Baoan Temple (保安宮) will hold birthday celebrations for the God of Agriculture (神農大帝) on Saturday as part of its 2011 Asia-Pacific Baosheng Cultural Festival (2011亞太保生文化節).

Festivities begin at 8am with a ritual for the deity, followed by several performances in front of the temple from 9am to noon, and continue at 1pm when a statue of the deity will be placed on a palanquin and escorted on an “inspection tour” (繞境) through Dalongdong District (大龍峒).

For those who can’t make it to the celebrations, Baoan Temple also arranges free tours in Japanese and English (or both) that last anywhere from 30 minutes to two hours.

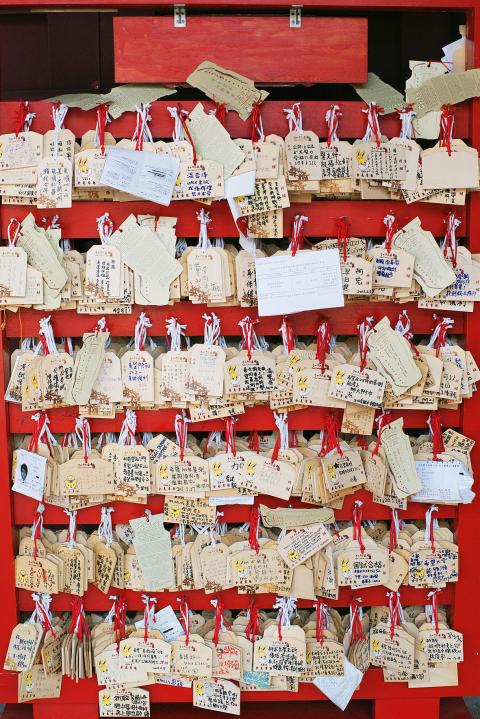

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

Baoan Temple and Taipei Confucius Temple (台北市孔廟), which is located across the street, have clued up to the fact that local culture, particularly temples and the communities that build up around them, rank among Taiwan’s most popular cultural assets. Read on for a description of the tours.

Baoan Temple

Joey Ho (何良正), a retired dentist, began giving tours 15 years ago in Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese).

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

“Then I switched to Mandarin and then to English, which I learned myself,” he said, adding that he’s been giving English-language tours for a decade. In response to my surprise that he learned English for the purposes of giving the tours, Ho said he did the same with Japanese.

Why expend so much effort on becoming a volunteer tour guide?

“In the past we didn’t learn about Taiwan’s history, geography or local culture because we were ruled by foreign regimes. When the Japanese came, they gave us a Japanese education. When the Chinese came, they gave us a Chinese education. Nothing about Taiwan,” he said.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

This was a theme that Ho, who said his ancestors moved to Taiwan from Guangzhou, China, 220 years ago, returned to throughout the two-hour tour — though spoken without a hint of animosity toward the “foreign regimes.”

Baoan Temple’s presiding deity, Baoshengdadi (保生大帝, also known as the God of Medicine), is the stuff of legend. Originally a Chinese doctor, scholar and exorcist surnamed Wu (吳), he was deified after his death because of his celebrated powers of healing. His resume includes curing a dragon’s eye and removing a hairpin from a tiger’s throat.

But Wu also provided earthly assistance as well. “The God of Medicine protects our life … and protects against diseases such as cholera, malaria and bubonic plague,” Ho said.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

According to an abbreviated temple history, “a rather shabby wooden structure” was initially erected in 1742 by immigrants from Tongan (同安) in China’s Fujian Province. It was made more permanent in 1760 when a larger, more substantial temple was built.

At the same time, a small community — today known as the 44 shops (四 十 四坎) — sprang up around the temple in what is today called Dalongdong. Believing the God of Medicine to be auspicious, merchants as well as others from the surrounding area pooled their money and expanded the temple between 1805 and 1830. Ho showed me two 200-year-old stone lions, one female and one male, guarding the temple’s main gate, in front of which are two stone-carved dragon pillars.

“The female dragon has its mouth closed because in the old days women weren’t allowed to open their mouths,” Ho quipped.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

(The lioness’ mouth was kept open, a taboo that, according to Ho, resulted in a cut in pay for the craftsman who carved it.)

Dragons feature prominently throughout the temple and serve variously as symbols of auspiciousness, luck, protection and, in the case of the dragon with a grass tail, greed. There are heaven dragons (天龍), symbolizing the regenerative power of heaven, and sea dragons (海龍) that benevolently rule the ocean. And though dragons are often a Taoist symbol, Ho said Baoan Temple, like many temples in Taiwan, also features Buddhist and Confucian iconography.

One bas-relief stone carving depicts the qilin (麒麟), an auspicious and mythical creature that is said to have appeared to Confucius’ mother when she was pregnant with the sage. To the left is a mural with several Buddhist swastikas, symbolizing eternity.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

Ho directed my attention to two intricate woodcarvings running parallel to each other above the main gate, made as part of a competition held when the temple was restored between 1917 and 1919.

On one side a bamboo scroll opens up to reveal several figures from Chinese history and mythology, carved by sculptor Chen Ying-pin (陳應彬). The other carving, sculpted by Kuo Ta (郭塔), depicts similar characters but with the addition of Greek pediments and Roman-style verandas.

“Japan was deeply influenced by Europeans and that’s why you can see the Western architectural vocabulary,” Ho said.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

He said the beam carved by Chen won the competition because “at the time the Taiwanese weren’t really friendly to Westerners, which of course had an impact on the selection of the winner.”

To underline his point, Ho took me to the entrance of the temple’s main hall to show me four potbellied characters carved to look like they are supporting the roof beams.

“It means the Western stupid barbarian is holding up the timber,” Ho said. “We didn’t like the barbarians back then, so we gave them a hard job.”

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

We proceeded over to a plaque displaying the temple’s benefactors, one of whom was Koo Hsien-jung (辜顯榮), the father of Koo Chen-fu (辜振甫), former chairman of the Straits Exchange Foundation. The plaque follows the Japanese dating system in use in 1915, but the date was removed and replaced with “fourth year of the Republic of China” (民國四年) when the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) took over.

“After the lifting of Martial Law, we changed it back to the original,” he said.

Ho called the period following the arrival of Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) and his army “a very dark era.”

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

“Following the civil war, this temple was occupied by soldiers and their dependents for 18 years,” he said.

He showed me a Koji pottery plate bearing two Republic of China flags positioned above a door.

“We keep it because it’s an important part of the temple’s history,” he said.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

There appeared to be no animosity in Ho’s rendition of these events, though he did have a tendency to emphasize the evil deeds of the KMT over those of the Japanese.

Ho’s tour demonstrated that every detail of Baoan Temple has its own historical and iconographic significance. But one detail he didn’t point out struck me as particularly telling.

In his excitement to illustrate Baoan Temple’s high pedigree, Ho showed me a plaque bestowed on the temple in 2003 after it won honorable mention in UNESCO’s Asia-Pacific Heritage Awards.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

It reads: Dalongdong, Baoan Temple, Taipei, China.

■ Baoan Temple (保安宮), 61 Hami St, Taipei City (台北市哈密街61號). Tours are open to the public, but must be arranged one week in advance. Telephone: (02) 2595-1676.

Taipei Confucius Temple

Though a week’s notice is required to arrange a tour of Baoan Temple, English and Japanese-language guides are available on a walk-in basis on Wednesdays, Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays at the nearby Taipei Confucius Temple.

One obvious difference between Baoan Temple and Taipei Confucius Temple is the grounds on which they are located. The latter is surrounded by much more green space, presumably to promote scholarly contemplation in the manner of the great sage to which the temple is devoted. Additionally, whereas Baoan Temple was built up and renovated over several centuries, Taipei Confucius Temple has been completely rebuilt.

Originally erected in 1879, it was torn down in 1907 by the Japanese to make way for a school. Construction of the second temple began in 1925 at its current location. Wang Yishun (王益順), a famous craftsman from China (also the designer of Longshan Temple, 龍山寺), oversaw its design and construction until funds dried up in the early 1930s.

But Koo Hsien-jung (the same Baoan Temple benefactor) and others collected money from the local gentry and construction began again in 1935 by Taiwanese craftsmen. (Wang had since passed away.) Taipei Confucius Temple was eventually completed, with further stops and starts, on the eve of World War II.

Dressed in a long flowing robe of regal yellow, Cecelia Chen (陳錦華), my guide, looked like a scholar out of a Qing Dynasty painting. And like the literati, Chen had her banter down, delivering her remarks on the symbolism of the temple’s architecture and murals with panache. The tour lasted about 30 minutes.

Chen was proud of the fact that private donors (and not the government) were responsible for the temple’s construction — evidence of “our great learning,” she said.

At Dacheng Hall (大成殿) Chen pointed out a black plaque with gold lettering that read “education without discrimination” (有教無類). It was written by Chiang Kai-shek and echoes Confucius’ belief that education should be available to all.

No statues of gods or deities are to be found anywhere, and there is no writing on the pillars, which is unusual for a temple.

“We have a saying: Don’t flaunt your writing before Confucius,” Chen said.

Taipei Confucius Temple’s architectural style is known as “Fujian” or “southern Chinese style,” and it has the colorful roofs decorated with statues, carvings and murals typical of such temples.

“In Northern China you won’t find such colorful and decorative roofs because of the cold winter weather,” Chen said. “Consequently the roofs there have no particular meaning.”

Chen led me to the Yi Gate (儀門), also known as the Gate of Ceremonies, and showed me a relief made with Koji ceramics. It depicts a martial figure holding a ball in one hand and a flag in the other. When combined, she explained, “flag” (qi, 旗) and “ball” (qiu, 球) in Mandarin sound the same as the word “praying” (qiqiu, 祈求). A second mural shows a similar character, though this time holding a “spear” (ji, 戟) and a “chime stone” (qing, 磬). When the terms are combined, they sound like the word “auspicious” (jiqing, 吉慶).

“When you put the four symbols together it means praying for auspicious happiness (祈求吉慶),” Chen said.

Similar characters or phrases can be found at most Taiwanese temples, though they may use different carvings, paintings and materials.

“The common characteristic that unites them all is that they contain references to good, wealth and happiness,” she said.

Symbols such as these also serve a practical function, Chen said. A wooden crossbeam holding up one section of the Yi Gate is carved in the shape of a pumpkin (symbolizing fertility). Metal brackets, made to look like dragon whiskers, are fixed to the pumpkin and the vertical beam below it.

“The whiskers serve as support for the beams and protect them from being damaged during earthquakes,” Chen said.

■ Taipei Confucius Temple (台北市孔廟), 275 Dalong St, Taipei City (台北市大龍街275號), is open Tuesdays to Saturdays from 8:30am to 9pm and Sundays and national holidays from 8:30am to 5pm. English and Japanese interpreters offer free tours on Wednesdays, Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays from 8:30am to 12pm and 1:30pm to 5:30pm. Tel: (02) 2592-3934. On the Net: www.ct.taipei.gov.tw

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Aug. 25 to Aug. 31 Although Mr. Lin (林) had been married to his Japanese wife for a decade, their union was never legally recognized — and even their daughter was officially deemed illegitimate. During the first half of Japanese rule in Taiwan, only marriages between Japanese men and Taiwanese women were valid, unless the Taiwanese husband formally joined a Japanese household. In 1920, Lin took his frustrations directly to the Ministry of Home Affairs: “Since Japan took possession of Taiwan, we have obeyed the government’s directives and committed ourselves to breaking old Qing-era customs. Yet ... our marriages remain unrecognized,

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

During the Metal Ages, prior to the arrival of the Dutch and Chinese, a great shift took place in indigenous material culture. Glass and agate beads, introduced after 400BC, completely replaced Taiwanese nephrite (jade) as the ornamental materials of choice, anthropologist Liu Jiun-Yu (劉俊昱) of the University of Washington wrote in a 2023 article. He added of the island’s modern indigenous peoples: “They are the descendants of prehistoric Formosans but have no nephrite-using cultures.” Moderns squint at that dynamic era of trade and cultural change through the mutually supporting lenses of later settler-colonialism and imperial power, which treated the indigenous as