Curated by German-born, France-based artist Monika Brugger, A Bit of Clay on the Skin brings together work from 18 jewelry artists from around the world. The exhibition runs until Feb. 5 at the New Taipei City Yingge Ceramics Museum and was organized by La Fondation Bernardaud, which is run by the Limoges luxury porcelain maker and seeks to enhance the profile of ceramics as a fine arts medium. The show opened at the Museum of Art and Design in New York City last year and will travel to Paris and Toronto.

Out of the artists represented by the exhibition, only one, Peter Hoogeboom, uses mainly ceramics in his creations. The Dutch artist’s work pioneered the use of ceramics in contemporary jewelry.

“I think he proved that you can work with ceramics and be avant-garde as well,” says Brugger. “He is completely trained as a jeweler and I think that is something very important. People trained as jewelers discover new materials and they have a completely different notion of what we can do.”

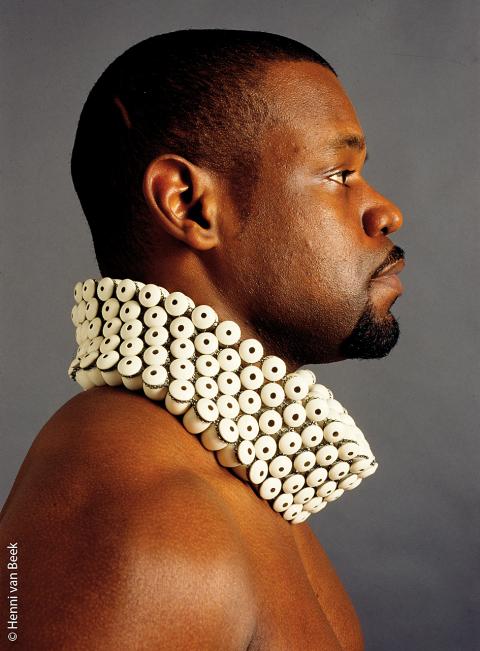

Photo courtesy of Peter Hoogeboom

A collar made from rows of perfectly uniform ceramic beads by Hoogeboom not only references the heavy collars created by some African ethnic groups, but also the elaborate starched ruffs worn by European aristocrats during the late Renaissance.

Finnish artist Tiina Rajakallio’s necklaces also offer an interpretation of historical jewelry and costume. Braided from human hair, her Purity series recalls the “sentimental” or mourning jewelry that was popular in Europe during the Victorian era. While sentimental jewelry was intricately woven from gleaming locks of human hair and mounted on gold, Rajakallio’s necklaces are made with cords of hair that look tangled and knotted. The rough texture is a contrast to jewelry “fittings” crafted from gleaming white porcelain, the same material used to manufacture bathroom fixtures.

Out of all the pieces in the exhibit, Rajakallio’s hair necklaces caused the most controversy during the selection process, says Brugger. She felt it was important to include the work because it challenges conventions of beauty.

Photo courtesy of Marie Pendaries

“The white [ceramic] pieces are the representation of propriety, something that is very hygienic,” says Brugger. “The hair, if you look really close, you can see some of it is not very clean.”

Other pieces are more conceptual in nature and borrow from the visual language of jewelry. The Dowry by French artist Marie Pendaries comprises 28 pieces of plain white crockery with holes of graduating sizes cut into them. They are worn assembled like weighty but fragile body armor. In a photo taken by Pendaries and included in the exhibit, the model laden with The Dowry poses with her palms together and eyes demurely facing away from the viewer, mimicking the posture of the Virgin Mary in portrayals of the Immaculate Conception.

The Dowry is among several works in the exhibition that use jewelry to comment on gender roles. Nymphes, French artist Carole Deltenre’s series of medallion pendants, is the most forthright, with white porcelain casts of vaginas surrounded by metal filigree.

Photo courtesy of Willemijn de Greef

“Traditionally you put the most important thing in medallions,” says Brugger. “Pictures, a lock of hair, something you find really important.”

Dutch artist Manon van Kouswijk’s Re:Model is cast from a mold of a classic pearl necklace. It has to be broken and the pieces strung back together again in order to be wearable.

“You have to crack it and ‘ruin’ the work, and then you can put it back together and wear it,” says Brugger. “Pearls symbolize purity. Members of the French bourgeoisie give necklaces to girls, but only after they are about 16 or 17, because it has to do with being a woman.”

Photo courtesy of Rian de Jong

Signet rings, traditionally worn by men as a symbol of authority, are also represented in the exhibition. Swiss artist Andi Gut’s rings are crafted from dental porcelain and steel. Gut was inspired by the similarities between tools used by jewelry makers and dentists, and the curvilinear shape of the signet rings echo the shape of teeth.

Taiwanese artist Shu-lin Wu (吳淑麟) used slip casting and mokume gane, a traditional Japanese metalworking technique that creates layered patterns similar to wood grain, to craft large, hollow beads and ceramic “stones.”

“[Ceramic] is warmer than metal and I felt the material is also representative of my origin. Historically in Taiwan and China we use a lot of ceramics,” says Wu.

Photo courtesy of Christoph Zellweger

The colors and shape of her beads, which are strung into necklaces, offer a modernized, abstract take on Wedgewood jasperware, which was also sculpted in layers. Wu’s earrings, however, are arranged into girandoles, which feature a central piece framed by two drops and two to three pendants dangling from the bottom. The classic style contrasts with Wu’s ceramic pieces, which have edges reminiscent of Neolithic stone implements instead of the symmetrical facets of modern gem-cutting.

Other jewelry artists in the exhibition offer their own take on art and design traditions. Dutch artist Evert Nijland’s porcelain necklaces were created as a response to architect Alfred Loos’ influential 1908 essay Ornament and Crime, which derided the overuse of meaningless decorative flourishes. Nijland’s porcelain pieces include a necklace with delicately sculpted flower buds and pastel colors reminiscent of rococo figurines and architecture strung onto a simple woven linen cord. Necklaces by another Dutch artist, Willemijn de Greef, are molded from terra cotta used to build houses in Zuiderzee, a fishing region in the northwest of the Netherlands, and sport floral motifs commonly seen in the area. De Greef’s pieces are outsized and have to be worn slung across the body. Many of the pieces in the exhibition straddle the line “between jewelry and installation,” says Brugger.

“It’s about jewelry and ornament, and the question of ‘what is ornament?’” she says. “What does it mean to ‘ornament’ somebody?”

Photo courtesy of Shu-lin Wu

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she