In the 1930s, rich European expatriates loved imperial China for its culture — its opera, its scholarship and its incomparable graphic arts. But as this collection of 28 recollections consistently shows, nowadays foreign enthusiasts for the PRC face an emphatically different land, one characterized by endless shopping-malls, protracted drinking sessions, road-side dumplings, shadeless urban boulevards, corruption, pollution and the inescapable results of the one-child policy.

When I first got hold of Unsavory Elements I thought I was going to be bored. Surely what it would consist of would be predictable language teachers’ tales of their avaricious employers, unadventurous students, and wild exploits on their days off. But this turned out to be far from the case.

To begin with, there are some distinguished contributors here. Admittedly there’s no Paul Theroux, Jan Morris or Colin Thubron. But Peter Hessler contributes a piece on the view over the border into North Korea, admittedly reprinted from The New Yorker in 2000, and Simon Winchester has written an Epilogue. Many other writers included here have books to their names, and by and large language-teacher angst is thankfully in short supply.

The piece that’s attracted most attention is the last, by the book’s editor Tom Carter. It describes a visit to a bar that offered no drinks, only young and not very attractive prostitutes. A grotesquely impolite Canadian and a Kenyan choose to take three girls between them, Carter having opted out on the grounds that he had a girlfriend. The Canadian fails to achieve orgasm due to excessive alcohol intake, while the girl the Kenyan choses wants to take a photo of his member on her cell-phone.

Someone online has complained that the story exploits very young Asian girls in a way the American author should be ashamed of. It seems to me, however, to portray an aspect of life in the PRC that would otherwise have gone unrepresented, and the undoubted humor of the narrative makes it seem, all in all, unobjectionable.

For the rest, there’s an account of his time in a Shanghai jail by a hashish-smuggler, another of life in a Shenzhen hospital following a knife-attack, and a story by the well-known Hong Kong humorist Nury Vittachi about someone being enticed into an underground Beijing bar and relieved of 100 Euros.

All the chapters are around 10 pages long, and inevitably some are more gripping than others. These are the tales I found most memorable.

First there was a fragment by Jeff Fuchs about journeying the so-called Ancient Tea Horse Road from Lhasa to Yunnan Province. This was enthralling, and Fuchs has published a book with the same Tea Horse title. Then came a narrative by Pete Spurrier, excellently written, about traveling from Urumqi to Hong Kong by train, mostly without a ticket.

Also memorable was an account by Susie Gordon of a night in the company of some of Shanghai’s ultra-rich that included eight bottles of wine at an unbelievable $RMB60,000 a bottle, followed by champagne, 60-year-old baijiu, cocaine and marijuana. Girls were laid on, though one of the party preferred to look for gay contacts via a cruising app.

I was surprised to discover that a story about a Westerner mistakenly trying to win a drinking contest in Chengdu had been penned by Derek Sandhaus, the redoubtable editor of Trelawny Backhouse’s extraordinary Decadence Mandchoue [reviewed in the Taipei Times Oct. 17, 2013]. What was surprising was that Sandhaus was listed as actually living in Chengdu itself, where he “writes about Chinese alcohol and drinking culture.”

Politics only surface occasionally, though the Chinese Communist Party is ever-present beneath the surface. Singaporean Audra Wang, for example, writes about approaching Tibet from Gansu on a reporting assignment just after the anti-government riots in Lhasa and elsewhere in March 2008. Michael Meyer writes about roller-blading to Tiananmen Square, while Deborah Fallows tries to visit the same location on the 20th anniversary of the 1989 crack-down.

Ohio’s Jocelyn Eikenburg has an interesting piece about being a Western woman dating a local (“From the first time I started to love a Chinese man, hiding became a part of my life”).

For the rest, there are tales of buying a pair of shoes for a one-legged child; playing ice-hockey, with on-pitch fights, in Dalien; appearing as a rock ‘n’ roll band at a music festival 200 miles into the wilds from Chongqing (a “megalopolis of 35 million”); and trying to export 2,000 hand-painted kung-fu T-shirts to the US.

There are, as it happens, two pieces about teaching English. One tells of an offer of huge payments for penning essays to be offered by students as their own work when applying for colleges in the US, while another contains what may be a motto of almost universal validity in Asia, “My presence improved the school’s image, but nobody was interested in putting me to any good use.”

Especially engaging is a piece by Graham Earnshaw, who founded Earnshaw Books — this book’s publisher — in 1997, describing setting up a what’s on weekly on Shanghai the following year. It lasted only seven weeks, but the achievement, Earnshaw considers, was nonetheless historic, exemplifying the maxim that in the PRC “nothing is allowed but everything is possible”.

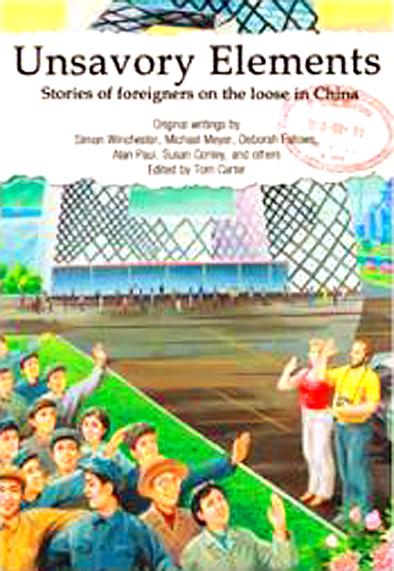

The book has an attractive cover with artwork by Nick Bonner and Dominic Johnson-Hill, though apparently with significant North Korean input.

Earnshaw remarks that in Shanghai’s supposedly golden age in the 1930s the city was full of just such “raffish foreigners” as he and his colleagues. Maybe the aesthetes tended to head for Beijing while the more unsavory elements preferred life in the newer port city to the south. Either way, though, the moral of this collection appears to be that though almost everything has changed, one basic thing — the allure of China to a certain kind of Westerner — remains curiously consistent.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she