the road to deification.

There had already been many supernatural tales about Liao, including the one with the Japanese officer and others about his spirit appearing here and there to administer justice. People at that time believed that if a vigorous person died, he would become a powerful ghost, and started praying at his grave for various reasons, including health and fortune. Another belief was that someone who died a violent or unnatural death would become a ligui (厲鬼, vengeful ghost) and must be pacified through worship.

Liao’s grave was rebuilt after the Japanese left and worshipping resumed. Interest in Liao grew after a feature film was made about his life in 1956, and a small shrine was built around his resting place in 1958.

Locals tried to expand the temple with Liao as the main deity in the 1970s, but the government rejected the proposal due to lack of historic evidence of his heroic deeds. The temple was still built, but with Guan Gong (關公), also a real-life hero-type, as the main deity and Liao as secondary. Nevertheless, most people refer to it as the Liao Tien-ting Temple, and with its completion in 1975, Liao had completed his journey from wanted criminal to a worshipped deity.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand