Le Corbusier may be one of the 20th century's greatest architects, but few know that he spent the first 33 years of his life as a painter, interior designer and factory manager. A new exhibition at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM), Le Corbusier: Morceaux Choisis, 1912-1965, takes this lesser known, non-architectural side of the architect and confronts it with scores of elevations, plans, sketches and models of his famous "white houses," the church at Ronchamps and other contributions to the architecture textbooks. Thus the opus of the revered master, which is already so well known, is endowed with the context of the ideas underlying it, architectural and otherwise. It is unlikely that such a provoking, in-depth look at this modernist visionary will ever come through Taiwan again.

Even more special, the show was exclusively created for TFAM. Unlike travelling exhibitions that local museums usually have to purchase, Morceaux Choisis(which roughly translates as "Selected Fragments") was uniquely conceived for display in Taipei by curator Jacques Sbriglio, who drew every document, model and canvas -- several 80-years-old or more -- from the archives of the Fondation Le Corbusier in Paris. Once the exhibition is over, the works will return to hibernation in France.

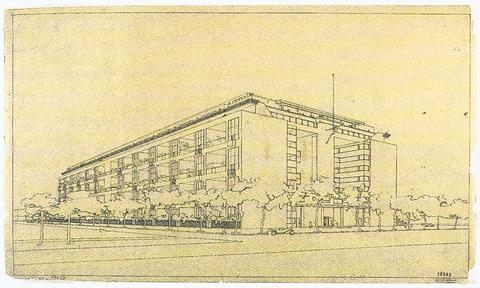

Le Corbusier will forever be known as the inventor of an architecture for the industrial age. He believed in pure geometrical forms and designed cheap, modular structures of ferroconcrete that could be mass produced. He designed buildings with internal supports that freed the walls from having to hold up the roof, so for the first time, exteriors were striped with bands of horizontal windows. These are the tools he used to form his rigidly conceived, white boxes.

Not just an architect, Le Corbusier was also a socialist and a utopian, and his maxim went: "the house is a machine for living in." And like all of the modern uptopians, his belief in unlimited social progress through technology was to prove wrong. At one point he suggested a plan to raze part of Paris, replacing it with 18 mega-skyscrapers, each surrounded by a huge, hygenic buffer of parks and gardens. Such ideas eventually came to fruition in the hands of others through structures like the public housing projects of the US and the workers' dormitories of the Eastern Block ? depressing monuments to conformist living. But if Le Corbusier's vision of life in the modern age was cold and authoritarian, he still introduced ideas on how to accommodate mass-produced living that others were later able to adapt and make more human.

Born Charles-Edouard Jeanneret in Switzerland in 1887, it wasn't until the age of 33 that he adopted his maternal grandfather's name, Le Corbusier, to distinguish his architectural work from his painting. By then he had already been in Paris for four years, where art was already in the process of dissecting both the real and visual worlds. The Fauves had already made painting unnatural, the Cubists were breaking forms, and the Dada movement was both embracing machine age aesthetics and introducing a psychological perspective that would give way to the violent emotions of the Expressionists and the dream fascination of the Surrealists.

Morceaux Choisis begins with Le Corbusier's two dimensional works of this period. Watercolors and paintings of the early 1910s are those of a young artist, eclectic and searching through the various styles of his time. Towards the end of the 1910s he starts to find himself in a more determined brand of Cubism, in which he simplifies natural objects, mostly still lifes, into a purified geometry of regular shapes, angles and curves. It is quite different from the shattered fragments found in the analytic cubism of his contemporaries Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso.

Fondation Le Corbusier director Evelyn Trehin cites Le Corbusier's closest painting influence as Fernand Leger, whom Le Corbusier met in 1920. Both moved out of Cubism looking for a more pure geometry, one that Le Corbusier found everywhere from the Parthenon in Athens, with its round columns, rectangular plan and triangular pediments to the new clear-cut geometry of the automobile.

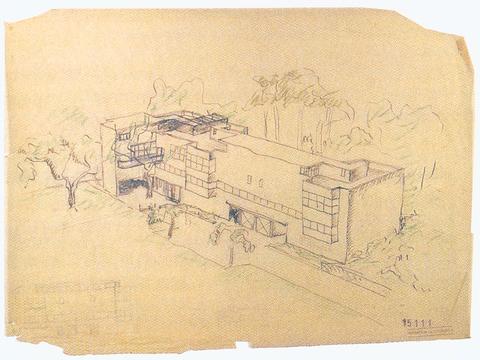

In 1922, Le Corbusier built his first white box, the Maisons Citrohan. In that and other designs -- the Villa Savoy (1928) and the more massive and severe Unite d'Habitation (1945) -- the principles applied are reflected in his paintings. Natural forms are simplified and compartmentalized into a purist's geometry; only the most basic forms are used.

But over a lifetime, Le Corbusier's ideas softened. Later paintings, which date as late as 1956 in the exhibition, show more irregular shapes, broken lines and a new vocabulary of curves. Likewise, his Notre Dame du Haut at Ronchamps (1951), which is perhaps his masterpiece, is a structure consisting predominantly of warped forms and irregular geometry.

In viewing Morceaux Choisis, it is hard not to see these similarities and make these kinds of comparisons. Yet to the curator's credit, he has not imposed his own decisions on how exactly these marvelous and seldom seen fragments of Le Corbusier's past are to form a congruous whole. In the exhibition space, architecture forms one cycle, and painting another. Connections may be drawn, or not.

Le Corbusier: Morceaux Choisis, 1912-1965 opened yesterday and is on display through Oct. 27.

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Jan. 12 to Jan. 18 At the start of an Indigenous heritage tour of Beitou District (北投) in Taipei, I was handed a sheet of paper titled Ritual Song for the Various Peoples of Tamsui (淡水各社祭祀歌). The lyrics were in Chinese with no literal meaning, accompanied by romanized pronunciation that sounded closer to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) than any Indigenous language. The translation explained that the song offered food and drink to one’s ancestors and wished for a bountiful harvest and deer hunting season. The program moved through sites related to the Ketagalan, a collective term for the

As devices from toys to cars get smarter, gadget makers are grappling with a shortage of memory needed for them to work. Dwindling supplies and soaring costs of Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) that provides space for computers, smartphones and game consoles to run applications or multitask was a hot topic behind the scenes at the annual gadget extravaganza in Las Vegas. Once cheap and plentiful, DRAM — along with memory chips to simply store data — are in short supply because of the demand spikes from AI in everything from data centers to wearable devices. Samsung Electronics last week put out word