“Is it plastic? Is it wood?” A group of 6-year-olds from Osmani Primary School in Tower Hamlets, London, is standing round an abandoned shoebox, and wondering what it’s made of. “No!” cries one of them, finally. “It’s cardboard!” But the eureka moment is fleeting. Seconds later, one of them wants the answer to a more urgent question: “What’s the box doing here?”

And well might he ask. For our shoebox is not nestling on the carpet of a shoe store. Rather, it’s gracing the floor of a gallery within Britain’s most significant collection of contemporary art: the Tate Modern.

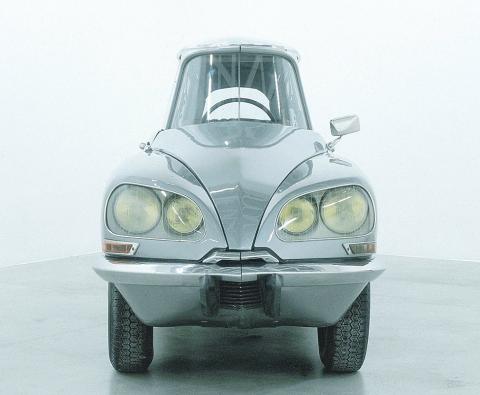

It’s also not just any old empty shoebox. This is Empty Shoe Box (1993), the work of Mexican artist Gabriel Orozco, a sculptor known for his treatment of “found objects.” For the past two weeks, this plain, white box has formed part of the UK’s first full retrospective of Orozco’s career. It is being exhibited alongside a selection of tires; a lift ripped from a Chicago tower block; a knot of four entwined bicycles; a ball of melted inner-tubes; and a vintage Citroen that Orozco has reduced to half its original width.

Photo: AFP

But it’s the box that is attracting all the attention — or none, depending on your point of view.

INTERACTION

Unlike other items on show, the box is not surrounded by “do not touch” signs, or otherwise marked as an artwork. Gallerygoers either don’t see it in time, and kick it over — or they notice it, presume it’s not part of the exhibition, and give it a prod just to make sure. As Jessica Morgan, the exhibition’s curator, tells me: “The box is a confusing thing. It’s intended to make you pause and think about what it might be doing there.”

Photo: Bloomberg

At the Venice Biennale, where the box was first shown in 1993, people reacted by leaving money in it. At New York’s Museum of Modern Art, where it was last shown, the box was apparently often roughly handled. But how is London taking to it? And could an 8-year-old make something better? I spend a day with the box to find out.

Box-watching initially proves uneventful. A lot of people simply don’t notice it, and breeze past. Some clock it vaguely, but — with that weary-yet-unwavering shuffle peculiar to gallery visitors — they drift on, apparently uninterested. In a room that also contains an abandoned lift, a screwed-up car, and a knot of bicycles, perhaps a simple box is unremarkable. Nevertheless, a few do crouch next to it, squint, reassert that, yes, this is a box — and then move on. Some look around frantically for a descriptive placard, eventually finding it on a wall 3m away.

They also then leave immediately, satisfied at this perfunctory explanation.

Photo: Bloomberg

But no one commits an outlandish act such as stamping on the box or wearing it as a hat — and so I ask for anecdotes from the Tate’s various visitor assistants. On the exhibition’s opening day, one tells me, a cleaner thought the box was a bit of rubbish and left it on a pile of debris. “It’s a shame you didn’t come at the weekend,” another assistant says. “It’ll be kicked all over the place.”

But finally, on the stroke of lunch, carnage strikes. Nanna Neudeck, a 27-year-old artist, charges into the box, kicking it several centimeters. She gets a stern ticking-off from an attendant, but claims she didn’t realize the box was part of the exhibition. Only afterwards does Neudeck admit she thought “it might be an artwork.”

But “because the box doesn’t look like art, and because there are no markings around it, then Orozco obviously wants you to interact with it. So I did.”

photo: Bloomberg

The box is soon repositioned but it’s not long before mayhem resumes. In a display of shocking intellectual defiance, two visitors, in two separate incidents, drop morsels of litter into the box. First, a gray-haired man jettisons what appears to be a chewing-gum wrapper. And then, minutes later, a woman in her senior years throws in a scrunched-up tissue.

COLLABORATION

I corner them both, and it emerges that they’re friends: Tony, a former darkroom technician, and Danielle, a retired teacher. They have known each other since the late 1960s, and regularly visit exhibitions together.

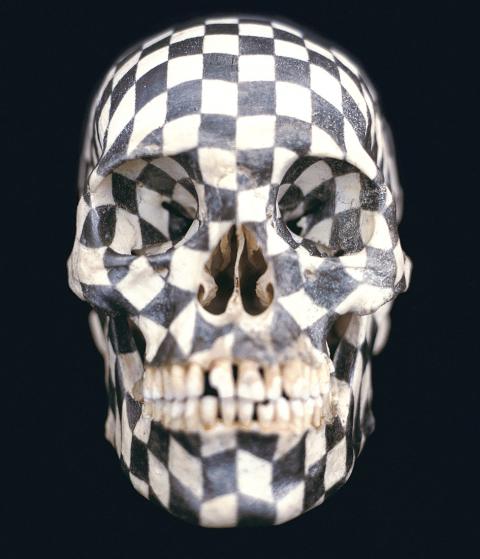

Danielle says their dual-pronged act of litter-loutery constituted a symbolic rejection of what she believes Orozco’s work stands for: the violation of objects. “The car, he’s violated that,” she says. “Those bikes, they can’t move any more, so it’s like he’s killed them. He’s violated all these objects — so I’ve turned his box into a dustbin.”

Danielle’s litter isn’t discovered for 10 minutes — but once it is found, by security guard Jim, the rigmarole that follows is hilarious. Jim informs Martha, the visitor assistant. In turn, Martha calls her manager, and three minutes later, the manager strides in to survey the terrain. She approaches the box. She inspects it — and then leaves, presumably in search of special tissue-extraction utensils. Two minutes later, she returns, armed with rubber gloves. Finally, nine minutes after the litter was first reported, she extracts the offending hanky. For good measure, she also whips out a floor-plan, and checks the box is still positioned at precisely the right angle.

It’s an episode that highlights the most provocative thing about the box: the tension it creates between visitor and gallery. The box attracts attention through its ordinariness, but for the viewer, this ordinariness is not interesting in itself; only the interaction between the box and the gallerygoer that such ordinariness subsequently seems to allow, and even solicit, is interesting. The gallery, however, is less concerned with what the box’s dullness enacts; its primary interest is the dullness itself. The box is on loan to the Tate; as a result, the gallery’s main concern is that the box remains intact, even if this ends up discouraging the interaction that the box was intended to invite.

Morgan argues the box originates from a much simpler idea. Orozco, she says, uses boxes like this one to store his projects in. “So he thought of the box as a thing that contained ideas. And that’s still his perspective on the piece: It’s a shoebox you can fill with ideas.” And it is ideas that those inquisitive 6-year-olds are being encouraged to take from the exhibition. Their teacher Piyara hopes Orozco’s box will show the children that anything can be art — and that they, too, can be artists.

“When it comes to drawing,” she tells the class, “some of you go, ‘Oh, I can’t draw, my drawing doesn’t look very nice.’ But that’s not the point of the drawing — it’s meant to be about you. Look at that box. Some of you might not like it — but that comes from the artist. That’s what he wanted.”

Before the recall election drowned out other news, CNN last month became the latest in a long line of media organs to report on abuses of migrant workers in Taiwan’s fishing fleet. After a brief flare of interest, the news media moved on. The migrant worker issues, however, did not. CNN’s stinging title, “Taiwan is held up as a bastion of liberal values. But migrant workers report abuse, injury and death in its fishing industry,” was widely quoted, including by the Fisheries Agency in its response. It obviously hurt. The Fisheries Agency was not slow to convey a classic government

It was on his honeymoon in Kuala Lumpur, looking out of his hotel window at the silvery points of the world’s tallest twin skyscrapers, that Frank decided it was time to become taller. He had recently confessed to his new wife how much his height had bothered him since he was a teenager. As a man dedicated to self-improvement, Frank wanted to take action. He picked up the phone, called a clinic in Turkey that specializes in leg lengthening surgery — and made a booking. “I had a lot of second thoughts — at the end of the day, someone’s going

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

It turns out many Americans aren’t great at identifying which personal decisions contribute most to climate change. A study recently published by the National Academy of Sciences found that when asked to rank actions, such as swapping a car that uses gasoline for an electric one, carpooling or reducing food waste, participants weren’t very accurate when assessing how much those actions contributed to climate change, which is caused mostly by the release of greenhouse gases that happen when fuels like gasoline, oil and coal are burned. “People over-assign impact to actually pretty low-impact actions such as recycling, and underestimate the actual carbon