English-language cookbooks featuring specifically Taiwanese food are a rarity — a search on Amazon.com yields just four entries, three of them published within the past three years.

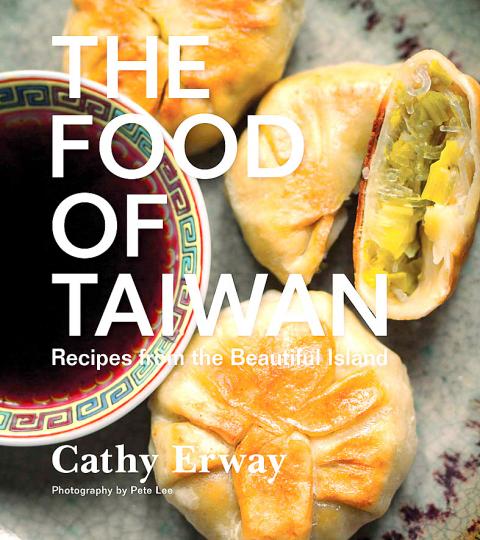

The most recent one, The Food of Taiwan: Recipes from the Beautiful Island, is an effort by New York City-based food writer Cathy Erway, whose mother is Taiwanese.

Erway’s previous book, The Art of Eating In contains more than just recipes — it’s a memoir that chronicles the two years she swore off restaurants. Her latest effort is similar — before delving into mouth-watering favorites such as beef noodle soup and pork belly buns, she talks about her personal connection to Taiwan and provides background information on the country. Even through the recipes section, she gives tidbits of information to allow the reader to better understand the various influences that have shaped Taiwan.

NATIONAL CUISINE?

It’s hard not to mention the meaning and definition of Taiwanese identity in any book introducing the country. This is brought up as early as the foreword by fellow food writer and Taiwanese-American Joy Wang.

“The issue of national identity in Taiwan is oftentimes fraught with caveats,” Huang writes. “While explaining all of that is cumbersome, the awareness of those caveats means that for many, even those of us who never grew up in the country, history is always close at hand.”

Erway begins her story in March 2004 when she witnesses the mass protests in front of the Presidential Office Building two days after president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) was re-elected.

She recalls being handed a fried pork bun (水煎包) and wondering how good protest-rally food could be.

“Of course it was good — this was Taiwan,” she writes.

Taiwanese cuisine left a deep impression on Erway, who found that most of her experiences in the country included food. Through her stay in Taiwan, she also learned about what makes her mother’s homeland a unique place.

Erway tries to stay impartial in explaining the political situation of Taiwan, as she says she has no strong political beliefs.

For example, she writes, “Is China Taiwan’s founding father or ultimate foe? A bullish presence and insult to democratic agendas, or a great economic opportunity and cultural kin? Who am I to say?”

Despite the political tension and identity issues, Erway says she noticed a growing sense of Taiwanese pride. Yet is there a unified culture? What exactly is Taiwanese cuisine?

While Erway explores the answer through the book, she says she sees the book as “only the beginning of a larger dialogue” of an “endless and ever expanding topic” as Taiwanese food continues to evolve.

HISTORY OF TAIWAN

The next few chapters provide brief but informative overviews of various aspects of Taiwan’s past and present, interspersed with scenic and vibrant photographs by Pete Lee.

The history section is comprehensive and thorough, yet Erway mistakenly describes the 228 Incident as resistance to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) “invasion” of Taiwan in 1947. In fact, the KMT had ruled Taiwan since 1945, and the incident was a violent government suppression of a local uprising.

But enough of that. Food is the main topic here.

Erway says she focuses on dishes that use ingredients that can be found in America, or can be easily substituted. This makes sense on one level, making the cuisine more accessible, but also runs the danger of being inauthentic.

It turns out, however, that the substitutions are mostly harmless — using cornstarch instead of sweet potato starch (though, if available, she calls the latter a “secret weapon for perfecting Taiwanese cuisine,”) Italian basil in place of its Asian counterpart and Japanese sake in place of Taiwanese rice wine.

Recipes

The recipes, which begin with appetizers and street snacks and end with desserts, are straightforward and easy to follow, and include background information about the origins of the dish.

For example, Erway mentions how chili sauce with Sichuan peppercorns didn’t become popular in Taiwan until the Chinese came in the mid-1990s, Hakka influences on pork belly buns and the Hokkien origins of oyster omelets (蚵仔煎). There are purely Taiwanese inventions — such as coffin bread (棺材板), that make use of foreign ingredients such as white bread. She discusses how beef noodle soup is believed to have originated in military dependants villages (眷村) and the Aboriginal practice of steaming sticky rice in bamboo logs. We start to see why it is so hard to define Taiwanese cuisine, or culture, as a whole.

In between entries, Erway continues her exploration with entries such as an overview of the country’s night market culture and post-1949 Chinese influences on local cuisine as well as musings on the definition and appeal of the texture Taiwanese refer to as “Q” (“springy and bouncy”) and why stinky tofu is unsuitable to make in a home kitchen. Unfortunately, due to the organization of the book, these entries may be easy to overlook if one is simply looking for recipes and not flipping through the book in its entirety.

Overall, despite its billing as a cookbook, The Food of Taiwan never becomes a pure list of recipes, and readers will learn about the author’s connections and feelings toward her maternal homeland and gain a deeper understanding of what makes Taiwan what it is.

If you just want to use it as a cookbook, though, it’s still a wonderful resource.

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand