The master and his student sat privately in the master's study. The master spoke, saying, "my student, you must flee to the outlying island. The new regime is certain of victory and with their victory will come a time where our religion and our martial art will be suppressed. To ensure the survival of the martial arts I have passed on to you, I want you to leave this land and journey to the island. There, hopefully, the art I have transmitted to you will be preserved from the coming darkness."

Sounds like a kung fu novel or maybe a plot to a Star Wars movie? It was an actual event. The martial arts master was Zhang Zhao-dong (

At the end of the Chinese Civil War, Taiwan became an important repository and conservatory of many aspects of Chinese culture such as painting, calligraphy, opera and traditional martial arts. In particular, Taiwan provided a refuge for practitioners of the three internal martial arts of tai chi chuan (太極拳), hsing yi chuan (形意拳) and pa kua chang (八卦掌).

Wang Shu-chin (1905-1981) was one of many martial arts masters who sought refuge in Taiwan following the Chinese Civil War. Over the years, the three internal martial arts that he brought with him have taken firm root in Taiwan and even expanded further to the US, Australia and beyond.

The internal martial arts that Wang Shu-chin practiced, tai chi, hsing yi and pa kua have a number of characteristics that link them together. They are each based in Taoist philosophy and emphasize the development and use of chi (氣), which is the term used in traditional Chinese medicine for the life force. The three internal martial arts seek to enhance the practitioner's overall mental, physical and spiritual state. These three martial arts can perhaps best be described as forms of moving meditation that, by their practice, give rise to martial ability.

Chi is central to the internal martial arts. It has been defined many ways and is an important part of many traditional Chinese arts. It is also an intrinsic part of traditional Chinese medicine. Scholars generally define it as the force or energy that animates all living things -- a kind of "elan vital." Chi has been likened to a flow of fluid or of electricity through the practitioner's body. Control and use of this energy is the goal of each of the three arts Wang brought to Taiwan.

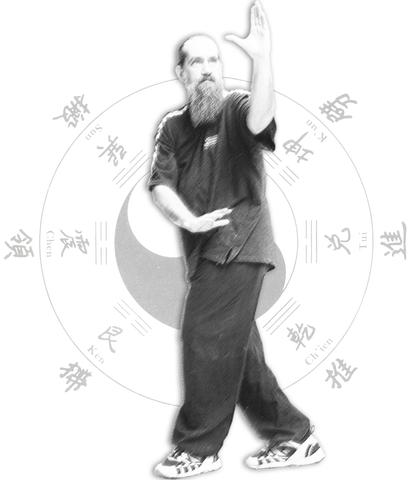

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS LIBRARY

These arts are referred to as "internal" because their training methods place an emphasis on the practitioner "looking inside" themselves and studying how their mind interacts with physical movements through breath and chi. Along with this is an emphasis on how their mind, breath and chi work together to create a very healthy, integrated individual.

But the arts are also extremely effective in combat, as revealed in many stories involving Wang Shu-chin. The source for most of the historical information about Wang is his student, Wang Fu-lai (

According to him, Wang Shu-chin was born in 1904 as the sixth son in a family of farmers living in a village about 32km from Tianjin City in northern China. His older brothers were content to farm, but Wang wanted to be part of a bigger world. So, with his parent's permission, he left home when he was 14 years old and traveled to Tianjin seeking fame and fortune. There he found work as an apprentice in an international trading company.

By the time of his arrival in Tianjin, Wang was already, as his student Wang Fu-lai puts it, "a man of impressive size and unusual physical strength." He was also very interested in martial arts and religion and began to search for martial arts instruction. By chance one day, a senior student of the famous martial arts master Zhang Zhao-dong came to the business where Wang worked. This chance meeting led to the then 18-year-old Wang studying under Zhang.

Under Zhang's instruction, Wang learned the two arts for which he would later become famous; pa kua chang and hsing yi chuan. Pa kua chang means "eight diagram palms" and refers to the eight core diagrams which make up the I-Ching (

The practice of pa kua chang consists of moving around in a circle while performing eight different martial arts techniques which use the palms to strike an opponent. Each of these eight techniques corresponds to one of the eight fundamental diagrams in the I-Ching. Maneuvering around to the side or back of the opponent, a practitioner strikes using one of the eight techniques. The art also emphasizes throwing the opponent -- much like in judo -- as well as various arm locks.

Wang could perform pa kua chang with dizzying speed, rapidly turning back and forth around the circle. Despite his size, he was able to move with incredible speed and agility, which he attributed to his study of the art form.

While pa kua focuses on circles, its sister art, hsing yi focuses on lines and linear attacks. Hsing yi consists of a set of five forms performed up and down along a straight line. These five forms correspond with the five elements in traditional Chinese philosophy: earth, water, fire, wood and metal. A hsing yi practitioner meets their opponent's attack on an oblique angle then overwhelms them with a series of rapid punches. The art, like pa kua, puts an emphasis on the use of chi and the integration of the whole body into a coordinated unit.

Hsing yi also trains its practitioners to be able to withstand the force of an opponent's blow. Wang was famous for his ability to withstand blows to any part of his body, excluding his head and groin. His "iron body" drew considerable interest from practitioners both in Taiwan and abroad.

In 1949, Wang's teachers sent him to Taiwan. They surmised -- correctly, history would prove -- that the change in China's government would likely lead to a suppression of martial arts. In order to ensure the survival of pa kua chang and hsing yi, Wang took them for safekeeping to Taiwan. He arrived in a fishing village in northern Taiwan in late 1949 and started his own rice business.

He also began to teach his martial arts and quickly gathered around him a number of dedicated students. Several years later he moved south to Taipei to open a rice shop. There Wang's businesses thrived and he became a fairly wealthy man.

He was also a man in demand. Word of his skill in martial arts spread and many wealthy people and politicians sought out Wang's instruction. While he considered his prominence flattering, given the political intrigues of the time, it was also dangerous. Distancing himself from this, Wang moved south to Taichung in 1952.

He continued to teach martial arts in Taichung where his reputation as a skilled hsing yi and pa kua practitioner preceded him. As number of established martial artists in the south of Taiwan sought to "test" Wang's abilities. Challenge matches in those days could be very rough affairs where the result was sometimes death. Wang successfully met all challengers and so cemented his reputation as Taiwan's most skilled hsing yi and pa kua fighter. Wang became known within Taiwanese martial arts circles as "the unvanquished."

His teaching too remains unvanquished. The martial arts association he formed in Taichung still teaches Wang's martial arts as he had. The association is now headed by Wang Fu-lai, who began studying under Wang at the age of 15.

After several years, Wang Fu-lai became the elder Wang's only personal student, meaning that he was permitted to live in Wang's house and be by Wang's side at all times. Today, the Cheng Ming Martial Arts Association is active not only in Taiwan, but in Argentina, Israel, the US, Japan and Australia.

This worldwide spread of the arts is evidence that Wang Shu-chin fulfilled his mission of preserving and spreading the martial arts that he had been entrusted with by his masters.

Under pressure, President William Lai (賴清德) has enacted his first cabinet reshuffle. Whether it will be enough to staunch the bleeding remains to be seen. Cabinet members in the Executive Yuan almost always end up as sacrificial lambs, especially those appointed early in a president’s term. When presidents are under pressure, the cabinet is reshuffled. This is not unique to any party or president; this is the custom. This is the case in many democracies, especially parliamentary ones. In Taiwan, constitutionally the president presides over the heads of the five branches of government, each of which is confusingly translated as “president”

Sept. 1 to Sept. 7 In 1899, Kozaburo Hirai became the first documented Japanese to wed a Taiwanese under colonial rule. The soldier was partly motivated by the government’s policy of assimilating the Taiwanese population through intermarriage. While his friends and family disapproved and even mocked him, the marriage endured. By 1930, when his story appeared in Tales of Virtuous Deeds in Taiwan, Hirai had settled in his wife’s rural Changhua hometown, farming the land and integrating into local society. Similarly, Aiko Fujii, who married into the prominent Wufeng Lin Family (霧峰林家) in 1927, quickly learned Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) and

The Venice Film Festival kicked off with the world premiere of Paolo Sorrentino’s La Grazia Wednesday night on the Lido. The opening ceremony of the festival also saw Francis Ford Coppola presenting filmmaker Werner Herzog with a lifetime achievement prize. The 82nd edition of the glamorous international film festival is playing host to many Hollywood stars, including George Clooney, Julia Roberts and Dwayne Johnson, and famed auteurs, from Guillermo del Toro to Kathryn Bigelow, who all have films debuting over the next 10 days. The conflict in Gaza has also already been an everpresent topic both outside the festival’s walls, where

The low voter turnout for the referendum on Aug. 23 shows that many Taiwanese are apathetic about nuclear energy, but there are long-term energy stakes involved that the public needs to grasp Taiwan faces an energy trilemma: soaring AI-driven demand, pressure to cut carbon and reliance on fragile fuel imports. But the nuclear referendum on Aug. 23 showed how little this registered with voters, many of whom neither see the long game nor grasp the stakes. Volunteer referendum worker Vivian Chen (陳薇安) put it bluntly: “I’ve seen many people asking what they’re voting for when they arrive to vote. They cast their vote without even doing any research.” Imagine Taiwanese voters invited to a poker table. The bet looked simple — yes or no — yet most never showed. More than two-thirds of those