“Sing-song girls” was the name for high-class call girls in imperial China, on the grounds that they once provided only musical entertainment (though many, not surprisingly, question this assumption about their actual original role). And The Sing-song Girls of Shanghai has been described as the greatest novel ever on the world of the Chinese courtesan, one of the greatest 19th-century novels in Chinese, and in Chinese prose fiction second only to The Dream of the Red Chamber.

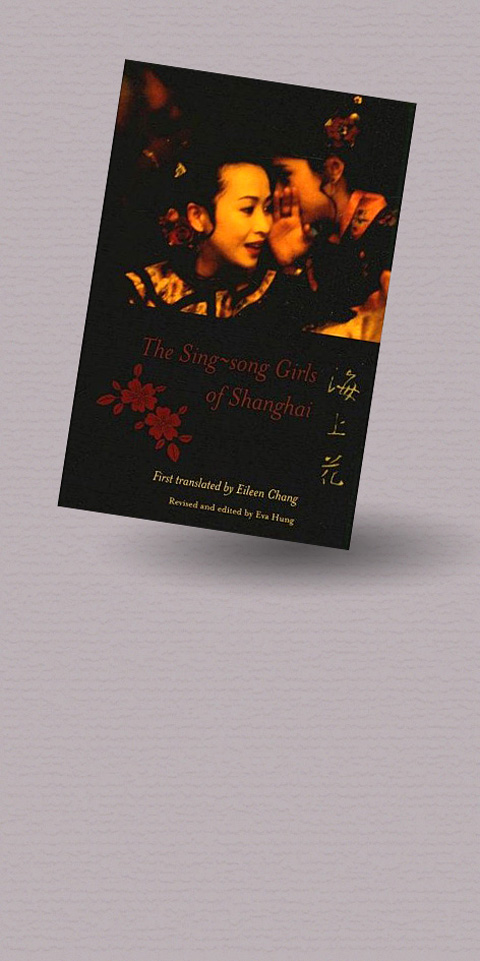

Many celebrated names cluster around this book. First published in 1894, it has been filmed as Flowers of Shanghai, by Taiwan’s Hou Hsiao-hsien (侯孝賢), with the script by Chu Tien-wen (朱天文), author of Notes of a Desolate Man (荒人手記, reviewed in the Taipei Times on March 3, 2003). Eileen Chang (張愛玲), author of the story on which Ang Lee’s (李昂) film Lust, Caution (色,戒) was based, translated it into English, and it’s her translation that forms the basis of this new version. But Chang’s unfinished translation was never published, and was even for a time thought to have been lost. It’s now been edited, probably very extensively, by Hong Kong’s redoubtable Eva Hung (孔慧怡), editor of the long-running journal of translation from Chinese, Renditions, and an esteemed author in her own right.

The book’s a sprawling, maze-like network of plots and subplots, with 101 “major” characters (Eva Hung has compiled a detailed catalogue) meeting and partying in 21 brothels and their adjoining alleys. It isn’t only a great book but a huge one as well, reveling, like Don Quixote, in its own inventiveness, and as vigorous as it is detailed. It presents a world where women have at least equal status with men, in the plot if not in the actual society the story is set in.

As a picture of the 19th-century pleasure quarters of Shanghai, it reels with the heady atmosphere of its real-life originals. But it’s more than this, and can be argued to display the variety, ingenuity and multi-facetedness of all forms of human life in its unbridled forms.

This is because once the constraints of family life and bourgeois respectability are lifted, there’s no end to the elaborate network of inter-relationships and trickery that become possible. Life itself blooms, and all the elaborate machinery displayed in traditional stage comedy comes into its own. (When I first encountered such old comedies as a teenager I wondered why, in the English garden suburb I was being brought up in, nothing ever seemed to happen). Thus this book is full of extortionists, blackmailers, con-men, messengers, locked boxes, abductions, hen-pecked husbands, cheating lovers and meddling mothers, as well as a variety of hangers-on, with lots of laughing out loud as well — though the sing-song girls themselves were trained only to smile.

Money is crucial, but so are card games, food, clothes (everything from fancy outfits to dressing gowns), jewelry, furniture, hair-styles, meals, heavy drinking and — especially remarkable today — opium-smoking. There isn’t an intellectual idea in sight — a sure sign of a literary masterpiece in the making.

This is not to say that The Sing-song Girls of Shanghai makes for easy reading. It must have been an unbeatable time-killer in its day — though apparently it didn’t enjoy particularly large sales — but now our attention span has shrunk. We can take on interminable TV series, of which this book is some sort of predecessor, but when it comes to the printed page we prefer brevity to voluminousness, or an inevitably simplified film version. Still, classics are classics, there to show us various pinnacles of how things can be done when someone of huge talent puts his or her mind to it. They serve as benchmarks to be referred to when some newcomer stakes out an over-ambitious claim, to be taken down and browsed in rather than read again from cover to cover.

Han Bangqing’s (韓邦慶) masterpiece is all about sex really. Han was typical of someone marked out for literary greatness, a man who failed his exams so that the usual career in the civil service was denied him. Instead he took to periodical journalism and a life reporting on — and patronizing — the Shanghai brothels. His book resembles Nagai Kafu’s much more concise Rivalry: A Geisha’s Tale (reviewed in the Taipei Times on March 2, 2008), and as authors Han and Kafu were two of a kind. Both were literary journalists through lack of the opportunity to be anything else, and both were fascinated chroniclers of what used to be called “the demimonde,” ie, the prostitution and nightlife subculture frequently visited by the rich and influential, often on a regular basis.

It’s impossible to outline the convoluted plot, though David Der-wei Wong (王德威) makes an attempt in a distinguished Forward. But then this is the kind of book that attracts introductions and appendices — sheer vastness invites attempts to add to its length and size still further. Eileen Chang herself prepared a translator’s note, reprinted here, and Eva Hung adds an absorbing essay on the world of the Shanghai courtesans.

Hung makes a significant point when she writes that what killed off the world depicted here was the new freedom of men to marry who they pleased. Under the older system of arranged marriages the brothels provided virtually the only opportunity for romantic affairs, which is why the puritan Anglo-Saxon perception of such places as dens of unbelievable vice, simply sex for money, is so very wide of the mark.

The publication of this book is a significant event in the upper echelons of Chinese literary study, at least in its sub-field of translation into English. Finally a book that’s been much talked about is now available to an international readership.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she