Madagascar, the new computer-animated picture from DreamWorks, is, at least in part, a movie about what a bad idea it is to leave New York City. Its main characters are four residents of the Central Park Zoo -- a zebra, a hippo, a lion and a giraffe -- who abandon their lives of comfortable, pampered confinement and wind up in that strange and confusing place known as "the wild."

Of the four, only Marty, the zebra (voiced by Chris Rock), has any desire to make the trip. On his 10th birthday, in spite of a lovely party thrown by his friends, Marty finds himself in a midlife crisis, and decides to visit the open spaces and grassy savannahs of Connecticut (in whose woods, unbeknownst to him, a leopard once prowled in an older, better movie).

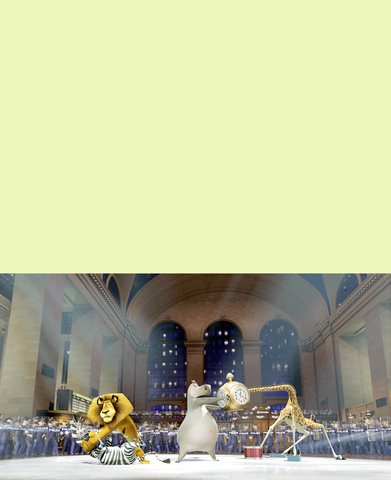

Tagging along with a claque of hard-boiled penguins, who have been re-enacting The Great Escape, Marty lights out for Grand Central Terminal, and his worried pals go after him, arriving at the station by subway in one of the movie's better sequences.

Then, their departure misinterpreted as a result of unhappiness with the zoo, the lot of them are shipped off to a wildlife preserve in Kenya. Instead, by accident, they land on the island that gives the film its title -- a place where, in real life, creatures like them are no more likely to be found than at the Central Park Zoo -- as well as an excuse to fill the screen with adorable, big-eyed lemurs.

The annoying sidekick is a longstanding feature of child-oriented animated entertainment. The chief innovation of Madagascar is that it consists entirely of annoying sidekicks, whose tics and quirks are not quite sufficient to make them interesting characters.

Marty's best pal is the lion, a vain, talkative cat named Alex, who speaks in the rapid-fire, passive-aggressive voice of Ben Stiller. The giraffe, a hypochondriac named Melman, is played by David Schwimmer, and Jada Pinkett Smith is the hippo, a no-nonsense, talk-to-the-hand, big sisterly type named Gloria. Julien, the king of the lemurs (Sacha Baron Cohen, of Da Ali G Show), is perhaps the most annoying character of them all, with his strange, quasi-Caribbean accent and his slinky dance moves, and even he gets a sidekick of his own (Cedric the Entertainer).

Add to this a score by Hans Zimmer, and you may find yourself longing for the quiet and relaxation of a Midtown traffic jam. Like so many other animated features -- Robots is another recent example -- Madagascar spends all its imaginative resources on visual novelty while piecing its story together out of tired conventions and loud, obvious jokes. Some of the New York scenes are both witty and grand, fusing a romantic iconography of Manhattan with incongruous animal movements in a way that makes the city feel both wild and cozy, but once the animals leave town, the movie quickly runs out of ideas.

One advantage to working with talking animals seems to be that they provide an excuse to indulge in scatological humor. Sometimes this is amusing, though the funniest example will surely sail over the heads of younger viewers: "Tom Wolfe is speaking tonight at Lincoln Center," says one sophisticated monkey to another. "Of course we're going to throw poo." On the other hand, I'm not sure why the sight of a giraffe eating a deodorant cake from a urinal is supposed to be funny, unless I'm missing the point, and it's actually supposed to be realistic.

Probably not, since the reality of life in the wild is something that this movie, like others of its kind, treats with anxious timidity. One of the apparent aims of Madagascar is to promote interspecies harmony as a metaphor for multicultural tolerance, a sweet enough idea complicated by the fact that perfectly nice animals often kill and eat one another.

Alex's regression provides the only suggestion of dramatic tension in the movie, which is otherwise smilingly innocuous, with an occasional gesture toward mild naughtiness. It has neither the wit and pathos of Chicken Run nor the emotional sweep and adventurous spirit of Finding Nemo, though it limpingly follows them for a plot point or two.

Instead, it condescends to both its audience -- who it figures will be satisfied with cuteness, flatulence, movie-star voices and bright colors -- and to its characters, about whose lives and aspirations it could hardly care less. Madagascar arouses no sense of wonder, except insofar as you wonder, as you watch it, how so much talent, technical skill and money could add up to so little.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she