During a seminar at the Taipei International Book Exhibition earlier this week, local scholars came to the conclusion that Taiwan's literary culture has become marginalized. Instead of looking under their noses and asking any one of the 400 local publishers present why this was happening, they blamed the Chinese movie industry for the lack of interest in, and translations of Taiwanese literature into the English language. According to reports, the global success of Chinese films has meant that international attention has been diverted from things Taiwanese to things Chinese.

Blaming China, however, could be a rather rash move. Of the local publishing houses representing Taiwan at the show -- with the exception of those belonging to the Government Information Office (GIO,

While credit was given to the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation (蔣經國基金會) for being one of the few local groups to publish Taiwanese literature in English, the number of copies sold, however, did raise questions regarding the viability of publishing such works. The example given was that of two recent publications which sold between three and five thousand copies; a number few local publishers seem ready to accept.

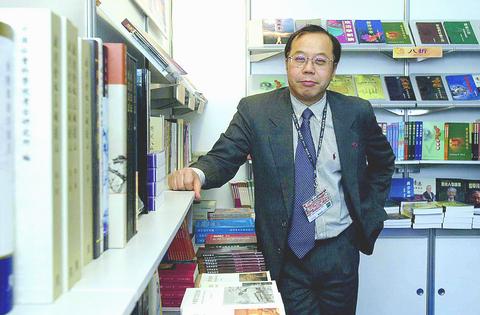

PHOTO: CHIANG YING-YING, TAIPEI TIMES

Finding a niche

Small sales might scare local publishing houses away, but such sales are not only the norm, but have become the backbone of Hong Kong's Chinese University Press. As it is one of the few publishing houses to print academic and general tomes as well as journals focusing solely on Greater China, if you've ever been a student of East Asian studies you will have read -- albeit not out of your own choosing -- one or more of the press's publications.

Founded in 1977 as the publishing house of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, the company has been at the forefront of the publication and translation of academic texts dealing with all things relevant to Greater China and the study thereof for a quarter of a century.

PHOTO: SEAN CHAO, TAIPEI TIMES

As the press now publishes more than 40 titles per year and carries a back-list of upwards of 800 titles, financial loss is an aspect of publishing books relating to Sinology that you simply have to grin and bear, according to Steven Luk (

"Not all, but many of the academic books we publish are published at a loss. After all, interest in a specific geographical or historical aspect of Fujian Province is pretty minimal," Luk said. "Publishing house profits come from reprints, which in our case are, for the most part, our textbooks.

With the exception of a weighty tome dealing with Hong Kong's tricky tax laws, very few, if any, of the company's publications exceed sales of five-and-a-half thousand copies per year, with sales of between three and five thousand considered "good."

The company's publications might not be heading for the bestseller lists, but this hasn't stopped several of its titles from becoming the bibles of Sinology, regardless of the small numbers published and sold. Published in 1993, A History of Chinese Calligraphy by celebrated Chinese artist and calligrapher Tseng Yuho (

Press freedom

The return of Hong Kong to Chinese rule in 1997 and its subsequent desultory affect on freedom of speech has not, according to Luk, affected the university press.

"Much of the trouble that has arisen has involved the media. Publishers have been left alone," Luk said. "And of course, publishing books in English and other non-Chinese languages means that officials are less likely to see them, let alone bother to read them."

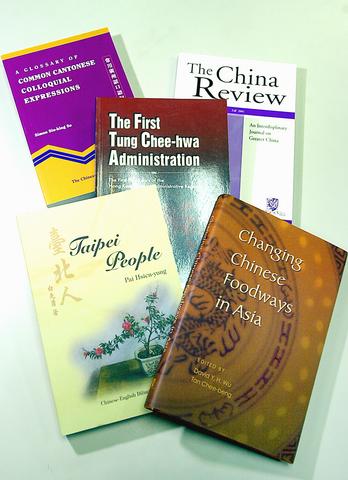

A case in point is an English-language book published by the university press about the first five-year term of Hong Kong's Chief Executive Tung Chee-hwa (

"Our agents in China have had no qualms with selling the English-language book about Tung Chee-hwa on the grounds that no one reads it,'" Luk explained. "It's a different story with books in Chinese that touch on such topics, however. Our agents in China won't touch them."

Broadening its scope in recent years, the publishing house now produces titles on business management, education, social and natural sciences, and national healthcare systems. But its most lucrative publications in recent years have been textbooks.

"We've had a lot of luck with our textbooks both at home and abroad. Colleges and universities in the US now use them as part of their Chinese-language curriculums," Luk said. "And of course there's the local market, with more and more foreigners taking the time to learn Chinese, be it Mandarin or Cantonese."

Colorful language

Making textbooks might be cost effective, but it still isn't a risk-free venture. According to Luk, the company's most recent phrasebook dealing with informal aspects of the Cantonese dialect needed a complete overhaul after publishers realized some of the colloquialisms were too colorful. "The Cantonese have a passion for using what in English would be considered four-letter words in everyday speech," Luk explained with a smirk. "Because of this, a few rather rude phrases managed to make their way into the first edition. Needless to say, we had to remove them before the book was reprinted."

Although many of the books published by the Chinese University Press deal with Hong Kong or China, Luk is well aware of the void in the Taiwan-related market. This is one of the

reasons the company recently opted to re-publish Pai Hsien-yung's (白先勇) 1983 collection of short stories, Taipei Voices, in bilingual format.

"We have always had a good relationship with Taiwan's academics and often call on them to act as referees and consult them before we publish certain works. But we only recently set out to publish works such Taipei Voices in English," Luk said. "And with the ever-growing number of foreigners living in Taiwan, I'm pretty hopeful that these books will find an audience."

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any

You can tell a lot about a generation from the contents of their cool box: nowadays the barbecue ice bucket is likely to be filled with hard seltzers, non-alcoholic beers and fluorescent BuzzBallz — a particular favorite among Gen Z. Two decades ago, it was WKD, Bacardi Breezers and the odd Smirnoff Ice bobbing in a puddle of melted ice. And while nostalgia may have brought back some alcopops, the new wave of ready-to-drink (RTD) options look and taste noticeably different. It is not just the drinks that have changed, but drinking habits too, driven in part by more health-conscious consumers and