In The Jacket, a new time-travel psychological thriller directed by John Maybury, Adrien Brody plays Jack Starks, a soldier in the first Gulf War who miraculously recovers from a bullet wound to the head, after which things get really strange.

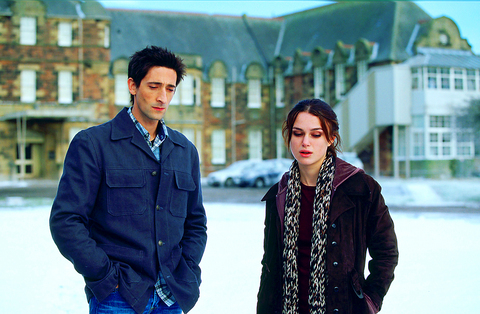

Trudging down a snowy Vermont road, he comes upon a stranded, inebriated woman (Kelly Lynch) and her cute-as-a-button daughter, and repairs their pickup truck. Then, after being set up for a murder that he did not commit, Jack is sent to a gothic state mental hospital, where a sinister doctor (Kris Kristofferson) orders him drugged, restrained (in the garment of the title) and locked in what looks like an oversize filing-cabinet drawer, from which Jack is able to propel himself into the future (approximately two years from now). There, he meets an unhappy waitress played by Keira Knightley, whose British accent has disappeared and whose hair has been dyed brown.

At this point, I will refrain from further plot summary, not because I'm worried about spoiling any surprises, but because to relate plainly and without embellishment what happens in The Jacket would make it sound more preposterous than it is. Make no mistake, this movie is terribly silly, but it's not completely terrible. It starts out trying to be craftily clever -- with lots of fast, disorienting visual effects, echoey music and intimations of politics and paranoia -- and ends up artlessly dumb. In other words, it improves as it goes along.

PHOTO COURTESY OF WARNER INDEPENDENT PICTURES

Maybury, working from a busy screenplay by Massy Tadjedin, shows a fondness for extreme close-ups that is sometimes effective but more often bewildering. For a while, I thought the whole picture was going to be reflected in Brody's eyeballs, and at another point I wondered if the audience was being directed to admire the work of Kristofferson's dentist. In its less hectic moments, though -- scenes in which the camera pulls back far enough to allow Brody and Knightley to occupy the frame together -- the movie achieves a nice mixture of tenderness and foreboding.

What is foreboded is pretty hokey stuff. All of the business about the Gulf War and the intimations of loony-bin political allegory on the model of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest are red herrings, and the movie's premise is overloaded with gimmicks. Because the very idea strains basic canons of logic, time travel requires either extravagance on the order of Back to the Future or elegance, as perfected by Chris Marker in La Jetee in 1962. The Jacket is not the first attempt to update the eerie power of that film, which is composed entirely of still images and lasts less than half an hour, but it joins Terry Gilliam's Twelve Monkeys as a warning to leave well enough alone.

But Brody, stoop-shouldered and wary, remains an engaging presence, and his understatement is soothing in a picture crowded with maniacal overacting. The wonder of it is that Jennifer Jason Leigh, playing a kindly counterpart to Kristofferson's vengeful villain, is not the worst offender. That would be Daniel Craig, as a ranting maniac -- there's one in every ward, at least in the movies -- whose most delusional ravings turn out to be the only things that make sense.

Or maybe not. The Jacket wants to be a clever, puzzling metaphysical whodunit, with a dose of spiritual uplift thrown in for good measure. Since it is too sloppy to work as a brain-teaser like Pi or Memento, the slide into sentimentality comes as something of a relief, even as it leaves behind a tangle of false leads and loose ends.

The motives and methods of the evil doctor, in particular, remain unexplained. His therapeutic practices are, to say the least, unorthodox, but then again, this hospital is a mighty peculiar place. In the day room, for instance, the patients appear to be watching CNN while listening to a lecture by Noam Chomsky, a combination that may explain why they are all twitching and drooling. No wonder Jack is soon begging to be locked up in that drawer, where he can zoom into 2007 and catch a glimpse of Knightley in the bathtub.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a