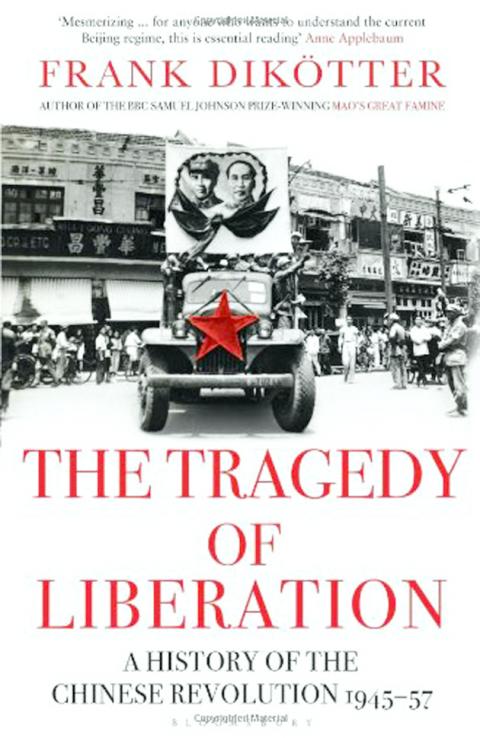

It’s a commonly-held opinion that all revolutions begin in gladness but eventually descend to despondency and madness (to quote Wordsworth). The French, Russian and Chinese revolutions, it’s thought, started with the people’s joy at the overthrow of the old regimes, but their attitudes later became characterized by a horror at the realities of the new ones.

Frank Dikotter, in the case of China’s revolution, begs to differ. Things were pretty much dreadful from the very start, he argues, and there’s little evidence of an initial “honeymoon” period.

This isn’t a book about contemporary China. The events surveyed happened 50 years and more ago, so any attempt to marshal ideas of the grim reality of the initial revolutionary period in any contemporary “neo-Cold War” polemic would be inappropriate. There isn’t even much disagreement in China itself over what constituted the reality in that far-off era.

This new book constitutes the initial volume in Dikotter’s projected “People’s Trilogy”, a three-volume project that kicks off with this present title, has his Mao’s Great Famine [reviewed in the Taipei Times September 12, 2010] in the middle, and will conclude with a book on the Cultural Revolution. Dikotter, in other words, began in the middle and has now completed the opening volume.

The general outline of these early, often brutal, years is probably well-enough known. There was the murder of landlords, the starving of previously pro-Nationalist cities into submission, the Terror that saw one in a thousand, perhaps more, killed as class enemies, the intimidation through confessions and “study-sessions,” and the sending of half a million intellectuals to labor camps in 1957. Alongside these were hugely ambitious economic programs that gave people reason to feel that life was indeed going to get better, and quickly.

There are some extraordinary details here, such as that Mao Zedong (毛澤東) drove to Beijing in 1949 in a bullet-proof Dodge limousine made in Detroit for Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) personal use in the 1930s. After the fall of Nanjing, the Nationalist capital, “Chen Yi (陳毅) and Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平) took turns sitting in Chaing Kai-shek’s chair.” But then the narrative is vivid and full of color everywhere, making this book a potential blockbuster as well as a piece of extensive historical research.

Dikotter’s historical summaries are also brisk. Few complained at the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950 — Britain had “lost interest in the region … since India had become independent,” and the UN “had their hands full with the Korean War.” There are few complexities here to perplex the general reader.

All in all, this book seems to represent something of a change of tone for Dikotter. Personal accounts are extensively used, and the prose style is markedly popular and accessible. There isn’t a boring paragraph anywhere, and considering that the author must have had to read through some boring primary material, he must simply have decided to leave most of it out. The benefit for the ordinary reader is immense. Dikotter has never been a dull writer, but here he appears to be reaching out for a mass readership. This book, you’ll note, is being published, like Mao’s Great Famine, by Bloomsbury, not by one of the increasingly pervasive university presses.

Readable, not entirely check-able, summaries abound. “People fled the rust-red plain in droves.” “Mao would agree to almost anything on paper, so long as nobody was checking what he was doing on the ground.” “Thousands of banners fluttered in the autumn breeze above a sea of people carefully selected from all walks of life.” “[Prostitutes] stood in the doorways openly soliciting customers: ‘Come in for a cup of tea!’” This is popular history and, though some academics may disdain it, it’s welcome to have Dikotter, a man whose research credentials are impeccable, trying his hand at the style so successfully.

Sometimes Dikotter’s research or his extensive reading comes up with a gem. Thus this, by a man tied onto a plank for denunciation: “I lay on the wooden plank looking up. The rain had stopped. Amid the loud shouting, I could hear the river nearby. The clouds had dispersed and the sky was clear blue. I thought ‘People lived harmoniously under the same sky in the same village for many years. Why did they act like this now?’”

Everything deemed relevant to the revolution is described in this book. In a chapter called “The Road to Serfdom”, for instance, Dikotter spells out the mechanics of collectivization. Earlier the campaign against Buddhists, Taoists and Christians, both Catholic and Protestant, is explained, and anti-Muslim sentiment detailed. We learn how books, the theater and cinema were all subject to rigorous censorship, with one publisher’s list being reduced from some 8,000 titles to just over 1,000 between 1950 and 1951, and how formerly eminent essayists, diplomats and liberals were systematically targeted. Little of this is new, but here Dikotter presents the evidence as part of a wide-reaching, very accessible story.

It therefore seems to me that what Frank Dikotter is doing in this trilogy is penning a comprehensive popular history of the revolution in China from its beginnings to what was effectively its close, the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976. It’s intended to be a popular work, something that will be read by millions in the English-speaking world just as Jan Morris’s Pax Britannica trilogy was, and still is, read, or the popular histories of A.J.P. Taylor. But this trilogy will be popular in a special sense. It may be highly readable (“enjoyable” is hardly an appropriate word in the circumstances), but all the time you know it’s the product of a major authority on the period. Its generalizations are rooted in knowledge that isn’t necessarily displayed on the page, and its colorful evocations of time and place are based on long hours in the archives. The whole trilogy when it’s completed is thus likely to be, and deserves to be, the book almost everyone will turn to first when seeking an outline of its momentous and ultimately tragic subject.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is