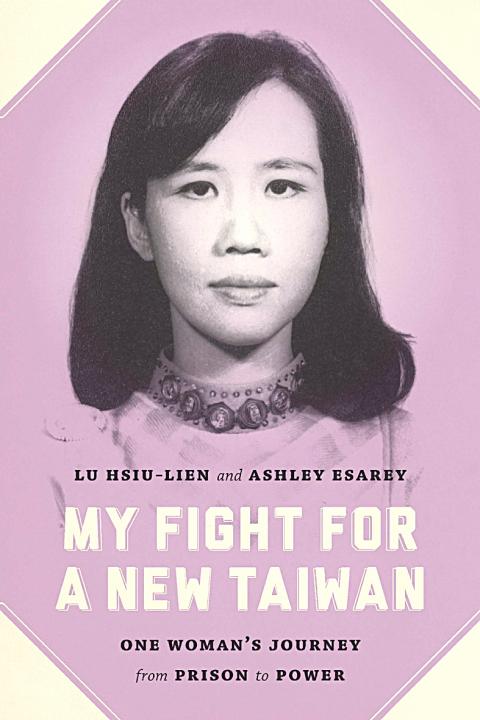

MY Fight for a New Taiwan, former vice president Annette Lu’s (呂秀蓮) recently published English-language memoir, departs from the classic narratives that politicians write after leaving high elected office.

Unlike VP memoirs such as Standing Firm (Dan Quayle) and In My Time (Dick Cheney), Lu’s new narrative is not really about publicizing underreported successes or settling old scores with foes she made during past terms. Neither is it about addressing the administration’s controversies, in the way of Lee Teng-hui’s A Witness for God (為主作見證).

In fact, Lu leaves out all the details of her eight-year term, a decision that means former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) is mentioned only as a supporting character in her pre-VP life — first as a young lawyer in the Kaohsiung Incident and later as a star in the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) who chooses her as running mate.

Their historic victory in 2000 bookends the memoir, appearing in chapter one (“Dreams Come True”) and then once more in an epilogue by cowriter Ashley Esarey, who summarizes the key events of the Chen administration with a brisk and light hand.

The chapters in between are all about what happened before 2000, but they turn out to be more interesting than a lot of post-term political memoirs.

The basic story is a reprise of something familiar to many Taiwanese voters. The unwanted daughter of a shopkeeper proves a brilliant student, a prisoner of conscience and then Taiwan’s first female vice president, in that order.

But Lu also delves into moments of her life that are far less storied. There was a stint as a newspaper columnist, during which she received a few letters of encouragement but mostly furious personal attacks.

She tried her hand at running a coffeeshop with a feminist bent, as well as sharing a “schizophrenic” leadership of a women’s group with a Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) member. There was an aborted romance with “Frank,” an overseas Taiwanese man she rejected when she discovered that, in the end, she could not shake off her traditional notions of what a man should be.

“He wasn’t the dashing, cosmopolitan diplomat-to-be I had envisioned,” she writes of her dismay after meeting him for the first time.

‘Dystopian’ politics

In one of the strangest sections of the book, Lu recounts her time in local politics, during which she found herself trying to resolve problems existing in the Taoyuan County Council — whose history, she tells us, resembled a “dystopian crime novel” — and the great “trash crisis,” which resulted in her leading garbage trucks on the search for a suitable dump in the middle of the night.

The book is darker when it turns to the Kaohsiung Incident, which is one moment in national history that, for most foreign observers and Taiwanese alike, is slightly murky.

Lu was jailed for a little over five years for her role, and she provides a lucid play-by-play of the clash between pro-democracy protesters and police on Dec. 10, 1979. She writes in detail about how male suspects were tortured, and how she provided police with confession after confession after months of subtle sexual harassment and other intimidation.

Lu also speaks directly of her tensions with other leaders in the Kaohsiung Incident, who she says exposed her to danger by leaving her out while they made plans together.

Throughout the narrative, Lu is never on totally friendly ground with the DPP and its predecessor, the dangwai (黨外, “outside the party”) movement, which refers to politically active dissidents that weren’t allowed to form political parties during much of the Martial Law era. Later, her first vice-presidential bid is thwarted by her party members, and at Lee Teng-hui’s National Affairs Conference she is again betrayed by her party members, who she says struck deals with the ruling party without her, “patting each other on the back like brothers.”

Tough skin

What emerges from these episodes is a feminist story, of a woman trying to break into a political system dominated by men. It’s also simply the tale of one person’s droll responses to setbacks.

Lu willfully takes everything as a compliment, including Beijing’s cry that she was the “scum of the nation” for the pro-independence remarks she made upon her vice presidential election. (“Such a big country has to use all its resources to insult Annette Lu. Isn’t that an honor?”) Unbacked at home in her efforts to promote Taiwan abroad, she was happy to engage in increasingly creative diplomacy, such as dispatching a paddleboat and a banner reading: “Welcome Taiwan into the UN!” past the window of Jiang Zemin (江澤民).

It is easy to want to pore over this book for clues about Lu’s future plans or her relationship with Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), the presumptive presidential nominee for 2016 — but this does not look like that kind of political memoir, either.

Lu makes a glancing mention of her ideas on constitutional reform, which her party rejected at the National Affairs Conference, but besides that, this book is silent on where Taiwan is headed in the future. Instead, My Fight for a New Taiwan is a standalone story that is limited in scope, with ambitions to be little more than an engrossing story of a life devoted to Taiwan, which regardless of its success in achieving its goals remains a remarkable journey.

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

The consensus on the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair race is that Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) ran a populist, ideological back-to-basics campaign and soundly defeated former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), the candidate backed by the big institutional players. Cheng tapped into a wave of popular enthusiasm within the KMT, while the institutional players’ get-out-the-vote abilities fell flat, suggesting their power has weakened significantly. Yet, a closer look at the race paints a more complicated picture, raising questions about some analysts’ conclusions, including my own. TURNOUT Here is a surprising statistic: Turnout was 130,678, or 39.46 percent of the 331,145 eligible party

The classic warmth of a good old-fashioned izakaya beckons you in, all cozy nooks and dark wood finishes, as tables order a third round and waiters sling tapas-sized bites and assorted — sometimes unidentifiable — skewered meats. But there’s a romantic hush about this Ximending (西門町) hotspot, with cocktails savored, plating elegant and never rushed and daters and diners lit by candlelight and chandelier. Each chair is mismatched and the assorted tables appear to be the fanciest picks from a nearby flea market. A naked sewing mannequin stands in a dimly lit corner, adorned with antique mirrors and draped foliage

The election of Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) as chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) marked a triumphant return of pride in the “Chinese” in the party name. Cheng wants Taiwanese to be proud to call themselves Chinese again. The unambiguous winner was a return to the KMT ideology that formed in the early 2000s under then chairman Lien Chan (連戰) and president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) put into practice as far as he could, until ultimately thwarted by hundreds of thousands of protestors thronging the streets in what became known as the Sunflower movement in 2014. Cheng is an unambiguous Chinese ethnonationalist,