Some artists prefer not to talk about the value of their work. Damien Hirst clearly revels in it, going so far as to call art “the greatest currency in the world.”

On the eve of Hirst’s first major retrospective in his native Britain, he hit back at a leading critic who dismissed him as a conman and advised anyone owning his work to sell it fast.

Julian Spalding, a curator and critic who has just written a short book called Con Art — Why You Ought to Sell Your Damien Hirsts While You Can, went on the attack last week with articles in at least two national newspapers.

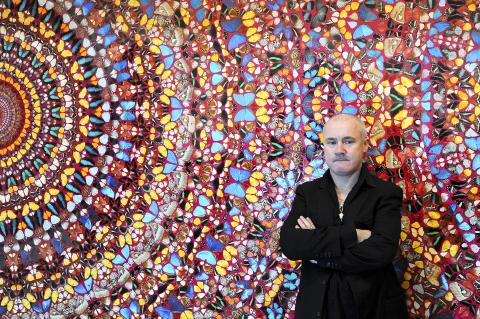

Photo: AFP

They were designed to coincide both with the release of his book and the opening this week of an exhibition at Tate Modern tracing Hirst’s journey from a student at Goldsmiths College, London, to the world’s most commercially successful living artist.

Spalding questioned whether Hirst, known for his shark suspended in formaldehyde, a diamond-encrusted skull, spot paintings and medicine cabinets, was an artist at all and described his works, which fetch millions at auction, as “worthless financially.”

Hirst, speaking on Monday to a small group of journalists at the Tate Modern gallery overlooking the river Thames, was clearly used to such jibes and brushed Spalding’s criticism aside with a grin.

Photo: Agencies

“It’s like, you say ‘sell your Hirst.’ I say ‘don’t sell your Hirsts, hang on to them.’ If you look at the numbers ...

“It’s always healthy to have both views — people love it, people hate it. I once said as long as they spell my name right I don’t mind. As I’ve got older I don’t really mind if they spell my name right either.

“Andy Warhol said that great thing didn’t he? ‘Don’t read your reviews, weigh them.’”

Photo: Agencies

SMELL OF DECAY AND MONEY

The fact that Hirst quoted Warhol was hardly surprising — both artists have been commercially canny and saw the value of their works as inextricably linked to the art itself.

Hirst’s spot paintings, for example, are made by employees and untouched by the artist, a fact that did not prevent them becoming status symbols for the rich and famous.

Photo: Agencies

The artist has come to embody the spirit of 1990s London where his works, often given intriguing titles, appealed to hedge fund managers and oligarchs as well as an art world clamoring for new ideas.

Championed early on by collector Charles Saatchi, Bristol-born Hirst personifies conspicuous consumption, yet the 46-year-old, with a fortune estimated at over US$320 million, insisted that the art came first.

“I’m one of those lucky artists that makes money in their lifetime, and makes lots of money,” he said. “I’m not afraid of that but I think the goal’s always been to make art and not money. Making money is a by-product, a very happy by-product.

Photo: Agencies

“I think art’s the greatest currency in the world. Gold, diamonds, art — I think they are equal ... I think it’s a great thing to invest in.”

The show itself focuses on some of Hirst’s most important early works with a view to putting his later series into context.

The first spot painting, for example, was made in 1986 and, instead of the precise grid of equally spaced, equally sized circles of different hues comes a slap-dash affair with paint dripping down a canvas of rows of irregular shapes.

Two years later Hirst conceived and curated the Freeze exhibition of his work and that of fellow students, an early and important step towards establishing him as the leading figure in the influential “Young British Artists” (YBA) movement.

By 1995 he was a famous artist, winning the coveted Turner Prize and, in his acceptance speech, reminding the world of his humble academic background and rebellious spirit.

“It’s amazing what you can do with an E in A-Level art, a twisted imagination and a chainsaw,” he said.

The chainsaw referred to Mother and Child, Divided, a bisected cow and calf which went on display at the Turner show and provoked widespread criticism.

Another Hirst work featuring a rotting cow and bull was banned in New York because of fears it would “prompt vomiting among visitors.”

It was leading US dealer Larry Gagosian who showcased Hirst in the US, presenting the No Sense of Absolute Corruption show in New York in 1996.

Hirst’s mother encouraged his passion for drawing as an adolescent, but was less tolerant of his taste in music and fashion — she melted one of his Sex Pistols albums into the shape of a fruit bowl, according to online biographies, and cut up his “bondage” trousers.

INSECT-O-CUTOR

Hirst’s famous “pickled” shark, entitled The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, stands in the middle of the Tate show, a reminder of how death has been a dominant theme throughout Hirst’s 25-year career.

Also familiar will be cabinets filled with medicine and his “spin” and butterfly paintings, but new to many will be In and Out of Love, a room in which butterflies hatch, live and die as the public passes through.

Visitors are asked to check they are not unwittingly carrying a part of the art work with them when they leave.

It shares some of the themes with A Thousand Years from 1990 in which maggots hatch inside a glass vitrine, develop into flies, feed on the severed head of a cow and meet their end on an “insect-o-cutor.”

A whiff of decaying flesh escapes from the glass container, to go with the odor of stale cigarette butts in his giant ash-tray Crematorium and the inescapable smell of money.

That is strongest towards the end of the show in a gold wallpapered room dedicated to Hirst’s record-breaking auction at Sotheby’s in 2008 where he raised US$177 million from more than 200 new works.

Called Beautiful Inside My Head Forever, it was a groundbreaking event, conceived as a single work of art that bypassed the dealers — and their hefty fees — altogether.

The Golden Calf, a bull in formaldehyde adorned with horns, hooves and a disk above its head made of 18-carat gold, raised US$16.5 million alone.

In the Tate’s gift shop is a limited edition plastic skull decorated in “household gloss” paint priced at US$59,000, while a roll of Hirst-designed wallpaper cost US$1,014.

There is also the chance to see his diamond-encrusted skull For the Love of God displayed in a blacked-out box in the cavernous Turbine Hall lit only by spotlights shining on the 8,601 flawless gems set in a platinum cast of a human skull.

The sculpture fetched the then equivalent of US$100 million in 2007, when it sold to a consortium of investors that included Hirst himself.

The artist has long avoided a retrospective, deeming it “more OAP” (old age pensioner) than YBA and worrying that his life’s work would “amount to nothing” once it went on display.

But Hirst finally accepted the idea and the exhibition is one of the highlights of the Cultural Olympiad which is based around this summer’s Olympic Games in London.

“I feel honoured to be given this slot and hopefully I’ve done it justice,” he said. “I definitely hope that more people walk away liking it than hating, but I’m not under any illusions that everyone’s going to love it.”

‧ Damien Hirst runs from today to Sept. 9.

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Aug. 25 to Aug. 31 Although Mr. Lin (林) had been married to his Japanese wife for a decade, their union was never legally recognized — and even their daughter was officially deemed illegitimate. During the first half of Japanese rule in Taiwan, only marriages between Japanese men and Taiwanese women were valid, unless the Taiwanese husband formally joined a Japanese household. In 1920, Lin took his frustrations directly to the Ministry of Home Affairs: “Since Japan took possession of Taiwan, we have obeyed the government’s directives and committed ourselves to breaking old Qing-era customs. Yet ... our marriages remain unrecognized,

During the Metal Ages, prior to the arrival of the Dutch and Chinese, a great shift took place in indigenous material culture. Glass and agate beads, introduced after 400BC, completely replaced Taiwanese nephrite (jade) as the ornamental materials of choice, anthropologist Liu Jiun-Yu (劉俊昱) of the University of Washington wrote in a 2023 article. He added of the island’s modern indigenous peoples: “They are the descendants of prehistoric Formosans but have no nephrite-using cultures.” Moderns squint at that dynamic era of trade and cultural change through the mutually supporting lenses of later settler-colonialism and imperial power, which treated the indigenous as

Standing on top of a small mountain, Kim Seung-ho gazes out over an expanse of paddy fields glowing in their autumn gold, the ripening grains swaying gently in the wind. In the distance, North Korea stretches beyond the horizon. “It’s so peaceful,” says the director of the DMZ Ecology Research Institute. “Over there, it used to be an artillery range, but since they stopped firing, the nature has become so beautiful.” The land before him is the demilitarized zone, or DMZ, a strip of land that runs across the Korean peninsula, dividing North and South Korea roughly along the 38th parallel north. This