It is interesting that Myxomycity, an exhibition by contemporary Taiwanese architects at Taipei's Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), takes its name from a special class of organism known as slime molds.

Myxomycetes, roughly pronounced "mix-o-my-keets", designate a curious biological group in an indefinite territory between fungi and simple animals. It grows on damp logs and amid forest detritus in Taiwan and many other parts of the world, beginning life as a single-celled amoebae, which instead of splitting into two new organisms, grows into a multi-nuclear plasmodial slime. This slime has the limited ability to ooze from place to place, leaving behind it a kind of shimmering snail-trail of waste. When it finds a good spot, it can produce 1mm or 2mm-tall mushrooms or other fungal forms, which release spores that eventually produce new amoeba to complete the reproductive cycle.

What myxomycetes have to do with Taiwanese architecture, however, is not entirely made clear, especially in this exhibition. Exhibition materials try to explain the link with a few vague or trendy concepts like resistance to evolution, globalization, and redefining identity. But in the end, Myxomycity comes off as a clever pun rather than a well-carried-out metaphor. It's a pity, because the metaphor had potential.

COURTESY OF MOCA

Like the title, the exhibition's success is willy-nilly. But what is valuable about the show and what makes it worth seeing is the ideas put forward, though not always clearly, by the three architects in the show, Cheng Shao Cheng Tao (程紹正韜), Liao Wei-li (廖偉立) and Hsieh Ying-chun (謝英俊) and the curator who grouped them, Roan Ching-yueh (阮慶岳). The four advance ideas for local architecture -- including the aesthetic possibilities of cheap materials, the relationship of architecture to nature and traditional styles, and how to break away from the reinforced concrete box -- that represent important, new ways of thinking about building and buildings, both locally and globally.

Due to good foresight by MOCA, a world/historical context for work of these Taiwan architects is just upstairs in a very good and concurrently running show, Architecture for the New Millennium. It highlights the work of one of the greatest contemporary architects, Frank Gehry, and four other highly influential Southern California architects and firms. By cross-referencing the two shows, you can get an idea of the lineage of certain ideas in contemporary architecture and how local architects have appropriated, translated, and in some cases rejected them.

Koning Eizenburg, for example, is a Southern California firm that has faced entire, large buildings in corrugated aluminum and that once designed a complete house out of plywood. They've very successfully propagated a kind of Ikea architecture, or an architecture that lends beauty to standardized, mass produced materials and knows how to fit in to what's usually already a synthetic environment. So their designs are attractive, but never at the expense of a project's social identity. In other words, their schools always look like schools, their apartments like apartments, and their houses like homes.

COURTESY OF MOCA

Hsieh Ying-chun, in what is easily the best portion of Myxomycity, has applied similar prefab and DIY ideas -- as well as a very community-oriented conscience -- to a housing reconstruction project now underway for victims of Taiwan's September 2000 earthquake. Following the disaster, he won a competition for the rebuilding of an entire village with a plan that was so low budget it generated controversy among contractors and other interested bidders. The plan called for houses to be made of little more than steel frames, plywood and bamboo. In its implementation, the structures have been so easy to make that construction has generally taken one week or less, and labor has been supplied by the affected community, which was largely unemployed following the quake.

To represent this ongoing slice of reality at the museum, Hsieh enlisted volunteers to build one of his NT$500,000 or less houses in MOCA's front courtyard. The project was completed in two weeks during July, but will only be opened to the public this weekend after finally receiving a building permit from Taipei City Government. After the structure is dismantled on Sept. 22 at the exhibition's close, its materials will be transported to Nantou where it will be reassembled as part of the earthquake reconstruction project.

Inside MOCA, a small gallery devoted to Hsieh's rebuilding scheme has its walls covered with gems of byproduct documentation describing everything from preliminary assessments to continuing work. If you can read Chinese, the collection is full of wonderful asides, including everything from Hsieh's resume to the story of a man who, after his newly reconstructed three-story house saw its ground floor become a basement in last year's landslides, placed the main door on the third floor in anticipation of further submersion.

Due coverage is also given to the situation of the Thao (

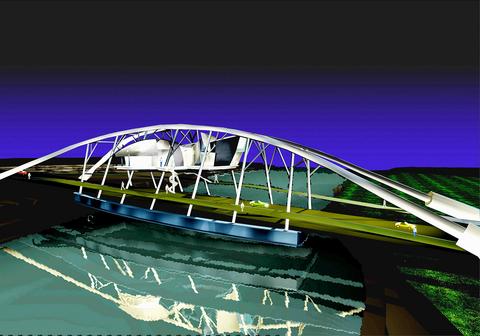

Besides Hsieh's contribution to Myxomycity, a room packed with architectural models and sketches by Liao Wei-li is really the only other part of the show worth seeing. It displays an interesting body of work -- most projects are not yet built -- that range from a radio broadcast tower whose structure was derived from a bamboo leaf to a Gehry-inspired and exfoliating coffee shop that is to be suspended amid the supports of a bridge near Hsinchu's Chiao Tung University.

The gallery occupied by Cheng Shao Cheng Tao is unfortunately an incompletely conceived attempt at installation art rather than an introduction to some interesting ideas on architecture. Cheng's buildings, like an award-winning design for a Toyota's Taichung headquarters that was recently built, incorporate heavy landscaping and often roofs of grass or other vegetation. Like the designers of US headquarters for companies like Microsoft and AT&T, he has come to the conclusion that corporate power should humanly and inconspicuously sprawl across the landscape rather than projecting vertically in columns of egotism. But his back to nature philosophy seems merely naive in a sub par installation, rather than carrying force as it does in his buildings.

So while many of the ideas driving Myxomycity are sound, their transmission to the show's viewers is often unaccomplished. In this way, Myxomycity comes off as an unfortunately mixed bag.

What:Myxomycity

Where:Taipei's Museum of Contemporary Art

When:Through Sept. 22

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

It was on his honeymoon in Kuala Lumpur, looking out of his hotel window at the silvery points of the world’s tallest twin skyscrapers, that Frank decided it was time to become taller. He had recently confessed to his new wife how much his height had bothered him since he was a teenager. As a man dedicated to self-improvement, Frank wanted to take action. He picked up the phone, called a clinic in Turkey that specializes in leg lengthening surgery — and made a booking. “I had a lot of second thoughts — at the end of the day, someone’s going

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Standing on top of a small mountain, Kim Seung-ho gazes out over an expanse of paddy fields glowing in their autumn gold, the ripening grains swaying gently in the wind. In the distance, North Korea stretches beyond the horizon. “It’s so peaceful,” says the director of the DMZ Ecology Research Institute. “Over there, it used to be an artillery range, but since they stopped firing, the nature has become so beautiful.” The land before him is the demilitarized zone, or DMZ, a strip of land that runs across the Korean peninsula, dividing North and South Korea roughly along the 38th parallel north. This