Though expected, the news last week that Philippe de Montebello would retire as director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art elicited a range of emotions among museumgoers: pride and sadness at the end of a stellar era, and anxiety about the future.

"I was shaky," said Jerry Saltz, the art critic for New York magazine, striking a common note. "Because just at a time when big museums are getting things like new wings so spectacularly wrong, the Met has been getting things close to perfect."

De Montebello is indeed leaving strong, following several recent gallery renovations and a run of well-attended, scholarly, rigorous and critically acclaimed exhibitions. What happens next at the Met has relevance for all major institutions undergoing a generational shift - and all museums in this young century. Here are some themes certain to arise.

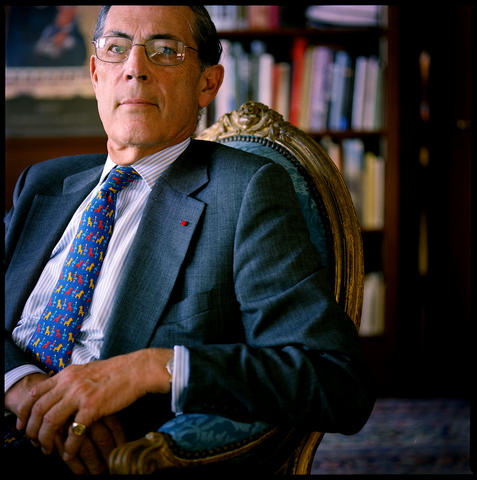

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

THE ART OF THE UNDEAD

A major concern is how the world's leading encyclopedic museum will approach contemporary art. In recent years, the Met has organized scattershot exhibitions by relatively young artists like Neo Rauch and Kara Walker. This past fall, crowds came - and some critics groaned - when the Met put Damien Hirst's shark in formaldehyde on view. Is that a sign of things to come?

"The Met's approach to contemporary art has been extremely erratic and pretty bad, really," said Peter Schjeldahl, the art critic for The New Yorker. But, he added, "I don't see that that should be a priority for that place," especially "in a city full of museums that have that mandate."

Still, as the New York Times art critic Michael Kimmelman put it last week, "so many artists have made the Met their lifelong schoolroom," and their work "would be illuminated next to older art in innumerable ways, not to mention vice versa."

Showing more contemporary art "would be wonderful for Chelsea," said the gallery owner Marianne Boesky, since championing work by relatively new artists would drive up their prices. But is that a good role for the Met? "I'd think very gingerly about placing the Metropolitan's imprimatur on objects," said the gallery owner Richard Feigen. "I'd be very, very covetous of those baptismal certificates."

THE RIGHTFUL OWNERS

In 2006, De Montebello deftly struck a deal with the Italian government to return 21 objects Italy says were looted, in exchange for the long-term loan of other antiquities. But the story isn't going away. In the fall, Yale announced it would return to Peru a group of artifacts excavated from Machu Picchu in 1912. Every so often, new Holocaust art restitution cases emerge.

In a globalized world, where assertions of cultural nationalism are just as politicized as they were when museums first built their collections on expatriated art, restitution claims could be "the biggest trouble" facing the Met's next director, said Peter Plagens, a former art critic for Newsweek.

THE SPACE

Forbidden from expanding further into Central Park, under De Montebello, the Met carved out more exhibition space underground, even under the grand staircase. Unlike every other museum in the world, the Met hasn't embarked on a new wing or an annex for its vast holdings. Will that change? Could it? Should it?

Again, directors and boards don't always see eye to eye. "In the business world, if you don't grow, supposedly you're dying," Perl said. "But I think that's a very dangerous model to impose on the cultural group."

THE POWER OF THE CURATOR

In recent years, the directors of the Museum of Modern Art, Boston Museum of Fine Arts and Brooklyn Museum, among others, have been accused of diminishing the power of their curators. But the Met has remained a bastion of curatorial authority, where curators, not board members or directors, take the lead in conceiving exhibitions based on sound scholarship. "I keep them in line but they keep me in line," De Montebello once said of the Met's 100-plus curators. Will his successor continue that approach?

De Montebello is "the beau ideal of curatorial leadership," said Elizabeth Easton, the director of the Center for Curatorial Leadership. In a news conference last week, De Montebello reasserted his priorities. "Art is first," he said. By contrast, "other institutions have embraced as a primary part of their mission the museum experience, in opposition to the experience of coming to look at a work of art."

De Montebello once referred to the Met as "a great ship that you don't turn around that easily." Maybe so, but things change fast. "If you'd said to people 15 years ago, 'The Guggenheim will become a kind of rental room for Eurotrash and that the Modern will become a museum that's unfriendly to curators,' everyone would have said, 'You're crazy,'" Perl said. Yet both those things have arguably come to pass. "The problem," he said, "is institutional history is not an assurance for the future."

Before the recall election drowned out other news, CNN last month became the latest in a long line of media organs to report on abuses of migrant workers in Taiwan’s fishing fleet. After a brief flare of interest, the news media moved on. The migrant worker issues, however, did not. CNN’s stinging title, “Taiwan is held up as a bastion of liberal values. But migrant workers report abuse, injury and death in its fishing industry,” was widely quoted, including by the Fisheries Agency in its response. It obviously hurt. The Fisheries Agency was not slow to convey a classic government

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

It was on his honeymoon in Kuala Lumpur, looking out of his hotel window at the silvery points of the world’s tallest twin skyscrapers, that Frank decided it was time to become taller. He had recently confessed to his new wife how much his height had bothered him since he was a teenager. As a man dedicated to self-improvement, Frank wanted to take action. He picked up the phone, called a clinic in Turkey that specializes in leg lengthening surgery — and made a booking. “I had a lot of second thoughts — at the end of the day, someone’s going

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party