It may not be Raiders of the Lost Ark, but Sahara, the screen adaptation of Clive Cussler's sprawling African adventure yarn, is a movie that keeps half a brain in its head while adopting the amused, cocky smirk of the Indiana Jones romps.

A fusion of old and new, it both is and isn't a delirious escape into adventure-serial heaven. Amid its madcap derring-do, the movie inserts clear, simple alarms about environmental protection, African despotism, global interdependence and bureaucratic cowardice.

The movie's dressing up of an old-fashioned adventure fantasy in contemporary threads is an experiment in juxtaposition that gains in assurance as the film bounds along. Given the grim news these days of African nations ground to dust under the boots of ruthless, feuding warlords, the film's caricatured vision of greed, oppression and misery in parts of Africa doesn't feel entirely like a caricature. Ultimate real-life horror, after all, is a grotesque cartoon.

The two-hour-plus film has the timing and stamina of a marathon runner. As Sahara careers between swashbuckling silliness and semi-serious comment, it builds up reserves of energy and good will that pay off when it bursts into its final sprint, a rootin'-tootin' 21-gun finale as satisfying as it is preposterous.

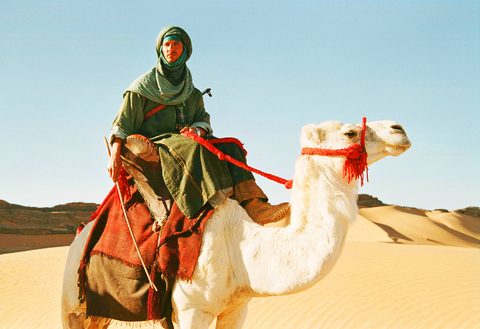

Sahara is the sure-handed directorial debut of Breck Eisner (son of Michael), who maintains strict control of an oversize story (the novel runs to 700 pages) whose multiple plots could easily have splintered into an incomprehensible tangle. The screenplay, credited to four writers, allows you to follow the multinational crew of treasure hunters, warlords, tribal chiefs and officials from various global agencies as they gallivant across Western Africa (the movie was filmed mostly in Morocco) without losing your way.

What starts out as a treasure hunt turns into a desperate attempt to forestall an environmental catastrophe one character calls "the Chernobyl of the Atlantic." Keeping things clear in a movie this capacious isn't easy, as evidenced by the increasing numbers of Hollywood tent poles clad in epic drag that don't make even a token bid for coherence (think only of the Mummy films) and are content to splat themselves onto the screen like reeking pools of regurgitated junk food.

Sahara may be the ultimate test of Matthew McConaughey's still-unrealized potential to enter Hollywood's magic circle. If this movie can't propel the 35-year-old Texan into Harrison Ford's US$20 million trekking boots, nothing can, and the longstanding heir apparent will never be king.

His character, Dirk Pitt, an unflappably game treasure hunter obsessed with finding a Confederate ironclad ship that disappeared at the end of the Civil War and may have landed in Africa, epitomizes Rhett Butler Lite. Twinkling and sinewy, his rakish insolence accented by a mustache, McConaughey's Dirk is the Flower of Southern Manhood, Texan-style, a fearless all-American pirate with a keen sense of humor and a social conscience.

While watching Sahara, I apprec-iated his charming performance, but I also kept asking myself which particular quality on the checklist of essential superstar attributes might explain his inability so far to crack the magic circle and decided it must be his voice. His vocal twang may be a little too high and sharp and inflected with a Woody Harrelson whine for him to convey the unassailable gravitas of a mythic action hero.

In Sahara, the star is romantically matched with Penelope Cruz, playing Eva Rojas, a fearless, fiery-eyed doctor for the WHO. The movie shrewdly avoids forcing the pair to certify their chemistry with phony midaction clinches. That each saves the other's life more than once should speak for itself. Once again, Cruz's fiery physical intensity goes only so far in compensating for her language barrier, but most of her sparse dialogue is watered-down doctor talk.

Dirk meets Eva in Lagos, Nigeria, where he leads a crew salvaging Nigerian relics from a vessel operated by the National Underwater Marine Agency. She is there to investigate the source of a possible plague that may emanate from the Niger River, the same waterway the ironclad ship Dirk that dreams of finding may have traveled two centuries earlier.

When Eva finds evidence that Mali, already torn by civil war, may be the source of the plague, she is menaced by a hooded agent dispatched by that country's reigning warlord. In the nick of time, Dirk comes to the rescue and takes her aboard the marine agency ship. The expedition's French corporate sponsor, Yves Massarde (Lambert Wilson), slowly emerges as the film's conflicted villain, a do-gooder contaminated by greed.

After Eva and her colleagues disobey orders and sneak into Mali, she is again rescued by Dirk and his wisecracking sidekick, Al Giordino (Steve Zahn). The treasure hunt is put on hold while the three intrepid adventurers uncover a toxic-waste nightmare that could escalate into a global catastrophe.

Even with order so strictly imposed, Sahara has more story than it can comfortably accommodate. It brashly, shrewdly pretends otherwise. As it lights out into Indiana Jones territory, it appreciates the African landscapes with an adventurer's discriminating eye.

The transitions between action (an early speedboat battle crackles with wit and energy) and wisecracking banter (McConaughey's Dirk and Zahn's Al, swapping time-honored jokes, make natural sidekicks) are seamless. A robust soundtrack (by Clint Mansell) seasoned with Southern rock 'n' roll and African pop underlines the jaunty mood. It's all sleight of hand, of course, but Sahara lopes into the distance with the easygoing swagger of a con man who has just pulled off a US$100 million scam.

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

It was on his honeymoon in Kuala Lumpur, looking out of his hotel window at the silvery points of the world’s tallest twin skyscrapers, that Frank decided it was time to become taller. He had recently confessed to his new wife how much his height had bothered him since he was a teenager. As a man dedicated to self-improvement, Frank wanted to take action. He picked up the phone, called a clinic in Turkey that specializes in leg lengthening surgery — and made a booking. “I had a lot of second thoughts — at the end of the day, someone’s going

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Standing on top of a small mountain, Kim Seung-ho gazes out over an expanse of paddy fields glowing in their autumn gold, the ripening grains swaying gently in the wind. In the distance, North Korea stretches beyond the horizon. “It’s so peaceful,” says the director of the DMZ Ecology Research Institute. “Over there, it used to be an artillery range, but since they stopped firing, the nature has become so beautiful.” The land before him is the demilitarized zone, or DMZ, a strip of land that runs across the Korean peninsula, dividing North and South Korea roughly along the 38th parallel north. This