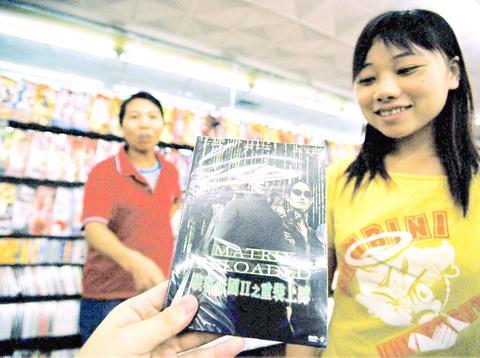

Even before The Matrix Reloaded opened in China's cinemas in July, Liu Ying had watched it twice.

Like many Chinese fans of the popular Matrix science-fiction franchise -- the latest is called "Hacker Empire" in Chinese -- Liu said he watched the movie in his home, on an unauthorized or "pirate" DVD copy.

PHOTO: NY TIMES

The pirated DVD appeared soon after the film's American release earlier this year.

"It wasn't the best copy," he said, "but I've been hanging out for the Matrix sequel. I also figured if I watched it first, it would make more sense when I saw it in a cinema."

Liu, a 23-year-old salesman from this southern Chinese city, is one of millions of Chinese consumers whose appetite for cheap pirated films, music and software is vast and mostly uninhibited.

China's galloping market economy has long run rough and ready over international copyrights. But industry executives and analysts say that in recent years piracy has become even more rampant, aided by the spread of the Internet, and computer technology that allow technology-savvy bootleggers to outrun the government's periodic crackdowns.

A pirate DVD store above a restaurant in downtown Guangzhou makes the extent of such activity abundantly clear. The store, which can be entered only after a telephone call to the proprietor, Li, is two air-conditioned rooms with stacks of thousands of pirated movies.

Besides recent Hollywood blockbusters like Matrix and the latest installment of Harry Potter, there are 1960s French new wave classics, Japanese and Korean romances and gangster films, and gruesome horror and cult films, including Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. The discs sell for US$1 to US$3 each, depending on the quality of the copying technology used.

The customers, most of them college age, pore over titles and line up at Li's counter with several films to watch over the weekend. "Quality is guaranteed," Li says as one customer leaves. "Just knock next time."

Throughout China's cities and towns, mom-and-pop pirate shops like Li's serve a vast and growing market. China has about 20 million DVD players, and by the end of 2006 the number will grow to 42 million, according to David Scott, an analyst with the magazine Screen Digest. China also has 74 million of an earlier generation of disc players that use a less sophisticated form of encoding, a format called VCD.

While some authorized copies of DVDs are available, the Motion Picture Association of America estimates that last year more than 90 percent of the DVDs sold in China were illegal copies.

One reason for the ubiquity of pirated films (and music) is price. Typically, pirated discs sell for a fraction of the price of legitimate discs, while the range of choice among the bootleg versions is much larger.

A regular customer in the pirate stores, Fu Jun, a 24-year-old accountant with a taste for science fiction films, explained that for him and many young Chinese, attending a cinema is a rarer, more expensive experience than buying pirated films and watching them at home with friends.

Price matters

While a DVD player can be bought for less than US$50 and a pirated DVD sells for about US$1, a trip to the cinema can cost US$4 to US$10, he said, adding that the difference means a lot to young people earning only a few hundred dollars a month. "I guess we should consider the legal aspects of piracy," he said, "but students don't have the money."

Buyers of pirated products are almost never punished. The manufacturers and wholesalers of the products can face stringent prison sentences, although this is extremely rare. Small-time sellers can face fines of up to hundreds of dollars. But confiscation is the most common punishment.

American film companies once hoped that the shift from VCD technology to the more heavily encrypted DVD would stem piracy. But bootleggers in China and elsewhere cracked the new technology, and the spread of video technology seemed to make unauthorized copying easier than ever.

"Today's pirates have evolved from backroom operations into technology-driven criminal syndicates organized into business units," said Marta Grutka, a spokeswoman for the Motion Picture Association of America, which has pressed the Chinese government to act more forcefully against video piracy. The syndicates, she said, often steal advance copies of films, or sneak camcorders into advance screenings.

The syndicates find a ready audience in the emerging generation of Chinese who are relatively affluent, technologically sophisticated and hungry for fresh cultural experiences.

Shen Sheng, for example, started his heavily visited Web site, Shooter.com, three years ago as a way of communicating with other Internet-fluent film fans. It began as a site for swapping information about DVD technology and Web broadcasting, he said, but grew into a site where Chinese fans of foreign films can swap subtitles and software for copying films from the Internet.

Now Web sites like his have become hubs for thousands of Chinese film enthusiasts who offer free subtitles and free advice about downloading and copying films.

"Most of my visitors are people on broadband connections who love films; they're mostly into mainstream American films," he said in a telephone interview from his home in Shanghai. "I want to encourage people to freely swap the subtitles they've done themselves."

Pirate subculture

The abundance of pirated films here has also spawned a subculture of Chinese Web sites devoted to discussing the latest releases.

"I often go on the Web to see what's new," said Cherry Ma, a Guangzhou college student who would be identified only by her English name. "You can check out on specialized sites what's out, what the subtitles are like, the packaging." She added that she had not been to a cinema this year.

She and several other devotees of the film Web sites said that the variety of DVD films available in legitimate versions was far more limited than in pirated versions.

"There's growing interest in art films, not just big Hollywood films, especially among educated youth," said Wang He, also a student at a Guangzhou college. "But you just can't buy legitimate copies; there's only pirated versions to turn to."

Much of the work of providing Chinese subtitles is done by college students in Guangzhou and elsewhere, who are grateful for a few extra dollars. Cherry Ma, the student, said she had done subtitling for a couple of years.

The pirate manufacturers often pushed for quick results, she said. "When time is tight, you just cover the basics and fill in the gaps," she said, "and if it's full of slang you just have to guess and hope it makes sense. A lot of pirate films have problems like that, because they're done in such a rush."

She often took the work home, receiving about US$12 for a film, though more experienced translators received up to US$30. Films can earn student translators a few dozen to a couple of hundred dollars, depending on the subject matter and on whether they have a script to work from or must work solely from a video copy.

Once the subtitles are complete, the discs are then churned out in the millions in plants hidden in manufacturing cities in southern China, like Dongguan and Shantou. And then a vast web of street hawkers and small shops sells them in virtually every corner of China.

The quality of pirated copies can vary enormously from the shaky, muffled "grab versions" shot with camcorders sneaked into cinemas to crystal clear digital copies made from legitimate DVDs.

Grutka of the Motion Picture Association estimated that last year film piracy in the Asia-Pacific region cost filmmakers US$640 million in sales, with those in China the most frequent violators, accounting for US$168 million. (The International Federation of the Phonographic Industry recently estimated that more than 90 percent of all music CDs sold in China last year were pirated, costing the industry US$530 million in sales.)

Officials for the Guangzhou city and Guangdong province cultural bureaus, which are in charge of preventing piracy, declined to comment on the issue. But in recent years, China has sought to rein in piracy. Shanwei in Guangdong province -- a center of pirate production -- recently was the scene of a ceremonial destruction of 26 million film and music discs. Last year, Chinese authorities say, they seized 14 million pirate VCDs and 6.1 million illegal DVD discs.

But the momentum still seems strongly in favor of China's pirates. Days after the premier of the latest Terminator film in the US, for example, pirate copies were on sale throughout the country.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she