As office equipment goes, few devices have either the romance or the provocativeness of recording machines. Talking to H.R. Haldeman in the Oval Office in 1973, former US president Richard Nixon was recorded by his own machine as saying, "I always wondered about that taping equipment, but I'm damn glad we have it, aren't you?" He didn't remain glad for long. But what if he'd had a digital voice recorder instead of the bulky device bolted to the bottom of his desk? How might history have played out had he been able to scroll through recordings quickly and conveniently, deleting at the press of a button instead of searching through reels of tape archived in the White House basement?

Though his are the most notorious recordings, Nixon wasn't the first US president to bug his own office. In the summer of 1940, Franklin D. Roosevelt invited inventor J. Ripey Kiel to drill holes in his desk through which he could run wires to a microphone hidden in the lamp on top.

Almost every other president since has had a similar set-up that was kept secret from the public and even White House guests. Hoover had one, as did Lyndon Johnson (who recorded over 92,000 hours of tape!) and Dwight Eisenhower. The pen-and-pencil set atop John F. Kennedy's desk also served as the switch to his recording system.

Recording machines have since gone through several incarnations; the dictaphone, the portable tape recorder and the mini cassette recorder, before arriving at the tiny and infinitely more usable devices we have today.

The advantage of today's machines comes as a result of their connectivity to your home computer. Not only can you store your recorded files on your hard-drive or create back-ups on CD, but with voice-recognition software you can automatically convert your dictation or conversations to text.

Although they aren't cheap, these devices aren't much more expensive than portable cassette recorders were when they first came on the market. You can spend from just under US$100 to US$500 or more for a device that -- as a co-worker who recently bought one said -- "it does everything except the cleaning up."

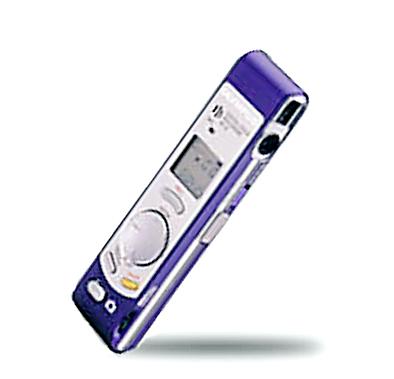

Olympus W-10

US$99.99

This little gadget, about 70g with the batteries in it, can only record for about three hours, which isn't much compared with other models. But, unlike most other models on the market, it can take a snapshot of whoever is speaking, automatically attaching the photo to its corresponding audio file when you download it onto your hard drive. It will take up to 250 photos, although at less than half a megapixel the pictures aren't clear when made bigger than a thumbnail. It allows you to store your recordings in one of two folders which you can then name. Nixon, for example, might have filed his conversations as either "impeachable" or "non-impeachable." You can also move those files between folders and delete single files or whole folders -- a feature "Tricky Dick" would have appreciated.

As with most devices made today, it has voice-activation to allow you to operate it largely hands-off, and can record 45 minutes of sound at 15.5 kHz (a high among models listed here), one hour and seven minutes at a standard-quality 10.3 kHz, or 3 hours of sound that you'll strain to hear for having been recorded at 3.9 kHz. The two AAA batteries that power it can be expected to last about 24 hours before running out when you need the device the most.

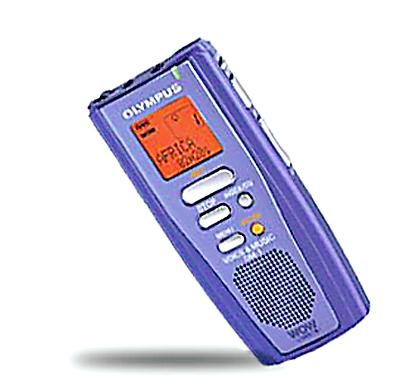

Olympus DM-1

US$250

Although it's more than twice as expensive as the W-10, this Olympus model won't let you take photos. Instead, once your work is over, you can load up to one hour of music in MP3 format onto the device and head out to play. Other than that nifty feature, where the W-10 holds only 3 hours of conversation, the DM-1 can record for up to 22 hours -- something that long-winded LBJ would have fancied. Unfortunately, that's twice as long as its two AAA batteries can be expected to last. Also, where the W-10 can record at three different quality levels, the DM-1 has only two, although it does allow you to store your files in an additional folder.

Another reason the DM-1 costs as much as it does is because it showcases Olympus' new WOW audio technology, which is supposed to produce "rich bass and clear three-dimensional sound with a user-selectable five-setting equalizer." But it produces it through a speaker the size of a postage stamp -- better invest in an upgrade pair of earbuds or headphones.

Mac-heads take note: most of the models available on the market ship with software that is only compatible with PCs. The DM-1 is an exception in that it stores information on SmartMedia cards -- the same cards used in many digital cameras and some cell phones. If you have any other devices that use these cards, you'll certainly want to look for a digital voice recorder that uses the same standard.

Denpa HR-980 & USB-12

US$150 and US$200

Denpa, manufactured both in Taiwan and Korea, is by far the most easily available model in local stores. As such, it's also one of Taiwan's best-selling brands and you're more likely to find a good deal on one than on either of the Olympus models. Bargains aside, it's not the best of the brands available. With both models about the size of a fat pen, the screen on each is too pinched to allow for easy viewing, especially considering it has four folders through which you must navigate your files. The interface isn't as intuitive as with other brands, either.

The main difference between the two is in their recording time. Both models allow you to record at one of three quality levels, but the USB-12 can record for twice as long: 24 hours at an ear-straining low quality compared with 12 hours.

Of course, digital voice recorders aren't for everyone. The only US president since FDR believed to have forgone recording their every conversation was last year's Nobel Peace Prize-winner, Jimmy Carter. His solution? His wife Rosalynn sat by the door in most every Cabinet meeting, pen and paper in hand, taking notes. At least there was no chance of running out of batteries.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she