Inside the rock-hewn Medhane Alem Church, in the remote mountain town of Lalibela, the late-afternoon Mass was drawing to a conclusion. Barely visible through the cavernous gloom, hundreds of white-muslin-wrapped worshipers huddled beside pillars and prostrated themselves on small rugs, kissing the cold stone floor. In the sanctuary, priests and deacons gathered around tattered Bibles written in Geez, the 2,500-year-old language still used in Ethiopian ritual, chanting prayers that echoed through the vaulted chamber.

Then the faithful turned as one toward the east, in the direction of Jerusalem. Secreted in an alcove behind a scarlet curtain, forbidden from view to all but a select group of priests and monks, lay a golden cross belonging to the revered King Lalibela, and a replica of the Holy Ark, the wooden box encased in gold that supposedly contained the tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments.

I had arrived in Lalibela, fortuitously, just before the Feast of the Transfiguration, Aug. 6, a key date in the Orthodox Christian calendar that commemorates Jesus’ appearance in divine form before three of his apostles on Mount Tabor. Within a few minutes, my guide had whisked me to the grandest of King Lalibela’s 11 monolithic churches, chiseled out of a single mass of reddish limestone by royal craftsmen at the end of the 11th and the beginning of the 12th centuries.

PHOTOS: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

The churches of Lalibela, a dirt-poor mountain village that has remained essentially unchanged for a millennium, constitute the most remarkable part of what Ethiopians call “the historic tour” — a several-day circuit through ancient Christian kingdoms that flourished in the northern highlands beginning in the fourth century AD. According to legend, Syrian monks crossed the Red Sea then and converted the Aksumite king, Ezana, from paganism to Christianity. Over the following centuries, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church spread throughout the country.

Today, it is widely believed that about half of Ethiopia’s 70 million people are Orthodox Christians (though some experts contend that Islam is now the predominant religion). In the northernmost province of Tigray, where the Orthodox religion took root, 3,500 churches cover the landscape, and the practice of Orthodoxy is nearly universal.

the road from conflict to peace

For decades, however, access to the historic sites, and to Ethiopia in general, has been subject to the vagaries of politics and war. In the 1970s and 1980s, the Soviet-backed Marxist dictatorship known as the Dergue, led by Haile Mengistu Mariam, sealed itself off from the West, while torturing and murdering tens of thousands of opponents and presiding over the catastrophic 1984 famine in which one million people died.

After months of fierce fighting, a coalition of rebel forces overthrew President Mengistu in 1991. (He fled into exile in Zimbabwe.)

Over the next seven years, foreigners — mostly humanitarian aid workers, diplomats, journalists and hardy backpackers — trickled into Ethiopia. I visited the country during this period, when I was based in Nairobi as a correspondent, and it was a rewarding but rough experience.

The door slammed shut in 1998, when a territorial dispute between Ethiopia and Eritrea erupted in a savage war that lasted for two years. The conflict ended with a peace deal signed in 2000.

In the five relatively calm years since, tourists have returned to Ethiopia. They arrive in a nation that under President Meles Zanawi, the former leader of the guerrilla army that overthrew Mengistu and who has been in power for 15 years, remains one of the poorest countries on earth.

In Ethiopia, the per capita income is US$120 a year; tuberculosis and other contagions are rampant; and the literacy rate is just 43 percent.

But under Zanawi, who has begun to show some dictatorial tendencies of his own, significant development has come to Ethiopia, including mobile phone networks, decent hotels, Internet cafes, reliable electricity, and asphalt roads.

And it is now possible to travel across Ethiopia with some degree of comfort.

Those who want to venture on their own will discover that Ethiopia is reasonably well set up for independent exploring. They will find a proud, if bedraggled country with ruggedly beautiful landscapes and a unique sense of its identity — shaped in part, by Ethiopia’s stubborn refusal to submit to Western colonizers.

I arrived in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s 1.2km-high capital, on a cold, drizzly afternoon early last month, and flew the next morning in a 52-seat Ethiopian Airlines Fokker to Aksum in Tigray. I remembered Tigray, which I had driven through in 1993, as a bone-dry, high-altitude desert, a land of canyons and chronic food shortages. But this time, at the height of the wet season, the plateau was vibrantly green.

“God has blessed us with two years of plenty of rainfall,” I was told by my guide, Sisay Ymer, a 30-year-old former seminarian who greeted me at the airport.

As we rode into town, I could see terraced fields of teff, the Ethiopian staple — a wheat-like crop used to make the spongy Ethiopian bread, njera — extending across the rolling terrain in every direction.

Aksum is a town of about 47,000 that is just beginning to recover from decades of war and political turbulence. Its decrepit appearance belies its rich history. Nearly 3,000 years ago, Aksum emerged as one of the principal cities of the kingdom of Saba, a prosperous commercial state centered in Yemen that controlled the main trading routes between the Red and Mediterranean Seas.

The town’s best-known ruins date to the reign of the first Christian king, Ezana, and his successors: a field of dozens of granite obelisks, between 3m and 27m high, intricately carved with rune-like geometric shapes. This strange and mystical place, a cemetery for aristocrats and monarchs, is honeycombed with crypts.

The grandest of these stelae, 23m high and weighing 145 tonnes, was carted off to Rome by Mussolini’s invading army in 1937. But last year, after a decade of pressure by the Ethiopian government, Italy returned the stolen treasure to Aksum, touching off days of celebrations.

Just across from the field stands the Church of St. Mary of Zion, a vine-shrouded stone structure built in the 1600s. The basilica replaced the original fourth-century church — believed to be sub-Saharan Africa’s oldest — which was burned down by an invading Arab army in the 10th century.

Across from the church is the building known simply as the Treasury, whose nondescript appearance hides its key role in Ethiopian Judaeo-Christian mythology. Many Ethiopian believers insist that the building houses the original Ark of the Covenant — the gold-leafed wooden box encasing the actual stone tablets delivered by God to Moses on Mount Sinai.

Menelik I, believed by Ethiopian Christians to be the offspring of King Solomon and the Ethiopian Queen of Sheba, is said to have stolen the ark from the First Temple in Jerusalem and brought it to Aksum a thousand years before the birth of Christ.

No one but a single monk is allowed to see the sacred artifact, though replicas, known as tabots, are brought out once a year for the Timkat celebration of Christ’s baptism on Jan. 19.

The most revered Aksumite kings were Kaleb and his son Gabremeskal, who spread Christianity from the royal court through the villages of Ethiopia in the sixth century. My guide, Sisay, who was incongruously clad in a bright red jacket and tie, black slacks and shiny black shoes — his official guide’s uniform — led me on foot up a rutted road to the ruins of Kaleb’s palace, at first glance an unimpressive pile of rubble.

Then we descended a stone staircase into a network of subterranean burial chambers, constructed of huge, finely chiseled blocks of granite, that fit together as neatly as the blocks of a Rubik’s cube.

Entering the musty vault, where the monarchs were originally buried, Sisay illuminated the passageways with a thin candle. Fifteen-hundred-year-old carvings of elephants and distinctive Aksumite crosses — formed by four delicately shaped, not-quite-touching petals — were still clearly visible on the granite walls.

Wandering through the ancient burial chamber had evidently moved Sisay deeply. With his eyes closed, swaying back and forth, candlelight flickering against his face, Sisay chanted the Lord’s Prayer in Geez.

After the hymn, we stepped back in the bright sunlight.

“Can you feel this place’s holiness?” he said. “Ethiopian Christianity was born here.”

The next morning, Sisay woke me early and we set out from my hotel on a hike to the sixth-century Pantaleon Monastery, perched on a hilltop just outside town. King Kaleb spent the last two decades of his life in an ascetic retreat in this monastery, and his bones were eventually interred here.

It was a bright, clear morning: We walked through vibrantly green teff fields, leapt across muddy irrigation ditches, passed the domed Church of St. Michael, built about 10 years ago. We climbed a steep switchback trail hemmed in by cactus-like euphorbia trees.

The monastery, a one-story hut balanced on an outcropping with precipitous drops on all sides, was surrounded by a four-foot-wide ledge that offered panoramic views of the fertile Tigrayan plateau. Sawtoothed mountains rose to the east; to the north, obscured by mist, lay Eritrea.

A wizened, barefoot monk appeared and opened the olive wood door with an iron key, revealing 500-year-old tapestries, and the vault containing the bones of King Kaleb — forbidden to my secular eyes.

Aksum began to decline in the seventh century, and by the 11th century, the Aksum dynasty was gone. In the middle of the 11th century, a new Christian dynasty, the Zagwe, arose in the mountain town of Roha, which later was renamed Lalibela in honor of its most revered king.

According to myth, Lalibela received a vision from angels commanding him to chisel 11 churches out of the soft limestone hills on which the Zagwe capital was built. Over 25 years, master artisans carved both cave churches from vertical cliff faces, and monolithic churches out of bedrock. In 1960, UNESCO declared the churches a protected site, citing “a remarkable coupling of engineering and unique artistic achievement.”

Catching up

Lalibela had modernized since the last time I was there. A paved road, constructed in 1998, ran from a new airport terminal to the town, passing through rugged foothills, with jagged massifs in the distance soaring to 3.7km.

Gone were the nausea-inducing hairpin turns and perilous rock slides that I’d experienced on the old, unpaved road back in 1993. Several hotels have been built, and the main street winding through the town has been paved — or rather, covered by an uneven layer of stones and cement.

But Lalibela, with a population of about 30,000, still has the look of a destitute mountain village: round, thatched-roof mud huts, called tukuls, clinging to steep slopes; peasant farmers wrapped in homespun white cloth robes; goats and sheep that scatter frantically, bleating in distress, before the rare motorized vehicle.

Early the next day, I visited the Church of St. George, named after Ethiopia’s patron saint. Cut in the shape of a perfect cross, it is perhaps the most exquisite of the monolithic structures.

Descending into the encircling trench via a narrow stone staircase, I noticed, in an alcove, a grinning human skull propped atop a jumble of bones. The partly mummified legs and feet reached to the very edge of the crypt.

Deeper in the recess, other skeletons lay prostrate, yellowing skulls, femurs and tibulas intermingled with scraps of clothing. These were remains of five Orthodox Christian pilgrims, Berhane told me, who had trekked to this holy site from Alexandria in the 13th century, and had chosen to be interred in this open-air vault.

“They wanted to spend eternity gazing at the church,” he said. “They didn’t want anything to block the view.”

The next morning, I flew from Lalibela to Gonder, a bustling, ramshackle city of 250,000 in the Amhara-speaking heartland. It served as the center of Ethiopian Christianity from 1635 to 1855, at which point the capital moved to Addis Ababa.

Gonder’s most celebrated monarch, Fasilidas, constructed an elaborate stone castle on the outskirts.

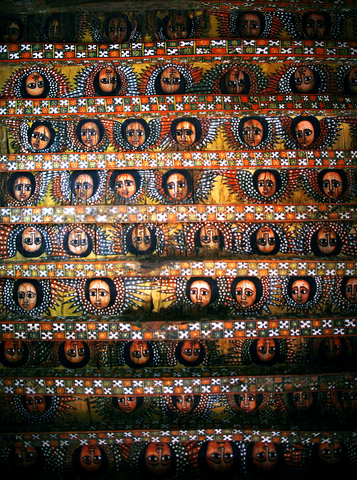

Across town from the castle complex is Gonder’s other main attraction: the Debre Birhan Selassie church, constructed in 1674. A local artist at the time covered the small interior with brightly painted frescoes, recently renovated by UNESCO, that depict scenes of the life of Christ, St. George and the Dragon, Daniel in the lion’s den, the beheading of John the Baptist, and the Devil and the damned. (Unbelievers, demons, and other unsavory types were painted in one-eyed profile.) Hundreds of beatifically smiling angels adorn the ceiling, each one painted with a subtly different expression.

Gonder is also the cradle of traditional Ethiopian music, and I spent my last evening at an intimate bar called Ambasel, drinking beer and listening to a local band — a female singer, a drummer and a masinko player, whose one-stringed instrument is made of goat hide stretched over a box-like frame. Sewbesaw Zebene, my latest guide, translated the vocalist’s Amharic song, a welcome to “the American writer” and a plea to spread the word about Ethiopia.

“Tell the world that Ethiopia is a safe place,” she sang, “The wars are over.”

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

It was on his honeymoon in Kuala Lumpur, looking out of his hotel window at the silvery points of the world’s tallest twin skyscrapers, that Frank decided it was time to become taller. He had recently confessed to his new wife how much his height had bothered him since he was a teenager. As a man dedicated to self-improvement, Frank wanted to take action. He picked up the phone, called a clinic in Turkey that specializes in leg lengthening surgery — and made a booking. “I had a lot of second thoughts — at the end of the day, someone’s going

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Standing on top of a small mountain, Kim Seung-ho gazes out over an expanse of paddy fields glowing in their autumn gold, the ripening grains swaying gently in the wind. In the distance, North Korea stretches beyond the horizon. “It’s so peaceful,” says the director of the DMZ Ecology Research Institute. “Over there, it used to be an artillery range, but since they stopped firing, the nature has become so beautiful.” The land before him is the demilitarized zone, or DMZ, a strip of land that runs across the Korean peninsula, dividing North and South Korea roughly along the 38th parallel north. This