Mexico's country music stars are being killed at an alarming rate - 13 in the past year-and-a-half, three already in December - in a trend that has gone hand in hand with the surge in violence between drug gangs here.

None of the cases has been solved. All have borne the signs of Mexican underworld executions, sending a chill through the ranks of other grupero musicians, who sing to a country beat about love, violence and drugs in modern Mexico.

One of the most shocking attacks came when Sergio Gomez, the founder and lead singer of K-Paz de la Sierra, was kidnapped while leaving a concert in his home state of Michoacan early on Sunday morning, Dec. 9.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

His body was found the next day dumped on a roadside outside this city, the state capital. He had been beaten, tortured with a cigarette lighter, then strangled with a plastic cord, officials said. He was 34 and had just been nominated for a Grammy Award.

"We don't understand why this happened," his uncle, Froylan Gomez, said in an interview. "He never did anyone any harm."

The motives for the killings remain a matter of speculation, and no evidence has been found to link them to a single killer. In some cases, the musicians appeared to have ties to organized crime figures, making them potential targets in reprisal attacks from rival gangs.

Others had composed songs known as narcocorridos, ballads glorifying the shadow world of drug dealers and hit men, which sometimes offend other drug dealers and hit men. In still other cases, as the musicians' fame grew, they seemed to have become embroiled with criminals unwittingly.

"Sometimes there is a direct relationship between the musician and the narcotics trafficker," Miguel Olmos, a musicologist at the College of the Northern Border in Tijuana, said. "But also there are a lot of passionate crimes. That is to say, the musician establishes some sort of sentimental relationship with people who are linked to this culture of violence and of narcotics trafficking and somehow it gets out of hand. They always touch some nerve of the trafficker."

In the case of Gomez, who was best known for his stirring love songs, prosecutors are investigating whether he had ties to organized crime. So far, however, the investigation into his abduction has been a morass of conflicting accounts, missing witnesses and loose ends unlikely to be tied up soon.

Investigators have yet to interview the two music industry impresarios with Gomez when he was kidnapped, nor have they interviewed the other members of his group. "We hope we can locate all these people," said Maria Elena Cornejo Chavez, the assistant attorney general of Michoacan state. "It's very complicated for us because they all left the state."

The killings have been particularly brutal. On Dec. 13, Jose Luis Aquino, 33, a trumpet player with Los Conde, was found beaten to death in Oaxaca state, with a plastic bag over his head and his hands and feet tied.

On Dec. 1, Zayda Pena, the raven-haired lead singer of Zayda y los Culpables, was shot in a motel room in Matamoros in Tamaulipas state. She survived the attack, but the killers followed her to the hospital and finished her off with two more bullets as she lay in bed. She was 28.

"We are in shock, because it's a weird thing that in one week three members of the grupero wave would be killed," Jose Angel Medina, the leader of the group Patrulla 81, said to reporters after the recent killings. "We are afraid because we are superexposed and this could keep going. We don't know who's next."

Entire groups have been targeted as well. Four members of Los Padrinos de la Sierra were shot and killed in Durango state on June 9. On Feb. 19, assassins with machine guns attacked the members of Tecno Banda Fugaz in the town of Puruaran, Michoacan, killing four and wounding one.

The toll in 2006 was equally grim. On Aug. 9, three members of Explosion Nortena, a group who dedicated themselves to songs about drug traffickers, were shot and seriously wounded in their offices in Tijuana, across the border from San Diego.

Nov. 25 of that year brought the assassination of the singer Valentin Elizalde, 25, along with his manager and driver, shortly after a show in the border town of Reynosa, Tamaulipas, across from McAllen, Texas. More than 66 rounds from an AK-47 were fired into their car.

A month later, Javier Moralez Gomez, a member of Los Implacables del Norte, was shot to death in Huetamo, Michoacan.

All the victims played various genres of Mexican country music, distinguished by its oompah beat and emotional lyrics about everything from unrequited love to famous bandits.

Some were known particularly for their narcocorridos. One of Pena's hits, for instance, was Tiro de Gracia, a reference to gangland executions. Elizalde was also well known for his ballads about bandits and drug kingpins.

Gomez, of K-Paz de la Sierra, however, was different. His biggest hits were love songs like Mi Credo (My Creed) and Volvere (I Will Return.) His band played in the Durango dance style, characterized by the prominence of brass instruments and a superfast, march beat. Like many other grupero combos, the band members wore identical western suits and cowboy hats.

News of his death prompted some musicians to cancel concerts in Michoacan. Others said the killings made them nervous about appearing in public.

"These assassinations have been done with a lot of cruelty and this makes us tense," said Jorge Medina, a singer with La Arrolladora Banda, in a televised interview.

Michoacan investigators say Gomez left a stadium in Morelia after his concert at about 3:30am on a Sunday morning. He was in the company of a driver and two music industry executives, Javier Rivera and Victor Hugo Sanchez. They drove off in a sedan, the police said. The other seven musicians in the band and two of Gomez's brothers followed in other cars.

A short while later, a member of the group called the federal police and reported that Gomez and the two businessmen had been abducted by armed men about 5km outside Morelia on the highway to Salamanca. The federal police informed the state police, the authorities said.

What happened next remains unclear. The state police maintain that when they arrived at the scene, federal agents told them they had interviewed the two businessmen and determined the kidnapping had been a false alarm, said Cornejo, the deputy state attorney general. A spokesman for the federal attorney's office in Morelia, Miguel Angel Hernandez, confirmed this account.

Yet Gomez was tortured to death between 4:30am and 11am Sunday in an unknown place, an autopsy found. He had been beaten badly around the head and chest. His thighs and genitals had been burned. He died of strangulation.

In Ciudad Hidalgo, a small farming town nestled in a valley about 100km east of Morelia, people remembered Gomez with warmth. He had grown up there, the son of a local singer who had never made the big time, in a modest house in a poor neighborhood. While still a teenager, he married a girl from a nearby ranch, lived in his parent's home, fathered his first child and went to work as a cabinetmaker.

The entire family moved to Chicago during the financial crisis in the mid-1990s, where Gomez worked menial jobs, fathered two more children and ran into trouble with immigration authorities. Eventually he found work as a sound technician for a band, Montez de Durango.

In 2003, he and three musicians from that group formed K-Paz de la Sierra. His career took off. The band recorded four highly successful albums and regularly toured arenas and large concert halls venues in Mexico.

He also visited Ciudad Hidalgo every year and gave thousands of US dollars to expand the grade school where he studied as a child. He never put on airs with his old friends, neighbors said. "He always behaved very well," said one acquaintance, who asked not to be identified for fear of drug dealers. "He was not one to be very snobbish."

His wife, Felicita, told reporters he seemed relaxed in the days just before his death and never mentioned any threats. "I never saw him nervous or expecting something bad," she said.

Froylan Gomez noted his nephew never sang about drug dealers or used drugs himself. "This man didn't even smoke or drink," he said. "We cannot understand why it happened. The whole family is demanding justice. We want to know who is the author of this crime."

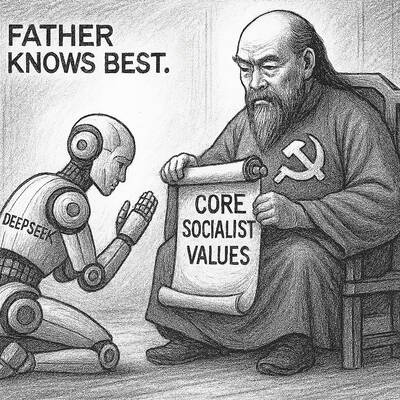

It’s Aug. 8, Father’s Day in Taiwan. I asked a Chinese chatbot a simple question: “How is Father’s Day celebrated in Taiwan and China?” The answer was as ideological as it was unexpected. The AI said Taiwan is “a region” (地區) and “a province of China” (中國的省份). It then adopted the collective pronoun “we” to praise the holiday in the voice of the “Chinese government,” saying Father’s Day aligns with “core socialist values” of the “Chinese nation.” The chatbot was DeepSeek, the fastest growing app ever to reach 100 million users (in seven days!) and one of the world’s most advanced and

Has the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) changed under the leadership of Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌)? In tone and messaging, it obviously has, but this is largely driven by events over the past year. How much is surface noise, and how much is substance? How differently party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) would have handled these events is impossible to determine because the biggest event was Ko’s own arrest on multiple corruption charges and being jailed incommunicado. To understand the similarities and differences that may be evolving in the Huang era, we must first understand Ko’s TPP. ELECTORAL STRATEGY The party’s strategy under Ko was

The latest edition of the Japan-Taiwan Fruit Festival took place in Kaohsiung on July 26 and 27. During the weekend, the dockside in front of the iconic Music Center was full of food stalls, and a stage welcomed performers. After the French-themed festival earlier in the summer, this is another example of Kaohsiung’s efforts to make the city more international. The event was originally initiated by the Japan-Taiwan Exchange Association in 2022. The goal was “to commemorate [the association’s] 50th anniversary and further strengthen the longstanding friendship between Japan and Taiwan,” says Kaohsiung Director-General of International Affairs Chang Yen-ching (張硯卿). “The first two editions

It was Christmas Eve 2024 and 19-year-old Chloe Cheung was lying in bed at home in Leeds when she found out the Chinese authorities had put a bounty on her head. As she scrolled through Instagram looking at festive songs, a stream of messages from old school friends started coming into her phone. Look at the news, they told her. Media outlets across east Asia were reporting that Cheung, who had just finished her A-levels, had been declared a threat to national security by officials in Hong Kong. There was an offer of HK$1m (NT$3.81 million) to anyone who could assist