In Kung Fu Panda 2 the hero, a roly-poly panda named Po, voiced by the irrepressible Jack Black, undergoes an identity crisis. Raised by a doting, dithering, noodle-shop-owning goose, Po experiences flashbacks to a traumatic infancy, including hazy recollections of his parents that look sketched by hand, in contrast to the computer-polished, 3D images that dominate the movie.

As Po tries to work out his issues, Kung Fu Panda 2, directed by Jennifer Yuh Nelson from a screenplay by Jonathan Aibel and Glenn Berger, succumbs to its own crippling confusion. The first Kung Fu Panda, released in 2008, was a rambunctious, whimsical blend of action, jokiness and sentiment, lifted above the kiddie-cartoon mean by its shiny, playful look and Black’s endlessly adaptable charm. The movie was also a big enough hit to make it unthinkable that DreamWorks Animation, which ran poor Shrek into the ground, would let it stand alone. So the studio worked up this sequel, which accomplishes the depressingly familiar mathematical trick of being both more and less than its predecessor.

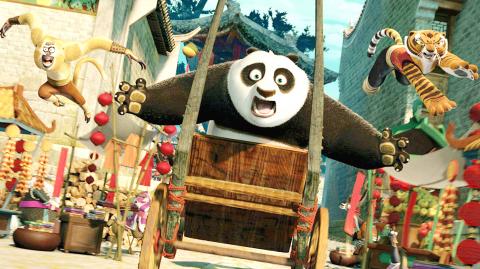

The upside of the “more” is that there is, once again, quite a lot of nice stuff to look at, an expanded palette of clever and sometimes beautiful visual effects. Like the first Panda picture — and like the intermittently sublime How to Train Your Dragon — Kung Fu Panda 2 uses 3D technology with flair and restraint, adding pop to the action sequences and depth to the landscapes, which evoke an ancient China spun out of candy.

Photo Courtesy of UIP

The palaces and villages, the mountains and bamboo forests, to say nothing of the beasts that populate this confectionary realm, are evidence of an affectionate, irreverent interest in Chinese artistic traditions. (Hans Zimmer’s score is a witty pastiche that includes some choice 1970s-style chopsocky riffs as well as more stately pseudoclassical swatches.) The movie is an obvious parody of sword and martial-arts wuxia (武俠) movies, but it also serves as an invitation to young audiences, who may find that Po’s antics have sparked an appetite for the more grown-up pleasures of movies like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (臥虎藏龍) or Curse of the Golden Flower (滿城盡帶黃金甲).

Vengeance and bloodshed figure prominently in many of those movies, and also, somewhat disconcertingly, in Kung Fu Panda 2. The villain, a peacock named Shen (with the reliably sinister voice of Gary Oldman), has not only usurped the imperial throne, aided by some nasty, armor-plated wolves; he has also conducted a campaign of genocide against pandas, an atrocity that figures in Po’s half-repressed memories. Apparently Po is the only surviving member of his species, which makes him both the target of Shen’s violence and an agent of righteous vengeance. I say “apparently” because an unexplained bit of revisionism at the end of the movie reveals that Shen’s panda slaughter was not as extensive as previously believed.

Have I spoiled anything? If you are 7, maybe. If not, I have spared you some uncomfortable explaining and allowed you to reassure panicky children in your company that everything will be OK. Everything always is in this kind of movie, but this one plays with some unusually dark and upsetting material.

Photo Courtesy of UIP

Its escalation of evil messes up the high-spirited sweetness that was the most winning feature of the first movie. Po’s clumsy, goofy eagerness no longer seems quite as amusing now that he is a psychologically damaged warrior. And his action-team entourage, drawn from various species of animal and movie star — praying mantis, tiger, monkey, etc; Seth Rogen, Angelina Jolie, Jackie Chan (成龍), etc — do more to crowd the picture than to enliven it. On the other hand, an elderly soothsayer voiced by Michelle Yeoh (楊紫瓊) steals every scene she’s in.

So all in all, Kung Fu Panda 2 is about what you would expect, and its audience is likely to settle for it in the absence of a compelling alternative. (“I’ve seen hundreds of movies that were better than that one,” said my 7-year-old screening companion, as if reading my mind.) Early on, Po’s teacher, speaking in the gravelly tones of Dustin Hoffman and doing a cool trick with a drop of water, advises his disciple to seek “inner peace.” “Inner piece of what?” Po asks. Of the box office grosses for Kung Fu Panda 3 and 4, I’d guess.

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Aug. 25 to Aug. 31 Although Mr. Lin (林) had been married to his Japanese wife for a decade, their union was never legally recognized — and even their daughter was officially deemed illegitimate. During the first half of Japanese rule in Taiwan, only marriages between Japanese men and Taiwanese women were valid, unless the Taiwanese husband formally joined a Japanese household. In 1920, Lin took his frustrations directly to the Ministry of Home Affairs: “Since Japan took possession of Taiwan, we have obeyed the government’s directives and committed ourselves to breaking old Qing-era customs. Yet ... our marriages remain unrecognized,

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

Standing on top of a small mountain, Kim Seung-ho gazes out over an expanse of paddy fields glowing in their autumn gold, the ripening grains swaying gently in the wind. In the distance, North Korea stretches beyond the horizon. “It’s so peaceful,” says the director of the DMZ Ecology Research Institute. “Over there, it used to be an artillery range, but since they stopped firing, the nature has become so beautiful.” The land before him is the demilitarized zone, or DMZ, a strip of land that runs across the Korean peninsula, dividing North and South Korea roughly along the 38th parallel north. This