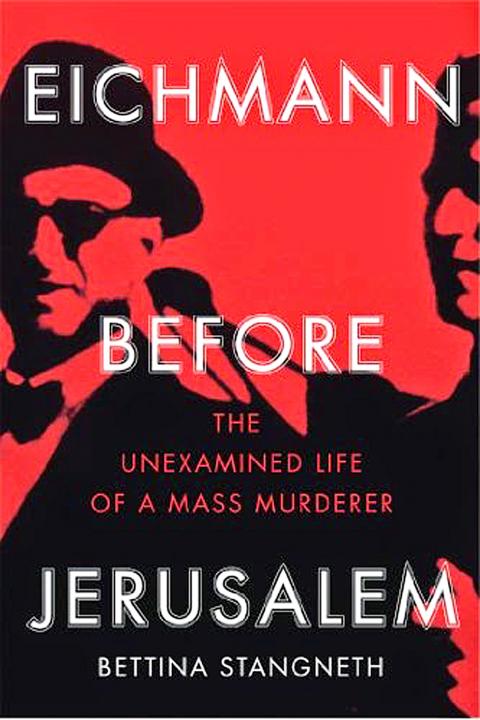

Before the war, Adolf Eichmann, born in 1906, was the acknowledged “Jewish expert” of the SS, in charge of carrying out various schemes to remove the Jews from Germany, such as encouraging — or forcing — them to emigrate, or transporting them to Madagascar. When the Germans invaded first Poland in 1939, then the Soviet Union two years later, Eichmann organized the concentration of the millions of Jews who lived in eastern Europe into ghettos, and then ensured they were taken, along with Jews from every part of Europe under Nazi control or influence, to camps such as Auschwitz, to be murdered. After Germany’s defeat, Eichmann went underground and then escaped to Argentina, where he joined a number of other senior Nazis in exile, living under an assumed name. During the 1950s, however, his whereabouts were discovered, and, in 1960, he was kidnapped by Mossad agents and smuggled out to Jerusalem, where he was put on trial for mass murder, found guilty, and, in 1962, hanged.

During his trial, as he sat in the bullet-proof glass box that served as the dock, Eichmann did not give the impression of being a monster, a sadist or a thug. He presented himself, on the contrary, as an ordinary, reasonable man. He was not personally, physically brutal or violent. When he had visited the scenes of extermination, he had clearly felt rather queasy. Yet here was a man who, notoriously, had said towards the end of the war that if Germany lost, he would “leap laughing into the grave because the feeling that he had 5 million enemies of the Reich on his conscience would be for him a source of extraordinary satisfaction.”

So what kind of a man was Adolf Eichmann? How and why did he become a mass murderer? The first and still the most famous and influential attempt to answer these questions came from the German-Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt, who attended the trial as a correspondent for the New Yorker, subsequently publishing her articles in a revised book-length version as Eichmann in Jerusalem. The book stirred up a storm of criticism, particularly though not exclusively from Jewish intellectuals in the US. There were many reasons for this. Reflecting what was known at the time, and in common with other early historians of the Nazis’ genocide of the Jews, Arendt was highly critical both of the passivity of the great majority of European Jews in the face of persecution and extermination, and of the collaborationist administration of the Jewish Councils in the ghettos, whose tragic and impossible situation failed to arouse her sympathy.

In the conversations he had with Sassen and others, Eichmann was completely unrepentant about the extermination of the Jews, which he saw as historically necessary, a policy he was proud to have carried out in the interests of Germany. The cynicism, inhumanity, lack of pity and moral self-deception of the conversations are breathtaking. This is a very disturbing book, and every now and then, as you read it, you have to pause in disbelief. Ten years and more after the war’s end, Eichmann’s lack of realism, typical for a political exile, even persuaded him that he could make a comeback, or that nazism could be rehabilitated, and he planned to launch a public defence of what he saw as its achievements.

In one of the conversations, Eichmann described himself as a “cautious bureaucrat” but also “a fanatical warrior, fighting for the freedom of my blood.” Stangneth dissents from Arendt’s belief that Eichmann was unintelligent, and points out that he calculatedly presented himself only as the cautious bureaucrat during his trial, deliberately concealing his “fanatical” side. But his clumsy attempt to present himself as pursuing a Kantian “categorical imperative” does not show that he was in any way an intellectual; and his mendacious self-presentation as a mere pen-pusher did not convince anyone, least of all Arendt. What he lacked was moral intelligence, the ability to judge the system he worked for and whose ideology he assimilated so completely.

Stangneth’s absorbing account of his years in exile adds considerably to our knowledge of Eichmann, but it is not a “total reassessment of the man,” as the publishers claim, nor is it true to claim that the book “permanently undermines Hannah Arendt’s notion of the ‘banality of evil.’” Half a century after it was written, Arendt’s book, despite the fact that it has been overtaken in many of its details by research, remains a classic that everyone interested in the crimes of nazism has to confront.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she