Emperor Hirohito’s voice could be heard through radios across the Japanese Empire that day, including Taiwan. Not everyone had radios back then, but those who did didn’t hesitate to spread the news. It was Aug. 15, 1945, and Japan had officially announced its surrender to the Allies.

A much contested outcome of the Cairo Declaration of 1943 is that Taiwan, which Qing Dynasty China ceded to Japan in the treaty of Shimonoseki following its defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War, would return to China, then ruled by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT).

Although KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) appointed Chen Yi (陳儀) as governor general of Taiwan on Aug. 29, Chen didn’t land until Oct. 24. The next day, he formally accepted the Japanese governor-general’s surrender.

Photo courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

While the KMT was busy planning its arrival, what was going on in Taiwan between Aug. 15 and Oct. 25?

AFTER THE SURRENDER

The Taiwanese attitude toward the newcomers varies depending on who you ask, and will not be discussed here. Most sources agree, though, that the majority of people were more than happy to see the Japanese go.

Photos: Han Cheung,Taipei Times

Sources point to a short-lived Taiwanese independence attempt right after the surrender was announced, where Japanese military officers allegedly plotted with prominent Taiwanese to resist the Chinese takeover, though the level of Taiwanese involvement is disputed. This plan was abandoned just a week later after governor-general Ando Rikishi publicly warned against any such actions.

Historian and author Tseng Chien-min (曾建民) writes in 1945: Taiwan at Daybreak (1945: 破曉時候的台灣) that at least for the first 20 days, all Japanese colonial government activities went on as usual, as if nothing had changed. Tseng says that it was the Japanese police and members of the Japan-friendly volunteer fighting corps who kept social order during that time.

Because of that, Tseng says that Taiwanese were wary of celebrating openly at first, only doing so after the surrender was formally signed on Sept. 2.

Photo: Han Cheung,Taipei Times

Tseng says that as Japanese power waned, social order fell into the hands of local groups such as the Three Principles Youth Group (三民主義青年團).

According to History of Taiwan under Japanese Rule by Suemitsu Kazuya, on Sept. 1, 18 US and Chinese soldiers and officials arrived to liberate surviving Allied prisoners of war. More US troops landed for the same purpose on Sept. 5 and Sept. 7.

On Sept. 14, staff with the Taiwan Takeover Preparation Committee (台灣接收準備委員會) landed, making contact with the remaining Japanese military. Between Sept. 20 and Sept. 26, between 200 and 300 KMT troops occupied airports in Taipei, Taichung, Chiayi and Pingtung.

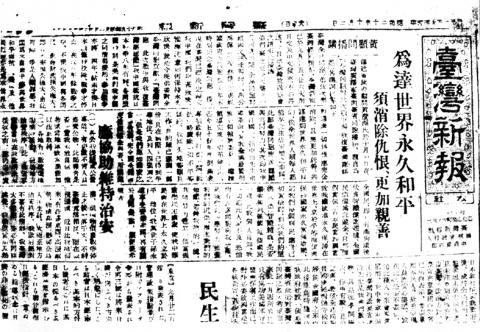

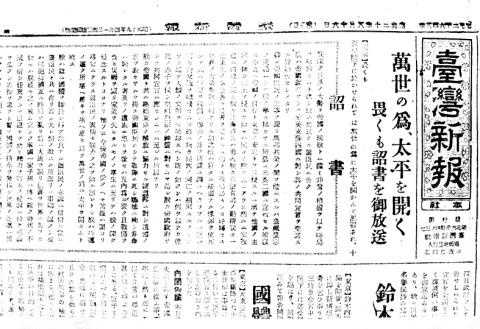

Taiwan’s only newspaper at that time, the Japanese-language Taiwan Shin Pao (台灣新報) published its first Chinese article on Oct. 2. By Oct. 10, Chinese had become the paper’s main language.

The entirely Chinese Min Pao (民報) was established on Oct. 10, and was known for being progressive and outspoken.

Committees to welcome the new government sprung up in various cities, making and delivering Republic of China (ROC) flags to offices and schools, putting up patriotic banners and teaching locals to speak Mandarin. According to a Min Pao article, almost 4,000 people showed up to a Mandarin class on Oct. 21.

What many call the “government-less” period lasted until Oct. 6, when the Taiwan Garrison Command’s (台灣警備總司令部) forward command (前進指揮所) arrived. It immediately issued several orders, including that administrative and legal functions were to still be carried out by the Japanese governor-general’s office until Chen Yi’s arrival and that all public functions such as traffic and mail should remain operating as usual. Education was to continue as before, with the exception that anything that challenged the ROC’s “status or educational philosophy” should be deleted.

Taiwanese observed Double Ten National Day for the first time with a huge celebration at the Taipei Public Assembly Hall, which is now Zhongshan Hall (中山堂).

More troops continued to arrive in Taiwan over the following few weeks, and spirits remained high, paving the way for Chen Yi’s big day. What happened in the next few years is another story.

OTHER EVENTS THIS WEEK IN HISTORY

Construction on the Sun Yat-sen Freeway began on Aug. 14, 1971, taking seven years to complete. Two oft-visited spots in the country opened to the public on Aug. 10, 1979: Leofoo Village Safari Park (六福村野生動物園) and Provincial Highway 2, better known as North Coastal Highway (北部濱海公路).

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

Jan. 12 to Jan. 18 At the start of an Indigenous heritage tour of Beitou District (北投) in Taipei, I was handed a sheet of paper titled Ritual Song for the Various Peoples of Tamsui (淡水各社祭祀歌). The lyrics were in Chinese with no literal meaning, accompanied by romanized pronunciation that sounded closer to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) than any Indigenous language. The translation explained that the song offered food and drink to one’s ancestors and wished for a bountiful harvest and deer hunting season. The program moved through sites related to the Ketagalan, a collective term for the