At 4pm Chang Chen-yue (

Does A-yue have attention deficit disorder, or is he just a really energetic young man in the process of waking up? Before too long, he answers the question himself by creasing his brow and getting cerebral, as he reflects on Who Stole My Cheese, by Spencer Johnson, the book he read most recently.

"It's a great story of these kids and these mice who go around this maze looking for cheese. The mice are constantly looking because they're stupid, right? But the kids are smarter and have these methods for finding cheese faster, but they're lazy. Anyway, the point of the whole story is that there's never a moment's rest. You've gotta keep moving on, doing new things. And that's how I see life." A-yue seems to have found a parable to sum up his life.

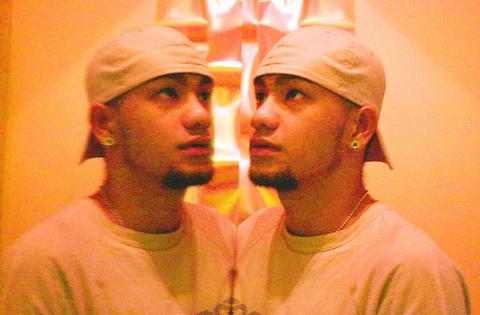

PHOTO: CHIANG YING-YING, TAIPEI TIMES

A tireless, million album-selling musician, he's also a stand-in psychologist for his friends and a businessman with a strong pragmatic streak. On top of that, he's a genuinely nice guy, soft-spoken and with a gentle temperament. He's anything but the angry, in-your-face rocker one may expect from a man whose anthems include lyrics like "you've got a fuckin' trouble" and who says he "grew up" at Spin, Taipei's notoriously dingy rock night club.

In reality, A-yue, who's now 27, grew up in Ilan, where he spent a leisurely 17 years before moving permanently to Taipei. Reflecting on his days in Ilan, his voice is tinged with nostalgia. "The air's really nice there. There's no pollution and there are these great empty beaches that no one knows about." Joking at himself slightly, he concedes it's the usual pitch from Ilan natives.

By junior high school, A-yue began to realize that he was a bit unlike others his age. "All the others in school were busy chasing girls and getting into fights. But I was kind of dopey and didn't get into all that. It's not that I was a loner, or didn't have any friends, I just felt there was a distance between me and them." Maybe it was because of his Amei background, he says. "I grew up around Chinese people in Ilan, so I'm used to them. But there were times I felt I just couldn't share my feelings with others. Maybe it's a different heart."

His biggest revelation musically was when he first heard Guns n' Roses and said to himself "Now that's rock!" But popular music at the time consisted almost exclusively of heavily produced love songs by packaged singer/songwriters. A-yue's friends hated Guns n' Roses and he found his eclectic musical tastes becoming another divide between himself and his peers.

A-yue got into the music business almost accidentally, when, at 17, he entered a singing competition at the suggestion of a friend and against all expectations won first place. Immediately afterward, Polichiayin Records (

A-yue is frank about his early work. "There are a lot of cheesy love songs on my first albums. But I don't care. I did them honestly because I like the songs, too. My friends sometimes point at the stuff I did before and laugh. I don't care. Let them laugh.

"When I was 18 and putting out my first records, I didn't know very much about music and would pretty much just listen to what others said I should be doing. But after I finished military service, I really made a point of trying to develop my own style, find my own way of creating music. I'm not saying that what I did before military service wasn't good. It was just part of the process."

In the five years since leaving the army, A-yue has become a reluctant spokesman for a new generation of Taiwanese youth, whose lives of relative material comfort and abundant information have brought new forms of urban ennui. One of his most popular songs, called Dad, I want your money, is a blunt celebration of slacker ethics, while other songs are explosive rock numbers with expletive-filled lyrics.

Now he's working on a new album due out in December, which keeps him up until dawn at a Yangmingshan studio. He describes the album as a "back-to-basics" re-gathering of the creative spirit that welled up after he finished military service in 1996.

"The music I've made over the years has gotten progressively more complex and technical. This time, I want to try something else. I want it to be simpler, pure rock. I'm thrashing out these songs and they're really bare with riffing power chords and great melodies.

"Lots of the chords I come up with don't actually exist. Our guitarist sees them and is like `that's not a chord.' I think it's better that way. I don't want to draw limits around the music by making it overly technical. The emphasis is on the sound, that's all." He says the album will be more like What a boring afternoon (1997,

"That's still my favorite album of mine. Sometimes I think when I was making Secret Base (1998,

But, he confesses that his lyrics are not accounts of his own angst and are instead often inspired by the problems encountered by his friends. "I live pretty well and feel pretty good about what I've done in my life, so I don't have much reason to complain or be bitter. But friends just tend to come to me to talk about their problems and I use their stories as inspiration to write my songs."

He tells of a song he's writing about a friend who fell in love with a "real pig head of a man." Now the woman is pregnant and her friends all shun her for being with the reviled man.

"Her friends aren't talking to her anymore, but she's sticking through it for her kid and because she's in love. I found that kind of dedication really touching, really great."

Given his long history in rock and ballads, Orange is clearly a major departure into new territory.

"Orange is an entirely different project, not an evolution of my tastes, that's why I don't put my name on the albums. Maybe if I did, they'd sell a bit better.

But actually it's just an outlet for this music I've got going through my head." The two Orange records are a bit of a hodge-podge of the electronica genre and are, in A-yue's own words, "not that great."

He's maybe being overly humble, though, since his appearance in mid-October as guest DJ at Room 18 raised more than a few eyebrows, and not just because it was that kid who sang "Free night, I wanna get high" behind the turntables.

Some of the tracks are jazzy, with heavy, funky basslines and some credible back-up diva singing. These have the most potential mass appeal, but A-yue, who has made his own calculations of the market in Taiwan, is not betting his future on Orange. "Electronica doesn't have much of a market in Taiwan. That's just the way it is." He's even taken into consideration how his fans would perceive his jump to electronica, with its connections to rave culture and drugs.

"I did think about how my fans would see it. I first got into electronica before ecstasy got so big, back when it was more about a new kind of music. The ecstasy thing has gotten totally out of control since then. I'm not going to say that that's good or bad, but it's not what I'm into."

At this point, he cracks a wry smile, "For me, it's about a natural high."

"Most importantly, I thought about not doing Orange and it just seemed like a pity. You can't confine yourself to one thing or one style. You have to try new things."

As he talks -- and he talks without prompting -- he completely ignores the food and drink before him as he smokes 555 after 555. The conversation repeatedly moves toward the business aspect of his life -- the market for electronic music, his work importing Freshjive clothes, his desire to go into import/export after he tires of music.

He shrugs when he says he's sold a million records. "Just a million." He's not being pompous, he obviously envisions big things, and for that he looks to China.

"That's where the big market is. There's 20 million people in Shanghai alone! ... We should just unify right away. All these Chinese going at each other, with people saying `Ah, we should kick you mainlanders out.' Well, what about us Aborigines? We were here first. We should send your asses packing!"

Then, A-yue catches himself on the verge of a tirade and starts to laugh. "I hate politics." He eases back into his chair and rubs his brow where he has a 5cm scar from where he fell down the stairs as a kid playing Superman. "To be honest, I probably think more about the market than Magic Stone does. It's not a huge concern, but I definitely try to make things that people will like. I set my own sights."

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a