This is a love story set in China during the Republican Era (1911 to 1949). The main male character is Virginia Woolf's nephew, Julian Bell, and the main female one based on the Chinese author Ling Shuhua.

Virginia Woolf's sister, Vanessa, married Clive Bell, an art critic. At the age of 27, their son Julian, after trying to make a career for himself as a poet in the Bloomsbury Group, in which his aunt and mother were so prominent, made the decision to go to China. He obtained a job as a lecturer on modern British writing, and arrived in Wuhan in September 1935.

The family had always been unusually open on sexual matters. Vanessa Bell had quite open affairs during her marriage, including one with another art critic, Roger Fry, and her husband did the same. Virginia Woolf at least toyed with lesbianism. Sexual frankness, you might say, was an obligatory part of the Bloomsbury ethos and, brought up in this atmosphere, Julian Bell felt it quite natural to write regularly to his mother reporting on his sex-life.

His letters, which survive, contain details of his affair with a Chinese woman who he indicates by the letter "K." He had been in the habit of attaching letters of the alphabet to his lovers, and this Chinese woman, being the 11th, consequently received the 11th letter. In China during the 1990s, rumor in literary circles had it that this person was Ling Shuhua, a famous writer of short stories and the most eminent woman in the association of modernist writers in 1930s China called the New Moon Society.

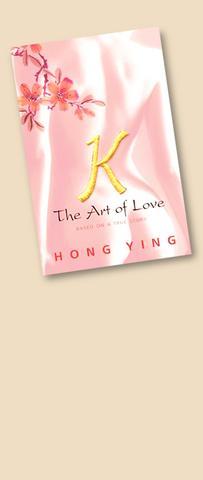

In the summer of 1998, Hong Ying, a young Chinese writer who now divides her time between China and the UK, set about reconstructing this supposed love affair as a novel. It was published in Chinese in Taiwan in 2001 with the title K. In June 2002 Ling Shuhua's daughter, Chen Yiaoying, sued Hong Ying and two periodicals that had published extracts from the novel. Her mother had died in the 1990s, but in China the dead remain protected by libel laws. If found guilty Hong Ying would have had her book banned for 100 years and lost all her assets in China.

But in December last year she was acquitted on appeal. The only condition the court imposed was that certain passages should be cut and the novel's title in China changed to The English Lover. This English paperback edition is presumably of the original complete text, translated by Mark Smith and Hong Ling's husband, Henry Zhao.

The most affluent areas of China during this period are portrayed as a paradise waiting to be destroyed. Wuhan and Beijing are each described in idyllic terms. Julian is given a large house, complete with two servants and a generous salary. The woman he falls in love with, simply called Liu, is the wife of the university's dean and as such she inhabits even more opulent surroundings. As the seasons change over the East Lake, scenic beauties succeed one another in eloquent succession. Beijing, too, is characterized by sumptuous hotels, lavish restaurants and charismatic theaters. Another expatriate calls it "the last paradise."

This enthusiast is Harold Acton, the English ultra-aesthete of the era (he was capable of publishing lines of poetry such as "We groin with lappered morphews of the mind").

One of the great virtues of this novel is that it gets the historical and literary background exactly right. Not only does Hong Ying know all about Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell's circle -- she also knows about the enthusiasm among intellectuals of the era for going to work in China. Another literary personality teaching in Beijing was the brilliant eccentric William Empson -- he continued to sport a wispy Chinese beard into the 1960s. One of the few disappointments of this book is that, though named, he doesn't appear in person.

So, how far does K: The Art of Love deserve its reputation as "the Chinese Lady Chatterley's Lover"? The answer is "to a considerable extent." Julian Bell was a notably liberated spirit, but so, apparently, was "K." The book's subtitle refers to a Chinese classic on sexual techniques and this proves to be her handbook. It was despised by China's modernizers of the time (and its promulgators executed later by the Communists). But to Julian it, and she, were the gateway to an irresistible world of Chinese sexuality. There are some five sex scenes, all explicit (it isn't hard to guess which pages that the court wanted excised in the Chinese edition).

Most extraordinary is the one where K tells Julian she'll take him somewhere he'll never forget. They go to an opium house of exquisite refinement. They undress soon after their first pipe and then a serving girl is called across to assist in their sexual congress, a role with which she turns out to be more than familiar.

Like all the best love stories, this one ends sadly. In the company of a student, Julian sets off into the interior in search of the Reds, who he dreams of joining. What he sees, however, supposedly puts him off revolutions for ever. He nonetheless (and the novel's last chapters are its weakest) finally leaves China to fight in the Spanish Civil War. The real-life Julian Bell was killed near Madrid in July 1937.

This novel is vivid, entertaining, very well-informed and crammed with insights into Chinese life. It's easy to read and once you've started, you'll probably devour it at a sitting.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is