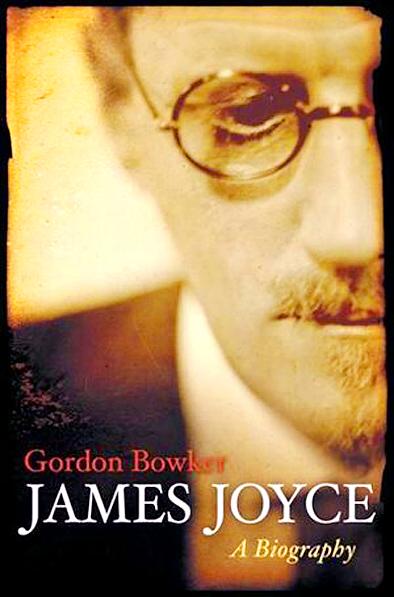

No book on James Joyce goes half as far as this one in establishing connections between passages in the classic texts and incidents in the artist’s life. Even Joyce’s uneasy struggle to exclude unflattering details from the first biography of him, by Herbert Gorman, is used to explain a passing reference in Finnegans Wake to a “biografiend.” What Joyce wanted was someone who would allow him control over every element of his reputation: a biografriend. Gorman, although he accepted the main interdictions — on family privacies — was not happy with the arrangement or the outcome. He insulted Joyce by failing to send him a copy of the published volume.

Gordon Bowker demonstrates just how comprehensively the artist also sought to control the first extended works of literary analysis on Ulysses. Joyce was a gifted “autocritic,” and even today Frank Budgen’s 1934 memoir about the making of Ulysses sparkles, because it is filled with the Dubliner’s table-talk. Stuart Gilbert, author of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1930), was somewhat more resistant to manipulation, keeping his reservations out of his study of Homeric analogies in the masterpiece, but filling a sardonic diary with sarcasms about the Joyce circle. Bowker, whose respect for the greatness of Joyce’s texts never wanes, is shrewd enough to include a liberal amount of these balancing judgments.

The strictest injunction laid on Gorman was also the last: that Joyce’s motivation in leaving Ireland never be disclosed. All subsequent biographies have accepted that Joyce made himself modern by abandoning Ireland as a cultural backwater disfigured by clerical oppression and a general censoriousness. The truth is more mundane but sadly prophetic of the fate of thousands of Irish graduates in the decades after Joyce: he simply could not find a post in the country commensurate with his qualifications, abilities and ambitions. So the flight with Nora Barnacle had to be re-branded as a dissident exercise in “silence, exile and cunning.”

Only once did Joyce deviate from this line. He told the painter Arthur Power that in the Dublin of his youth the British retained all power, with the consequence that ordinary people felt no responsibility for anything and were free to do or say what they wanted. Only with independence in 1922 emerged a nation of apple-lickers: people who, if tempted in the Garden of Eden, would have licked rather than bitten the apple.

Like all honest biographers before him, Bowker knows that turn-of-the-century Dublin was filled with intrepid artists and unfettered intellectuals. Yet somehow he feels compelled to support the common contention that the great man made himself thoroughly modern by ceasing to be knowingly Irish. Not so. To be Irish, in those days, was to be modern anyway, whether one wanted to be or not. Good educational opportunities along with chronic under-capitalization produced the formula for a major experimental culture.

Perhaps because he doesn’t rate modernist Dublin too highly, Bowker sometimes slips up on details — he sets the Cyclops episode of Ulysses in Davy Byrne’s rather than Barney Kiernan’s pub; he seems unaware that the burning of Cork city was due mainly to the Black and Tans; and his etymologies of Gaelic names can be dubious. On the credit side, he has been careful not to accept as fact details that were fictionalized by Joyce. He records, accurately, that Oliver Gogarty (the false friend who lived with Joyce for a time in the Martello Tower in Sandycove) was the son of a surgeon, whereas Richard Ellmann (taking Ulysses at its word) depicted him as a “counterjumper’s son” — that

is, the child of a sales assistant.

Ellmann was a brilliant

biographer and skilful interviewer, early enough on the scene to talk with many of Joyce’s acquaintances, some of whom told him untruths. Bowker, without fuss, fixes mistaken details. He also gives a more nuanced account of just how deeply Joyce’s years in Trieste influenced the shaping of Ulysses. Because it was a port city like Dublin on the edge of an already shaky empire and because it contained geniuses such as Italo Svevo, it filled Joyce’s head with ideas and characters.

This study will be valuable to students as a summation of our current biographical knowledge of Joyce. It captures recurring features of his art: a vaudevillian’s love of seaside settings, a delight in using children’s lore and nursery rhymes as portals of discovery, a compulsion to map his own family romance on to world history. It shows how difficult he could be even to his greatest admirers; yet it also evokes the heroism of a man who, confronted by poverty, ill health and endless uprootings, somehow found in himself the courage to write epics in celebration of ordinary people and the intricacies of their minds. It is in its way an example as well as an account of dignified audacity.

This doesn’t mean that Ellmann’s 1959 biography is passe. Not only did he write a beautiful prose, which no subsequent scholar has equaled, but he also had a fellow-artist’s understanding of the strange blend of facts, experiences, ideas and accidents which went into the creation of The Dead and Ulysses. Ellmann was one of the great literary critics of the last century and his biography, though long, implies a great deal more than it says. His account is of a flawed but decent man, who redeemed occasional misbehavior by the scale of his devotion to his family and to his work. Because its portrait contains much of the painter as well as the sitter, it will live forever as itself a work of art.

Joyce was restless, not only about biographies of him but sitting for portraits. When the painter Patrick Tuohy began to talk about the importance of capturing the Joycean soul, he muttered darkly: “Never mind my soul, Tuohy. Just make sure you get my tie right.” He would, for that reason, probably approve of Bowker’s book, which generally rests content with external detail but leaves the deeper acts of interpretation to others.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

Desperate dads meet in car parks to exchange packets; exhausted parents slip it into their kids’ drinks; families wait months for prescriptions buy it “off label.” But is it worth the risk? “The first time I gave him a gummy, I thought, ‘Oh my God, have I killed him?’ He just passed out in front of the TV. That never happens.” Jen remembers giving her son, David, six, melatonin to help him sleep. She got them from a friend, a pediatrician who gave them to her own child. “It was sort of hilarious. She had half a tub of gummies,