The chicken is not exactly one of the great animals of legend and literature, and is more often associated with the dinner table than with anything else. But with the beginning of the Year of the Chicken (or Cockerel or Rooster), it is imperative to find something to say about chickens other than the fact that the Mandarin for chicken, "ji" (

Unfortunately, what with all the trouble over avian flu, chickens have not even been a harbinger of good fortune recently. The People's Daily reported that representatives of China's top 100 poultry companies found it necessary last March to gather in the Great Hall of the People to consume a banquet of chicken to prove that the fowl was still all right for the dinner table. Taiwan, which was relatively unaffected, had hopes to make a killing from exporting chicken to Southeast Asia.

But with the rooster crowing in a new dawn, hopefully things will be looking up in 2005 -- both for chickens and for the rest of us.

But the trouble with chickens is that of all the beasts of the Chinese zodiac, they are one of the least exulted. They do not figure much in legend or fable, and for those of us who live in the city, a chicken is something that comes in a polystyrene tray and shrink-wrap, and really has very little to do with feathers, crowing at dawn or even eggs.

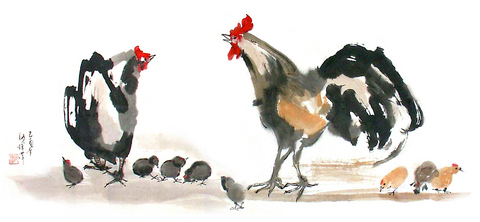

If the chicken can be said to represent anything, it is the homely and the mundane. It is associated with village life, the diurnal routine.

But while scrapping the bottom of the barrel for any kind of hype about the lowly chicken, it has been noted that of the 42,863 poems complied in the Complete Tang Poems (全唐詩), there are 992 that mention chickens. Tu Fu (杜甫), arguably the Tang dynasty's foremost poet, even has a poem entitled The Chicken.

But a quick look at the content of these poems only entrenches the chicken in the mundane world. Typical of references to chickens is the phrase "garlic skins and chicken feathers" (雞毛蒜皮), which refers to trivial, unimportant things, and the earthy phrase about preferring to be "a chicken' s beak rather than a cow's behind" (雞口牛後), which is rather similar to being a big fish in a little pond.

The look of the chicken is open to somewhat wide interpretation, ranging from the cocky preening of the rooster to the loose, sagging skin of the plucked hen. To describe a person has having "chicken skin and crane-like hair" (雞皮鶴髮) is to describe a wrinkled and white-haired old man. But for the sake of those born in the Year of the Chicken, the qualities of the rooster are referred:

People born in the Year of the Chicken usually are good looking and like to show themselves off. Instead of being idle, they always appear to be decent and shrewd in public.

Well, that might be a rooster, but there are also other commentators who suggest that given the endless cycle of ying and yang that rules Chinese cosmology, the Year of the Chicken falls in a ying year. Because of this, there really should be a hen year rather than a rooster year, but then no one really has much to say about hens that is not related to either eggs or the cooking pot.

Looking at the forecast for the next lunar year, it is really not possible to get away from the male imagery. As the Year of the Monkey leads into the Year of the Rooster, there are many indications that troubles will not be easily solved and that overconfidence is going to be a problem for everyone, since both roosters and monkeys are both rather self-regarding creatures. It is a year of hard-line politics and rash business ventures, so it will need all the efforts of more stable zodiac characters to balance things out.

But ultimately, it is the cockerel's crow heralding a new beginning that is probably the most potent symbol for this year. The Tang poet Li He (李賀) said it all when he wrote, "My soul wonders beyond recall, the cockerel's crow brings light of day" (我有迷魂招不得雄雞一聲天下白).

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

It was on his honeymoon in Kuala Lumpur, looking out of his hotel window at the silvery points of the world’s tallest twin skyscrapers, that Frank decided it was time to become taller. He had recently confessed to his new wife how much his height had bothered him since he was a teenager. As a man dedicated to self-improvement, Frank wanted to take action. He picked up the phone, called a clinic in Turkey that specializes in leg lengthening surgery — and made a booking. “I had a lot of second thoughts — at the end of the day, someone’s going

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Standing on top of a small mountain, Kim Seung-ho gazes out over an expanse of paddy fields glowing in their autumn gold, the ripening grains swaying gently in the wind. In the distance, North Korea stretches beyond the horizon. “It’s so peaceful,” says the director of the DMZ Ecology Research Institute. “Over there, it used to be an artillery range, but since they stopped firing, the nature has become so beautiful.” The land before him is the demilitarized zone, or DMZ, a strip of land that runs across the Korean peninsula, dividing North and South Korea roughly along the 38th parallel north. This