When 28 Days Later is not scaring you silly, it invites you to reflect seriously on the fragility of modern civilization, which has been swept away by a gruesome and highly contagious virus while the hero lies peacefully in a coma. Four weeks after a laboratory full of rage-infected monkeys has been liberated by some tragically misguided animal rights militants, the whole of London -- and possibly every place else -- has been substantially depopulated. The churches and alleyways are littered with corpses and fast-moving, red-eyed "infecteds'' roam the streets looking for prey. Even the rats flee from them and the few healthy humans face a Hobbesian battle for survival.

But what is most striking, and most chilling, about the early scenes of this post-apocalyptic horror show, directed by Danny Boyle and written by Alex Garland, is the eerie, echoing emptiness. Stumbling out of his hospital bed, Jim (Cillian Murphy), a former bike messenger, encounters a familiar metropolis that has been almost entirely stripped of life. Postcard images of the Thames, London Bridge and the dome of St. Paul's Cathedral take on a lurid, funereal glow. After centuries of bustle and enterprise, what remain are vacant buildings, overturned double-decker buses, looted vending machines and cheap souvenir replicas of Big Ben scattered across the sidewalk.

In their previous collaboration, The Beach, Boyle and Garland tried to imagine how a small group of people, removed from the modern world, might reconstitute society from scratch, an experiment whose failure seemed preordained for both the characters and the filmmakers. Here, working with a more solid premise, a smaller budget and greater freedom (and without big movie stars), they probe a similar theme more persuasively.

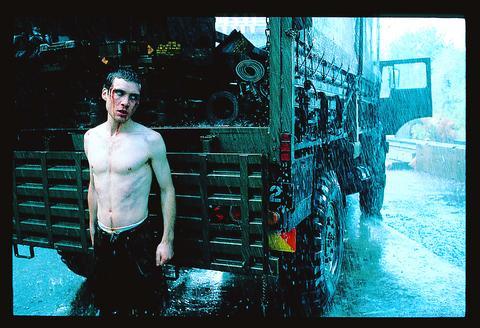

PHOTO COURTESY OF FOX MOVIES

Jim, it turns out, is not entirely alone. Before long, he and some other survivors -- a prickly loner named Selena (Naomie Harris); an affable dad, Frank (Brendan Gleeson); and Frank's adolescent daughter, Hannah (Megan Burns) -- have formed a tiny band of nomads, traveling the English countryside in a big, black taxi and discovering that caring for one another is not just a residue of extinct social norms, but also an expression of the survival instinct.

Other expressions, as you might expect, are not so inspiring. Through the silence comes a radio signal, a voice promising that salvation and the answer to the virus lie with a group of soldiers just north of Manchester. They are led by Major Henry West (Christopher Eccleston), who seems to have graduated from a Lord of the Flies military academy. He and his men are on hand to demonstrate that those who offer protection and security can be even more dangerous than the virus-crazed zombies they keep at bay.

The soldiers also allow Garland and Boyle an exit from nightmarish claustrophobia into a more conventional (though still quite effective) action-and-suspense story. As such, and as a parable of human nature under extreme duress, 28 Days Later is never less than interesting and acknowledges fairly directly its debt to the visionary ghoulishness of George Romero, who made Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead and Day of the Dead. The suggestive juxtaposition of zombification and consumerism in Dawn, which took place mostly in an abandoned shopping mall, is evoked in several scenes here, as are the queasy racial politics of Night.

But the most haunting moments in 28 Days Later have little to do with social allegory, graphic horror or cinematic shock tactics. The movie, shot in digital video by Anthony Dod Mantle (who has worked with Dogma 95 disciples like Harmony Korine, Thomas Vinterberg and Lars von Trier), sometimes has an ethereal, almost painterly beauty. The London skyline takes on the faded, melancholy quality of a Turner watercolor; a field of flowers looks as if it were daubed and scraped directly onto the screen.

Thanks to Mantle's images and Boyle's unexpected restraint, the middle section of the picture, though punctuated by mayhem and grimness, has a pastoral mood, and the actors, unwinding from the stress and panic of London, are allowed to be warm, loose and funny.

Boyle, whose other films include Shallow Grave and Trainspotting, has never been accused of lacking narrative flair or visual style. Rather, he has sometimes been suspected of having too much of both, and of lacking gravity or soul. Those movies, though exciting, could leave a sour aftertaste of cynicism in your mouth.

The content of this one is far more extreme, you can almost smell the rotting flesh. But what lingers is a curious sweetness. Boyle has hardly lost his sly, provocative perversity or his ear for the rhythms of unchecked violence, but he does seem to be maturing. It's as if, in contemplating the annihilation of the human race, he has discovered his inner humanist.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is