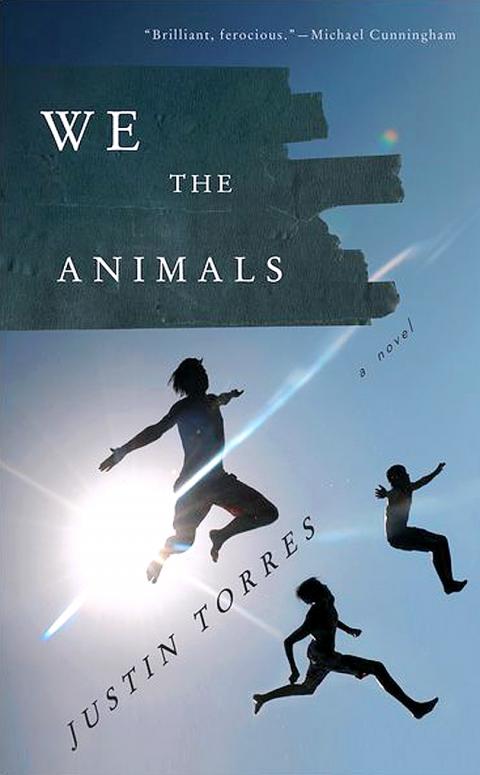

Dusk seems to be descending forever on the boys at the center of We the Animals, a slender but affecting debut novel by Justin Torres. As porch lights go on, and the other kids shamble home to chores and homework, the unnamed narrator and his brothers prowl the blighted streets of their rural hometown in upstate New York like stray dogs sniffing out their next meal or a new bit of trouble. At home the rising of the moon brings a mother’s absence — she works the night shift at the brewery — and a father’s frustration, which is relieved only by violence inflicted on whoever is at hand.

We the Animals, the kind of sensitive, carefully wrought autobiographical first novel that may soon be extinct from the mainstream publishing world, is mostly written in the first person plural, a tricky gambit that calls attention to itself immediately (as it did in Joshua Ferris’ best-selling novel of cubicled anomie, Then We Came to the End). But the device doesn’t impede our engagement with Torres’ spare, haunting story of a boy scrabbling toward wisdom about the adult world.

“We” are the three sons of a mixed-race couple, Ma and Paps, who met in Brooklyn in their youth before moving upstate, presumably in search of economic opportunity that hasn’t materialized. He is Puerto Rican; she is white. She was just 14, he 16 when she became pregnant; they had to take a bus to Texas so they could marry legally. (One of Torres’ few literary tics is a slight overuse of the semicolon in the early chapters; perhaps it’s catching?)

When the book begins the narrator is nearly 7, and his two brothers, Manny and Joel, are just a couple of years older. The boys travel in a pack, their ethnicity setting them apart from the white working-class children around them, and the disorder of their home life encouraging them to burrow further into their protective intimacy.

On the narrator’s seventh birthday Ma is languishing in bed, her face bloated and bruised days after a severe beating. (Paps had explained that the dentist did it: “He said that’s how they loosen up the teeth before they rip them out.”) When she wakes and realizes it is her youngest child’s birthday, she calls him to her and tells him why it’s his duty to remain 6 years old forever: “She whispered it all to me, her need so big, no softness anywhere, only Paps and boys turning into Paps.” To grow up is to grow hard.

The book is composed as a series of brief chapters moving roughly chronologically through a span of a little more than a half-dozen years. Telling incidents are described in simple language that occasionally rises to a keening lyricism: Paps teaching his wife and youngest boy to swim by abandoning them in deep water; Ma receding into catatonic despair when her husband disappears for a few days; a frenzied later attempt at escape when she piles the boys into the truck (the truck she hates for its lack of seatbelts) but drags them home again when they can think of no place to go.

“We had been terrified she might actually take us away from him this time but also thrilled with the wild possibility of change,” Torres writes. “Now, at the sight of our house, when it was safe to feel let down, we did.”

The scenes have the jumbled feel of homemade movies spliced together a little haphazardly, echoing the way memory works: Moments of fear or excitement sting with bright clarity years later, while the long passages in between dissolve into nothingness. From the patchwork emerges a narrative of emotional maturing and sexual awakening that is in many ways familiar (no prizes for guessing the nature of the sexual awakening in question) but is freshened by the ethnicity of the characters and their background, and the blunt economy of Torres’ writing, lit up by sudden flashes of pained insight.

A sense of lives doomed to struggle and disappointment pervades the writing without dragging it into lugubrious or melodramatic territory. Scenes that thrum with violence can suddenly turn tender too, and the brutality of their father’s behavior isn’t the whole story. In one striking scene he gives the boys a loving bath before suddenly turning his attention to his wife. The boys, still huddled in the tub, cower in silent awe and confusion as their parents begin to make love.

Although the boys’ lives seems to be circumscribed by their isolation from the world and their complicity in the chaos of their parents’ fraught marriage, change inevitably comes as adolescence steals up on the narrator. His sensitivity and bookishness puts unwanted distance between him and his brothers. Suddenly the “we” is fractured into “they” and “I”: “They smelled my difference — my sharp, sad, pansy scent.”

Torres, whose short story Reverting to a Wild State was recently published in The New Yorker, is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and now holds a prestigious Wallace Stegner Fellowship at Stanford University. He does not always avoid the kind of overly cultivated eloquence that announces a writer staking his claim for literary achievement.

Writing that calls attention to its own sophistication seems particularly unnecessary when Torres’ novel relates such an affecting story of love, loss and the irreversible trauma that a single event can bring to a family. As he writes with fine simplicity toward the end, when the shock of a secret revealed has drawn a sharp line between the narrator’s troubled past and his uncertain future, “Everything easy between me and my brothers and my mother and my father was lost.”

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a