Woman and Home: In the Name of Asian Female Artists (女人-家: 以亞洲女性藝術之名) opens with a period piece of an upper-class Taiwanese woman.

Orchid (香蘭), which dates to 1968, is a late-in-life work by Hsinchu native and pioneering female artist Chen Chin (陳進).

Chen portrays an unvexed connection between woman and the home. A slender woman poses alone on a chair, her cool complexion and jade accessories allowing her to blend into her sitting room and match a nearby pot of white orchids. Altogether, they are a pictorial representation of the Chinese character for a woman getting married (嫁) — woman (女) and home (家) in natural union.

Photo: Enru Lin, Taipei Times

This painting provides an instant reference for comparison, as the relationship between the home and Asian women becomes complex and sometimes turbulent in the Greater Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Art’s later galleries. The exhibition is on display until Sept. 4.

HOME IS WHERE THERE ARE NO MISTAKES

Featuring mostly contemporary art by Asian female artists, Women and Home is a picture of how modern women view their connection with the domestic sphere.

Photo: Enru Lin, Taipei Times

It’s a 48-artist showcase of paintings, sculptures, films and installations, including outstanding pieces on loan from Japan’s Fukuoka Art Museum.

In a gallery themed Knitting and Weaving, pieces of makeshift furniture make the case for home as a positive space of reproduction. Labay Eyong turned recycled textiles and iron into a lounge chair, and Chinese sculptor Yin Xiuzhen (尹秀珍) created hundreds of book titles out of old clothing.

Filipina artist Marina Cruz is represented by the Unfold Series (2010), in which home is lovelier when viewed from afar. Arranged along two walls are photographs of her mother and aunt’s childhood clothing, laminated as if they were historic documents of a permanent museum collection. Each garment is inscribed with handwritten notes about the fabric, the girl it belonged to (“Sonia was a little big and a little dark when she wore this dress”) and other descriptions of incidents barely notable when they had occurred, but now imbued with a gravely and beautiful import.

Photo: Enru Lin, Taipei Times

In Wu Ma-li’s (吳瑪?) Sweeties of the Century (世紀小甜心, 1995-2000), home and its homemaker are the great equalizers. The title’s sweeties are a long row of framed portraits: Lee Teng-hui (李登輝), Michael Jackson, Franz Kafka and other icons of the 20th century as gap-toothed and tow-headed children. Set in this material space of the home, each famous face is fresh slate, free of all the achievements and the mistakes ahead and barely recognizable.

‘KNOW THE EFFECTS OF NUCLEAR EXPLOSIONS’

In other works, home is less restorative and becomes instead a site of entrapment and subtle exploitation.

Photo: Enru Lin, Taipei Times

Gao Yuan’s (高媛) 12 Moons (2009) is a portrait series featuring 12 Chinese migrant mothers posing with infants in their rapidly developing urban neighborhood. The mother-child pair and their home are symbiotic, as the nursing mother provides labor for the city and urban wages enable her to rear the child. Yet the difference in tone between the subdued Madonna figure and the spectacular composite backdrop is striking and reflects which side in the relationship has benefited more.

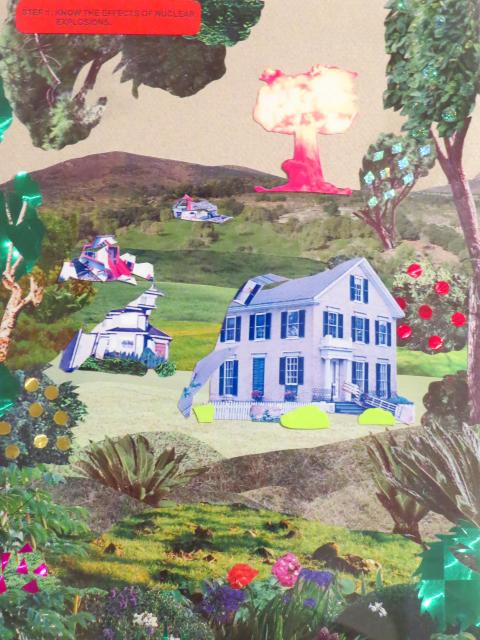

Tu Pei-shih (杜珮詩) parodies the modern-day ladies’ magazine with Eleven Steps Toward Happiness (邁向幸福的11步驟, 2008), eleven vivid collages featuring written directions for happy homemaking.

The work starts with a pop-art picture of western-style houses, bucolic hills and a mushroom-shaped explosion in the far corner (Step One: Know the effects of nuclear explosions). Next in the sequence are similar utopian scenes with advice for coping with menacing disasters.

Following these directions would confer more anxiety than happiness, and Eleven Steps is a tongue-in-cheek reproach of the “expert” who uses the concept of home and its attendant obligations to control the mind and movements of the womanly subject.

In this piece at least, the identity of the expert is left ambiguous and ungendered, and no other artist in the show directly addresses men, other women, specific institutions or demographics that have played a historic role in gender-based oppression.

This curatorial decision prevents the show from ever becoming provocative or even feminist, and is inseparable from the politics of the artists themselves, who may not have been prepared to be feminist in the way of demanding social justice. In that sense, this exhibition stays true to its goal of surveying women in the region. One half-century after images like Orchid, Woman and Home does not celebrate a revolution in social consciousness, but offers instead an unvarnished picture of women in Asia slowly and continuously struggling with what home means, who they can be and how to talk about it.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she