This large-scale retrospective exhibition, focusing on the culture of one ethnic Chinese region, features 400 artifacts on loan from almost 30 museums in northern China.

The works span from the Neolithic Period to the Ching dynasty and represent a number of ethnic subgroups in northern China, in areas located mostly in current-day Inner Mongolia. Cultural relics from the region include ornaments in gold, silver, bronze and jade; costumes; stoneware; sculpture; and daily utensils made from bronze, porcelain, pottery and copper.

The nomadic cultures of the steppe region that survived for thousands of years are distinct from the agricultural interior of China, south of the Great Wall.

PHOTO COURTESY: NATIONAL PALACE MUSEUM

"For people with a romantic disposition, the ever-stretching steppe is just like the vast expanse of the ocean, full of imaginative allure," says Tu Cheng-sheng (杜正勝), director of the National Palace Museum, where the show is taking place. Tu adds that Inner Mongolia is significant as a good example of an ethnic melting pot and the artifacts on view are solid testimony to this point.

The civilizations of each ethnic subgroup in northern China are showcased in the various sections of the exhibition. The general term of Chinese is said to consist of seven ethnic groups: Han, the majority, and the minority groups of Man, Mongolians, Hui, Tibetans, Miao and Yao. However, more sub-ethnic groups emerged over history, eventually making up the huge population of the ethnic group known as Chinese. Inner Mongolia, for example, has been inhabited by seven ethnic subgroups: Tunghu (東胡), Hsiungnu (匈奴), Wuhuan (烏桓), Hsien-pei (鮮卑), Tu-chuen (突厥), Khitan (契丹), and Mongols (蒙古).

Upon entering the exhibition, there are four sections to the right and left. In the first section on the right are artifacts from the earliest period, dubbed the Pre-Nomadic Period (80th to 16th century BC).

PHOTO COURTESY: NATIONAL PALACE MUSEUM

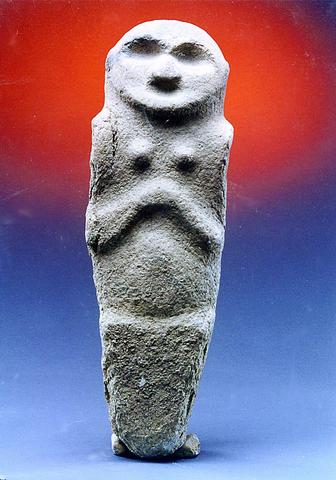

Artifacts from this period include jade pieces and sculptures of humans and folk gods. The jade wares originate from the so-called Red Mountain Civilization (紅山文化) of about 5000 to 6000 years ago and reveal sophisticated designs and workmanship. Among the favorites is the pig-dragon jade piece (玉豬龍). A red clay sculpture of a female deity from this period on display is distinctive for its obscured facial and body features -- a departure from sculpture in earlier periods that emphasized female breasts and buttocks.

The subsequent period marked the beginning of the nomadic lifestyle by the Tunghu people. The artifacts from this period are dubbed "animal style," as animal themes dominated this group's cultural and artistic creations. Bronze swords or daggers inscribed with simple, classic and elegant animal totems are the featured relics from this period, particularly from the excavation sites dubbed "Upper-Hsia-chia Civilization" (夏家店上層文化).

The exhibitions to the left of the entrance, marked by a blue banner, are relics from the Hsiungnu tribe, a civilization formed in 206 BC. The Hsiungnu are known as a horse-riding, animal-hunting people with a fierce fighting spirit. They created a unique nomadic culture with the Tunghu people which had a major impact on horse-riding tribes.

PHOTO COURTESY: NATIONAL PALACE MUSEUM

The central artifact in this exhibit is a hawk-shaped gold hat ornament supposedly worn by the Hsiungnu king. Animal symbols, each topped by a colored hawk, emphasize the power and vigor of the king.

The Hsien-pei and Tu-chueh tribes occupied the vast land of the northern steppe from the 4th to the 10th centuries. Hsien-pei people built the empire of Northern Wei and their cultural relics have a strong animal-theme. Different from the preceding Hsiungnu artifacts are the gold ornaments of horse heads with deer antlers. The Tu-chueh people's domain was bordered by the powerful Tang empire to the south, bringing influences from far away places in neighboring China. Some of the examples in the show include a gold and silver plate with an exotic fish pattern that is said to be of Indian mythological animals and a silver pot capped with the figure of a human head, suggesting a Persian influence.

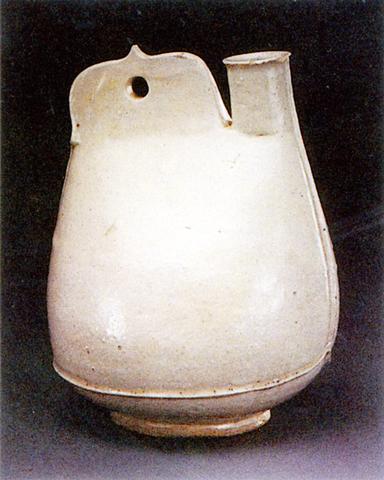

The Khitan people established the Liao Empire in 907 AD, which lasted until the early 13th century. They left behind a rich heritage as witnessed in the saddlery, gold and silver vessels and porcelain wares on view at the exhibition. The most representative items from this period are the cockscomb flasks and liquid containers that functioned as canteens for the nomads.

PHOTO COURTESY: NATIONAL PALACE MUSEUM

The show also features a large section on Mongolian culture. The Mongolian emperor Genghis Khan (1162-1227) conquered the region in the early 13th century, establishing a base from which he created a vast empire spanning Europe and Asia. His reign left behind spectacular multi-cultural relics, some of which are on exhibit. Featured in this section are Buddhist sculptures, gold items, musical instruments, and porcelain pieces tinged heavily with Tibetan and Islamic elements. Chinese porcelain ware from inland China that turned up in Inner Mongolia, a sign of flourishing trade at the time, are also on exhibit. Also not to be missed in this section are the pottery figurines and saddlery.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a