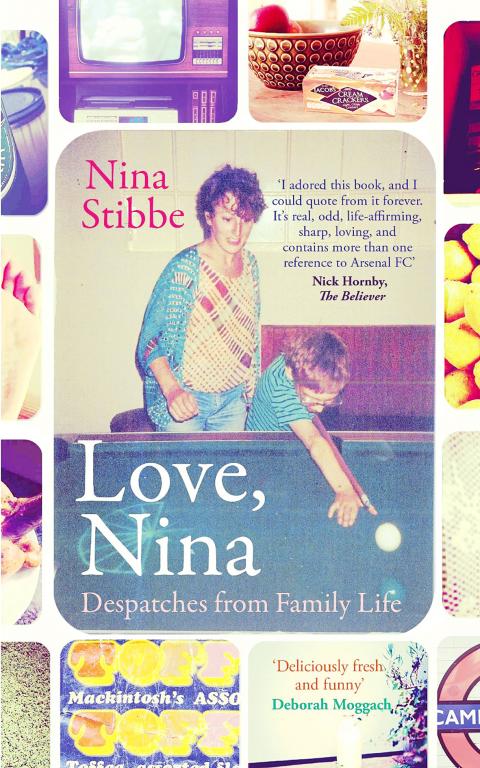

I do judge books by their covers, sometimes, and the one on Love, Nina made me place it in the “probably not” pile. Its bright watercolor artwork (kids, bicycle, vaguely European street scene) suggests a book that’s trying too hard, in the Peter Mayle vein, to be adorable. The subtitle, “A Nanny Writes Home,” doesn’t dispel this impression.

Here, you think, is a book that wants to throttle you with its charm, as if intended to appeal to the owners of bookstores that mostly stock potpourri, clip-on reading lamps and complicated bookmarks.

Mea maxima culpa. It turns out that Love, Nina is indeed charming, but only in the best ways. It’s observant, funny, terse, at times a bit rude. It affords a glimpse into a rarefied London social and literary milieu. It’s an Upstairs, Downstairs or Downton Abbey of sorts, set not in a manor house but in the genteel bohemian home of Mary-Kay Wilmers, the longtime editor of The London Review of Books.

Nina Stibbe was 20 in 1982, when she was hired by Wilmers to be the nanny to her young sons, Will and Sam. Wilmers was a single mother; her sons were the product of her marriage to the film director Stephen Frears, which had ended in divorce.

Stibbe moved to London from Leicestershire to take the position. She missed her sister, Victoria, who worked in a nursing home. So the two began exchanging letters. The author’s side of this correspondence, written from 1982 to 1987, makes up the entirety of Love, Nina.

These letters are winning from the start. Stibbe describes being a nanny as “not like a job really, just like living in someone else’s life.” She quickly realizes that she’s come to live with one of those families whose daily life has a bit of unfussy magic in it.

The Wilmers house is art-filled. Everyone is amusing and curses a lot. Evenings are spent flipping through dictionaries and arguing about, for example, whether “brim” is a better word than “flank” and “how to offend — in German and English.” This is the kind of book in which a pair of cheap curtains are likely to be described as “very ‘Mike Leigh.’”

Neighbors and friends are constantly dropping by, notably Alan Bennett, the playwright and London Review diarist, who seems to arrive every other night for dinner, and Claire Tomalin, the biographer and journalist.

Stibbe was not much of a cook when she arrived in London. Many of the best bits in her letters detail her running battles with Bennett, “AB” in this volume, over how best to prepare a variety of dishes. The author often gives us verbatim dialogue, such as:

AB: Very nice, but you don’t really want tinned tomatoes in a beef stew.

ME: It’s a Hunter’s Stew.

AB: You don’t want tinned tomatoes in it, whoever’s it is.

Wilmers, “MK” here, seems like a somewhat warmer version of Miranda Priestly, the imperious magazine editor in The Devil Wears Prada. She’s skinny; she smokes; she brings her floppy-haired boyfriends around; she stares at the ceiling when she wants to let you know you’re being an idiot.

She loathes platitudes. Stibbe says, “I remember once, in 1982, asking MK if she’d had a nice weekend and I could see it didn’t go down well so never asked again.”

When a friend presents Wilmers with wind chimes said to ward off bad spirits, she doesn’t want them, Stibbe says, because “(a) she doesn’t like tinkling noises and (b) she’s not 100 percent anti bad spirits.”

Some of the better moments in this epistolary memoir involve discussions of sex, most of which are more or less unprintable here. When Stibbe catches Will and Sam watching a bit of porn on video, even its title is oddly winsome: Best Bit of Crumpet Out of Denmark.

Mostly, though, we simply like being in Stibbe’s company. She comes to realize why so many mothers are “cold and annoyed” — it’s from walking around in supermarkets. She won’t do yoga because “I might not do so well as a relaxed person.”

I enjoyed her take on fiction over here in the States: “When you read American fiction you get to accept all sorts of names that were unthinkable before. Dick, Frank, Milo, Chuck, Micky, Dick, Biff, Willie, Gullie, Happy, Augie, Fritz, Artie, Woody, Rocky, Bill.” (This bit is linked to her observation that most men’s names sound like penises or toilets or worse.)

We like Stibbe more for not being Mary Poppins. She dents Wilmer’s car and neglects to tell her about it. She dodges fares on the tube. She pushes Sam in the pool when he won’t go in. Wilmers constantly says things to her like, “How can we ever believe a word you say?”

The pleasures in Love, Nina are modest but very real. It’s a book that may put readers in mind of Helene Hanff’s 84, Charing Cross Road (1970), that volume of discursive correspondence between a book lover in New York and the staff of an antiquarian bookshop in London.

It’s a book that makes you wish Wilmers would write a proper memoir, one that might detail the many things not mentioned here: her upbringing in a cosmopolitan, itinerant Jewish family; her time at Oxford along with Bennett; her young adulthood in London in the Swinging 1960s and ‘70s; the way she has reportedly pumped millions of dollars from her family trust into keeping The London Review afloat.

It seems appropriate to end a review of this brisk book with a few of Wilmers’ words. When an acquaintance — here called Brainbox — drops by the house unexpectedly, the moment is captured this way:

Brainbox: Hello, Mary-Kay!

MK: Oh, right.

BB: Can’t stay long.

MK: Good.

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any

You can tell a lot about a generation from the contents of their cool box: nowadays the barbecue ice bucket is likely to be filled with hard seltzers, non-alcoholic beers and fluorescent BuzzBallz — a particular favorite among Gen Z. Two decades ago, it was WKD, Bacardi Breezers and the odd Smirnoff Ice bobbing in a puddle of melted ice. And while nostalgia may have brought back some alcopops, the new wave of ready-to-drink (RTD) options look and taste noticeably different. It is not just the drinks that have changed, but drinking habits too, driven in part by more health-conscious consumers and