On a wall-mounted screen, Marilyn Monroe sings a chorus from Gentlemen Prefer Blondes next to a blown-up photograph of Kristin Scott Thomas pulling off a peroxide wig to reveal the dark hair beneath.

Brunette/Blonde?, which opened this month at the Paris cinematheque, uses film and television archives, photography and art to retrace how generations of movie makers have used women’s hair to seduce and shape their times.

Penelope Cruz stares out from underneath a platinum wig, her sultry Latin looks camouflaged for the camera, for the poster of the show.

photo: AFP

“Women’s hair is a constant motif for all filmmakers, in all films,” said curator Alain Bergala, whether curled and glamorous like Veronica Lake, wild and loose like Brigitte Bardot, or cropped and rebellious like Jean Seberg.

Above all, he said, “the 20th century was the century of blonde imperialism” — and nowhere more so than on the film sets of Hollywood.

Illustrating the point: A pre-war US archive clip of Lana Turner gives women detailed tips on how to achieve the same hairstyle, with short blonde curls wound cherub-like around her head.

photo: AFP

In another, Jane Fonda talks on camera about her early experience of the film industry — how it judged her too dark to be “commercial,” so that for 10 years she was forced to dye her hair and lashes blonde.

A kaleidoscope of Elle magazine covers shows Catherine Deneuve through the ages, polished, thick locks at shoulder length in the 1960s to frizzy-haired blonde in the 1980s — each time a model of femininity for her generation.

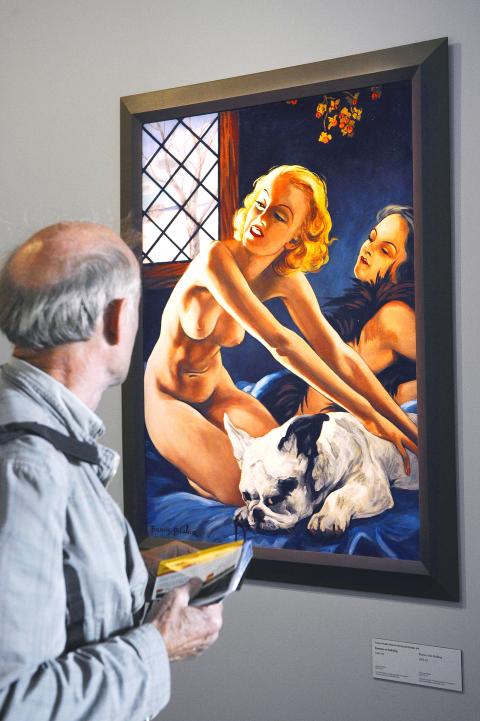

But even in the movie world, the image of the blonde flickered back and forth between “pure and impure.”

Until the 1930s, the blonde was the demure housewife, and the brunette was cast as a temptress. Then the tables turned — the blonde taking over as femme fatale, an enduring myth that culminated in the figure of Marilyn Monroe.

“At each period, the viewer knows how to tell the good girl from the bad, even if the codes have changed,” Bergala said.

Later, the show moves the viewer away from the stereotype of the eternal rivals on to the 1990s and the cinema of David Lynch and his “idea that there is a blonde and a brunette inside every woman,” Bergala said.

In Lynch’s Lost Highway, Patricia Arquette plays both sides of a female figure — dark and blonde. In Mulholland Drive the twin heroines, blonde and dark, are caught in a complex play on identity.

The Paris show also looks at the politics of hair throughout the decades. From the 19th century Suffragettes or 1920s flappers to Jean Seberg’s now-classic crop in the 1960s, short hair symbolized women’s liberation, while Black Panther activists adopted the Afro as a means of protest.

One gem — a US propaganda film from World War II — enjoins women to ditch Veronica Lake-style locks for shorter, practical styles better suited to working on factory machines in the war effort.

On a darker note, the show also highlights how the Nordic cult of blondness was adopted by Nazi Germany as a symbol of racial purity, spreading to Josef’s Stalin’s Soviet Union, which celebrated the ideal of the blonde peasant — and on to the film studios of the US.

The Western myth excluded blacks, hispanics and ethnic minorities, but the show makes a point of touching on hair’s role in other cultures — from Japan to the Middle East, Africa or India.

“In Indian cinema, when two characters fall in love they cannot be shown kissing, so they convey emotion by showing the woman’s hair lifting in the breeze,” the curator said.

Bergala commissioned six filmmakers from around the world to produce short films for the exhibit, including one by Iran’s Abbas Kiarostami that closes the visit.

In the film, four-year-old Rebecca stares straight into the camera, all smiles with her chubby pink cheeks, bright green eyes and long chestnut plait.

But when told her lovely locks might have to be snipped off for the purpose of the plot, she falters, chin wavering and little face dropping as she understands the decision facing her.

It takes a few moments but Rebecca’s choice is clear: Forget making me a movie star — I’m keeping my hair.

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

It was on his honeymoon in Kuala Lumpur, looking out of his hotel window at the silvery points of the world’s tallest twin skyscrapers, that Frank decided it was time to become taller. He had recently confessed to his new wife how much his height had bothered him since he was a teenager. As a man dedicated to self-improvement, Frank wanted to take action. He picked up the phone, called a clinic in Turkey that specializes in leg lengthening surgery — and made a booking. “I had a lot of second thoughts — at the end of the day, someone’s going

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Standing on top of a small mountain, Kim Seung-ho gazes out over an expanse of paddy fields glowing in their autumn gold, the ripening grains swaying gently in the wind. In the distance, North Korea stretches beyond the horizon. “It’s so peaceful,” says the director of the DMZ Ecology Research Institute. “Over there, it used to be an artillery range, but since they stopped firing, the nature has become so beautiful.” The land before him is the demilitarized zone, or DMZ, a strip of land that runs across the Korean peninsula, dividing North and South Korea roughly along the 38th parallel north. This