Every weekday evening, Simon Rogers rides the uptown Number One train from his job in the garment district of Manhattan to his home on the Upper West Side. He usually sits near the door for a good view of people climbing aboard, but on this day Rogers was seated near the center of the car because the train was crowded. Almost automatically, he began evaluating his fellow passengers, and his eyes found an older man in a newsboy cap and glasses.

There was something intangibly compelling about the man, and Rogers weaved his way through the throng of subway riders toward the stranger. As he approached, Rogers, a native of England, leaned in close. In a winsome British accent, he said quietly, "Excuse me, sir. I own a talent agency and I think you'd be good for it. There's something unique about you."

Rogers, who specializes in so-called real-people models, fished out a business card emblazoned with the name Ugly New York and handed it to his catch, who introduced himself as Russell Avery.

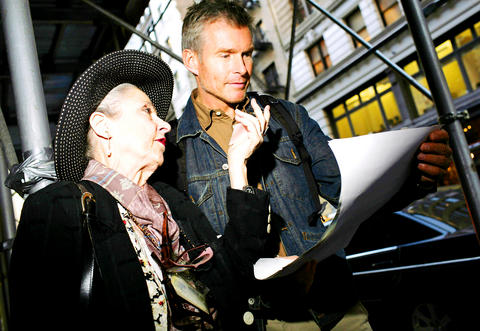

PHOTOS: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Before Avery could get the wrong idea, Rogers quickly added: "We have all kinds at my agency. All shapes, all sizes. Tall, short, fat, thin. Great-looking people, people who've really been hit with the ugly stick, and everything in between. If you're interested at all, there's a Web site at the bottom that you can check out and give us a call."

Rogers opened his agency, an affiliate of an established agency in London called Ugly Models, last summer, becoming one of the dozens of talent and scouting agencies that have either opened or reconfigured their business in recent years to specialize in "models that don't look like models."

This type of model has become the advertising industry's answer to the quest for authenticity. The working theory is the belief that Americans like imagining that living rooms of yore looked like something from a Restoration Hardware catalog. And that the model who looks like the suave but approachable neighbor down the street is not only more credible, but more easily emulated. (I could be that guy - all I need is his after-shave.)

SOMEONE TO RELATE TO

Using these models in ads is not a new trick on Madison Avenue - remember the cowboys who became Marlboro men? But right now just might be a golden age for average Joes and Janes. They have been popular in advertising campaigns for electronics (Apple, Sony and Hewlett-Packard), skin care (Dove) and even some luxury brands (Chanel).

Peter Arnell, the founder of the Arnell Group, a brand and product invention company, said the trend toward using real-people models had grown notably in the last five years thanks to reality television, YouTube and MySpace. "It's an American Idol world," Arnell said. " And when global brands like Apple choose to use the familiar and to give opportunities to unknown people, you know it's hit mainstream."

Sean Patterson, the president of Wilhelmina Models, said that his agency had a 10-year-old division that represented the models who did non-fashion advertising, which he said made up the bulk of the advertising business.

Revenues for that segment are up 30 percent this year, he said, attesting to the demand for relatable faces. (Unlike the models at agencies like Ugly New York, the non-fashion talent at Wilhelmina doesn't come in various shapes and degrees of comeliness; the models still tend to be thin and photogenic, Patterson said.)

But from a model scout's perspective, what is real? What makes one crooked nose flawed and another endearing?

Street scouts tend to fixate on individuals with an unusual look and an easy confidence. Rogers, for example, says he picked Avery because "he looked so chipper, well put together, and somehow vibrant sitting there on the train."

Rogers has found new talent while working out at the gym; his agency even signed a messenger who came to his office to deliver a package. Rogers and others said they managed their talent's expectations about how often they would work - perhaps never - and charged only minimal fees to cover basic costs. Ugly New York, which Rogers said would be the subject of a reality show next spring on cable television, requires new models to pay US$75 for a stack of "comp cards" to leave with potential clients.

Jennifer Venditti, who founded a casting agency in New York called JV8 Inc a decade ago, tells her scouts to "beware of style but no content." Often, she said, "people create an image through what they wear, but there's nothing to them once they take all that stuff off."

As an example of her process, Venditti recounted a project she worked on with the fashion photographer Bruce Weber, who was shooting Kate Moss for W magazine. Venditti, who had to find real-people models to populate the background, dropped in on a high school prom in Detroit. "Suddenly I saw the most amazing person," she recalled, her voice becoming nearly rapturous. "This incredible sculpted face, long hair, wearing a tuxedo.

"She just made me want to look," said Venditti, and the girl ended up in the shoot.

Camille Adams, a former model and fashion stylist, started a real-people talent agency called Menagerie Models in St Louis last year after noticing that photographers she worked with were moving away from professional models. What she is looking for in a real model, she said, is essentially archetypal.

THE RIGHT STUFF TO STRUT

"You'd have to look at them and say, 'That's a banker by their glasses or the suit they're wearing,'" she said. "This morning, I was crossing the street and there was an Asian girl with a hat on." She looked like a student, Adams said. "She was wearing a peacoat and jeans and she was carrying a bag. But it was in her face. She had a serious look, and she was walking with some determination."

In some instances, scouts are casting little scripts. "A client wanted a woman in her 30s who looked like she might own a clothing boutique," said Susette Blackwell of the Blackwell Files, an agency in San Francisco that has specialized in real people for years. In addition to going to actual clothing stores, Blackwell searched the streets for "appealing, artsy women who were stylish, had a nice complexion and a look of quiet confidence."

There is also a clear incentive to using real people, who typically will be paid anywhere from a third to half what a professional model would. Rogers said that the talent signed to the nonunion side of his agency was paid anything from "zero dollars" for first-time appearances to US$7,000 a day for print ads.

A spokeswoman said the use of ordinary people in Dove's Campaign for Real Beauty, which began in 2004, is not based on cost considerations. "It's never been something that's come up," said Kathy O'Brien, the marketing director for Dove, a Unilever brand. "These campaigns adhere to our overall mission. Most recently, we've committed ourselves to building self-esteem among young girls."

But in the end, some say, the shift to real-people models is just another marketing ploy. After all, real people can also mean really unusual people. Rogers, for instance, represents a buxom burlesque performer, a 367kg Sumo wrestler and a man with a green beard named Miss Colombia.

Under pressure, President William Lai (賴清德) has enacted his first cabinet reshuffle. Whether it will be enough to staunch the bleeding remains to be seen. Cabinet members in the Executive Yuan almost always end up as sacrificial lambs, especially those appointed early in a president’s term. When presidents are under pressure, the cabinet is reshuffled. This is not unique to any party or president; this is the custom. This is the case in many democracies, especially parliamentary ones. In Taiwan, constitutionally the president presides over the heads of the five branches of government, each of which is confusingly translated as “president”

Sept. 1 to Sept. 7 In 1899, Kozaburo Hirai became the first documented Japanese to wed a Taiwanese under colonial rule. The soldier was partly motivated by the government’s policy of assimilating the Taiwanese population through intermarriage. While his friends and family disapproved and even mocked him, the marriage endured. By 1930, when his story appeared in Tales of Virtuous Deeds in Taiwan, Hirai had settled in his wife’s rural Changhua hometown, farming the land and integrating into local society. Similarly, Aiko Fujii, who married into the prominent Wufeng Lin Family (霧峰林家) in 1927, quickly learned Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) and

The low voter turnout for the referendum on Aug. 23 shows that many Taiwanese are apathetic about nuclear energy, but there are long-term energy stakes involved that the public needs to grasp Taiwan faces an energy trilemma: soaring AI-driven demand, pressure to cut carbon and reliance on fragile fuel imports. But the nuclear referendum on Aug. 23 showed how little this registered with voters, many of whom neither see the long game nor grasp the stakes. Volunteer referendum worker Vivian Chen (陳薇安) put it bluntly: “I’ve seen many people asking what they’re voting for when they arrive to vote. They cast their vote without even doing any research.” Imagine Taiwanese voters invited to a poker table. The bet looked simple — yes or no — yet most never showed. More than two-thirds of those

In the run-up to the referendum on re-opening Pingtung County’s Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant last month, the media inundated us with explainers. A favorite factoid of the international media, endlessly recycled, was that Taiwan has no energy reserves for a blockade, thus necessitating re-opening the nuclear plants. As presented by the Chinese-language CommonWealth Magazine, it runs: “According to the US Department of Commerce International Trade Administration, 97.73 percent of Taiwan’s energy is imported, and estimates are that Taiwan has only 11 days of reserves available in the event of a blockade.” This factoid is not an outright lie — that