How well should a historian write? That’s a complicated question, but it’s difficult to disagree with George Orwell, who thought that any exemplary book should not only be an intellectual but “also an aesthetic experience.”

Elaine Pagels, a professor of religion at Princeton University, possesses a calm, sane, supple voice. It’s among the reasons readers have stuck with her over a nearly four-decade career, often on hikes through arduous territory, like her commentary on ancient Christian works that were banned from the Bible. She’s America’s finest close reader of apocrypha.

Pagels is best known for The Gnostic Gospels (1979), which won a National Book Award and was named one of the best 100 English-language nonfiction books of the 20th century by the Modern Library. That book spawned a million biblical conspiracy theories, as well as The Da Vinci Code, Dan Brown’s hyperventilating novel. Few seem to hold that against her.

The cool authority of Pagels’ voice serves her almost too well in her new volume, Revelations: Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation. She surveys this most savage and peculiar book of the New Testament — an ancient text that is nonetheless, as novelist Will Self has put it, “the stuff of modern, psychotic nightmares” — as if she were touring the contents of an English garden. She’s as unruffled as the heroine of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, who declared in one of that excellent television show’s best episodes, “If the apocalypse comes, beep me.”

Her Revelations is a slim book that packs in dense layers of scholarship and meaning. The Book of Revelation, attributed by Pagels to John of Patmos, is the last book in the New Testament and the only one that’s apocalyptic rather than historical or morally prescriptive. It’s a sensorium of dreams and nightmares, of beasts and dragons. It contains prophecies of divine judgment upon the wicked and has terrified motel-room browsers of the Gideon Bible for decades.

Pagels places the book in the context of what she calls “wartime literature.” John had very likely witnessed the skirmishes in AD 66, when militant Jews, aflame with religious fervor, prepared to wage war against Rome for both its decadence and its occupation of Judea.

She deepens her assessment of the Book of Revelation by opening with a troubled personal note.

“I began this writing during a time of war,” she says, “when some who advocated war claimed to find its meaning in Revelation.”

Because he feared reprisals, John wrote this condemnation of Rome in florid code.

He “vividly evokes the horror of the Jewish war against Rome,” Pagels writes. “Just as the poet Marianne Moore says that poems are ‘imaginary gardens with real toads in them,’ John’s visions and monsters are meant to embody actual beings and events.” For example, most scholars now agree, she says, that the “number of the beast,” 666, spells out Emperor Nero’s imperial name.

The so-called Gnostic Gospels, the subject of Pagels’ breakthrough book, were discovered in 1945 at Nag Hammadi, in Upper Egypt. At that site scholars also found dozens of other previously unknown books of revelation. Among this volume’s central questions, then, is this one: How did John’s book of revelation become the only one included in the New Testament?

Pagels approaches this question from many angles but agrees with those scholars who have suggested that John’s revelations were less esoteric than many of the others, which were aimed at a spiritual elite. John was aiming at a broad public.

The others, she writes, “tend to prescribe arduous prayer, study and spiritual discipline, like Jewish mystical texts and esoteric Buddhist teachings, for those engaged in certain kinds of spiritual quest.”

What’s more, she writes, because John’s revelations end optimistically, in a new Jerusalem, not in total destruction, they speak not just to what we fear but also to “what we hope.”

John’s visions, throughout the centuries, have been applicable to almost every conflict or fit of us-against-the-world madness. Charles Manson read the Book of Revelation before his followers’ rampages; Hitler apparently read himself into the narrative as a holy redeemer, while the rest of the civilized world saw him as the book’s beast.

For a work that contemplates a hell made on Earth, Pagels’ book rarely produces much heat of its own. It drifts above the issues like an intellectual satellite.

One of her great gifts is much in abundance, however: her ability to ask, and answer, the plainest questions about her material without speaking down to her audience. She often pauses to ask things like, “Who wrote this book?” and “What is revelation?” and “What could these nightmare visions mean?” She must be a fiendishly good lecturer.

The Book of Revelation is not prized as being among the best-written sections of that literary anthology known as the New Testament, but Pagels is alive to how its language has percolated through history and literature. Jesus, who appears on a white horse to lead armies of angels into war, will “tread the winepress of the fury of the wrath of God,” John wrote.

This image emerges again in The Battle Hymn of the Republic, the Union’s anthem during the Civil War: “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord;/He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored.”

John’s book has caused great mischief in the world, Pagels suggests, but it is a volume that can be clasped for many purposes. It has given comfort to the downtrodden, yesterday and today.

John, Pagels writes, “wants to speak to the urgent question that people have asked throughout human history, wherever they first imagined divine justice: How long will evil prevail, and when will justice be done?”

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

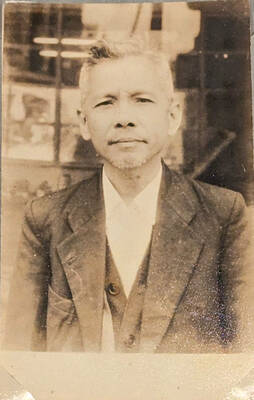

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name

There is no question that Tyrannosaurus rex got big. In fact, this fearsome dinosaur may have been Earth’s most massive land predator of all time. But the question of how quickly T. rex achieved its maximum size has been a matter of debate. A new study examining bone tissue microstructure in the leg bones of 17 fossil specimens concludes that Tyrannosaurus took about 40 years to reach its maximum size of roughly 8 tons, some 15 years more than previously estimated. As part of the study, the researchers identified previously unknown growth marks in these bones that could be seen only