US President Donald Trump’s relentless attacks on US Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, together with his destabilizing foreign policy — notably the seizure of then-Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro, and subsequent threats to bomb Iran and invade Greenland — have called into question the entire post-World War II international order, including the dominance of the US dollar. There has never been a more appropriate moment to reflect on the dynamics that have kept the international monetary system relatively stable over the past half-century.

Stability has persisted despite a fundamental asymmetry inherent in the US dollar’s role as a global reserve currency: to supply the world with US dollar liquidity, the US must run a current-account deficit, buying more from abroad than it sells. At the same time, it issues debt that foreign governments and investors are willing to use as a reserve asset.

As a result, US borrowing costs have remained consistently low, enabling the federal government to expand its fiscal space on the back of foreign savings. This is what then-French minister of finance Valery Giscard d’Estaing had in mind when he famously complained in the 1960s about the US dollar’s “exorbitant privilege.”

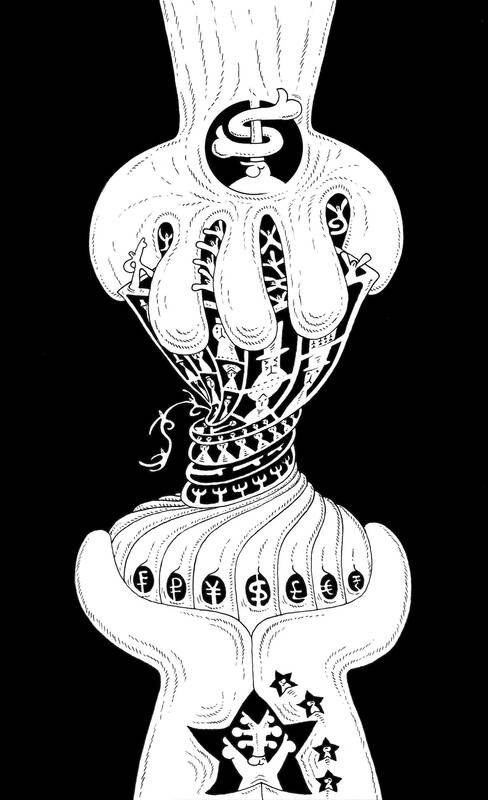

Illustration: Mountain People

He was not wrong. As then People’s Bank of China governor Zhou Xiaochuan (周小川) observed in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, global monetary stability depends on a currency issued by a sovereign state whose policies are ultimately driven by domestic priorities. The spillovers from Trump’s “America first” policies illustrate what happens when those priorities diverge from the interests of the rest of the world.

In 2009, Zhou proposed exploring a global currency decoupled from the domestic concerns of any single issuer. At the same time, he began promoting the yuan’s internationalization. Until then, China — the world’s largest exporter — had relied almost entirely on the US dollar to invoice and settle its external trade. That dependence led to a massive buildup of US dollar reserves, which peaked at US$3.8 trillion in 2014.

Reducing reliance on the US dollar and diversifying away from a single reserve asset made sense for China then, and it still does. As a large, export-driven economy, China assumes persistent risks by effectively outsourcing its payments system and savings to the US. That helps explain why Chinese holdings of US federal debt have fallen to about US$700 billion from roughly US$1.3 trillion in 2015.

Concerns about global imbalances — now back on the G7’s agenda under France’s leadership — are hardly new. They featured prominently in G20 discussions in the early 2010s, when Chinese policymakers saw a more balanced international monetary system as one that would spread adjustment burdens more evenly, reduce China’s reliance on the US dollar, and offer greater choice in payments and investments, thereby enhancing stability. The underlying rationale was straightforward: A systemically important economy like China should have a genuinely international currency.

Crucially, this vision rested on post-crisis policy cooperation through the G20. It was supported by multilateral financial institutions, particularly the IMF, which encouraged the yuan’s internationalization as a way to integrate China more fully into the global economy.

The 2016 addition of the yuan to the basket of currencies that comprise special drawing rights (the IMF’s reserve asset) was seen as a step toward a multicurrency monetary system. During China’s G20 presidency in 2016, such a shift was widely regarded as beneficial not only for China, but also for global stability.

Over the next decade that consensus largely unraveled amid rising geopolitical tensions. The prevailing view, reflected in the Center for Economic and Policy Research’s latest Geneva report, is that a multicurrency system under such conditions could deepen fragmentation and exacerbate systemic risks. Without robust coordination mechanisms, currency competition can prove destabilizing.

However, heavy dependence on the US dollar carries its own risks, especially given Trump’s erratic and often transactional policymaking. With global financial stability effectively held hostage by US domestic policies, China is developing an international currency commensurate with its growing economic footprint. The case for an international monetary system that does not hinge on a single dominant currency remains as compelling today as it was a decade ago. The path forward lies in a carefully coordinated transition toward such a system, but without policy cooperation to hold it together, instability and further fragmentation are likely to follow.

As the current chair of the G20 and the principal shareholder of both the IMF and the World Bank, the US must continue to play a leadership role. However, under Trump, the G20 risks devolving into a forum for transactional politics and division rather than multilateral cooperation, leaving it ill-equipped to manage — let alone prevent — global crises. Such an outcome would mark the end of the rules-based international economic order as we know it.

While the US retains a large influence over international finance, that concentration of power is itself a vulnerability, as global stability depends on a single player setting the rules and upholding them. Given the Trump administration’s growing willingness to flout those rules whenever they constrain its immediate interests, this arrangement can no longer be taken for granted.

That said, credible alternatives have yet to emerge. Absent a change in US policy or the emergence of a viable form of multilateralism that can function without the US, the global economy could remain plagued by uncertainty and instability.

Paola Subacchi is professor and chair in sovereign debt and finance at Sciences Po.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

In the US’ National Security Strategy (NSS) report released last month, US President Donald Trump offered his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. The “Trump Corollary,” presented on page 15, is a distinctly aggressive rebranding of the more than 200-year-old foreign policy position. Beyond reasserting the sovereignty of the western hemisphere against foreign intervention, the document centers on energy and strategic assets, and attempts to redraw the map of the geopolitical landscape more broadly. It is clear that Trump no longer sees the western hemisphere as a peaceful backyard, but rather as the frontier of a new Cold War. In particular,

When it became clear that the world was entering a new era with a radical change in the US’ global stance in US President Donald Trump’s second term, many in Taiwan were concerned about what this meant for the nation’s defense against China. Instability and disruption are dangerous. Chaos introduces unknowns. There was a sense that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) might have a point with its tendency not to trust the US. The world order is certainly changing, but concerns about the implications for Taiwan of this disruption left many blind to how the same forces might also weaken

As the new year dawns, Taiwan faces a range of external uncertainties that could impact the safety and prosperity of its people and reverberate in its politics. Here are a few key questions that could spill over into Taiwan in the year ahead. WILL THE AI BUBBLE POP? The global AI boom supported Taiwan’s significant economic expansion in 2025. Taiwan’s economy grew over 7 percent and set records for exports, imports, and trade surplus. There is a brewing debate among investors about whether the AI boom will carry forward into 2026. Skeptics warn that AI-led global equity markets are overvalued and overleveraged

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi on Monday announced that she would dissolve parliament on Friday. Although the snap election on Feb. 8 might appear to be a domestic affair, it would have real implications for Taiwan and regional security. Whether the Takaichi-led coalition can advance a stronger security policy lies in not just gaining enough seats in parliament to pass legislation, but also in a public mandate to push forward reforms to upgrade the Japanese military. As one of Taiwan’s closest neighbors, a boost in Japan’s defense capabilities would serve as a strong deterrent to China in acting unilaterally in the