For a few days, I feared the worst — a Christmas without Iberico ham.

In the buildup to the holiday, Spain, my country of birth, announced the first swine fever outbreak in more than 30 years. Within hours, the UK, where I live, responded with a blanket ban on all Spanish pork meat imports. Christmas is not Christmas for a Spanish family without a leg of jamon — think Thanksgiving without turkey. No bueno. Fortunately, I dodged the bullet: The Spain-UK restrictions have been relaxed, but many other countries, from the US to Japan, are maintaining a full prohibition.

My panic was, admittedly, a first-world problem, but it is a timely reminder that we are sleepwalking into the next pandemic. We fear something like another COVID-19 outbreak, but probably the next disease to hit the global economy will not infect humans, instead, it would be a virus that would kill a significant proportion of the domesticated animals we rely for meat, eggs, milk and other products.

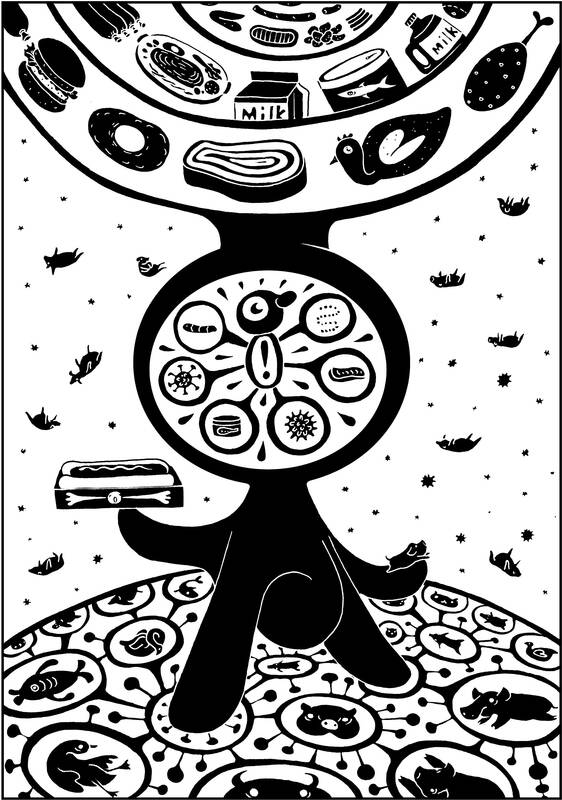

Illustration: Mountain People

We are badly prepared for such an outbreak. Yet, the warning signs are everywhere, from the rapid spread of swine fever — now affecting 50 nations — to major outbreaks of bird flu causing havoc in the egg and poultry industries of China and the US, and foot-and-mouth disease and a parasite called screwworm crippling beef supply in Europe and Central America respectively. The increase in global meat prices, which this year hit an all-time high, is closely linked to diseases.

For many veterinarians, international officials and commodity executives, a global outbreak — a panzootic — is more a question of when and how, rather than if. One statistic is particularly telling: About 75 percent of emerging infectious diseases are of animal origin. The surge in egg prices in the US to more than US$6 a dozen, up from about US$1.80 between 2010 and 2020, was, no pun intended, just an appetizer. What is potentially coming would be a lot worse. A century ago, for example the spread of the rinderpest virus killed 90 percent of all cattle in Africa.

As with COVID-19, the economic consequences would be brutal, but this time focused on food shortages and surging prices rather than furloughing workers and restricting freedom of movement. In a worst-case scenario, diets would have to change simply because to stop the plague the world would need to slaughter hundreds of millions of animals.

The problem is compounded by a series of trends that are reshaping our food consumption and agricultural supply chains beyond recognition. No one enjoys picturing the infrastructure of how meat arrives at our dining tables; herding livestock, dealing with manure, trucking animals to slaughterhouses, but that is where all the important clues lie.

The world’s diet has rapidly shifted to carnivore from vegetarian. On a per-capita basis, meat consumption nearly doubled from 1960 to this year, reaching more than 44kg a year, data compiled by the Food and Agricultural Organization shows.

The increase is exacerbated by a huge increase in global population. As a result, the world consumed about 370 million tonnes of meat last year, up from about 70 million in 1960, and everything suggests consumption would increase further. To put our new carnivorous appetite into perspective, we now consume as much beef, pork, poultry and other meat in a single decade as we did in the 30 years through the end of the 1980s.

In response to surging demand, the size of the land-based animal herd has expanded massively on the back of an often unappreciated fact: The bulk of the extra meat consumption comes from poultry. Because of the birds’ relatively small size, the rise in per-kilogram consumption translates into an outsized increase in the number of chickens bred — and killed — every year. Last year, the world slaughtered more than 85 billion land-based animals for meat — a 1,000 percent increase from 1960. The more animals, the larger the risk of diseases.

Poultry is a bloody business: Every second, we kill nearly 2,500 chickens. That is 150,000 a minute, or nearly 9 million an hour. If New York City was populated by chickens, we would kill its entire population every hour, and then repeat it 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year.

Risks are also increased by the spread of so-called factory animal farming, where thousands of animals living in close proximity create a petri dish for the expansion of diseases. Moreover, factory farming typically creates regional clusters, with many businesses near each other, further increasing the risk of the rapid spread of viruses.

Gone are the years when meat was largely eaten within national boundaries. Today, meat products, particularly the processed variety, travel internationally — and so do diseases. Take swine flu: It jumped from Africa, where it is endemic, into the Caucasus in 2007, probably via food leftovers in a ship. From there, it journeyed across eastern and western Europe.

The geography of meat production has also changed. China overtook the US as the world’s top producer in 1990; despite periodic supply shocks due to diseases, its output has continued growing. Today, China supplies more meat than the other top three nations — the US, Russia and India — combined, but China also appears to be a weak link in the global disease chain, with massive animal epidemics in the past few years. In 2018 and 2019, a large swine fever epidemic killed hundred of millions of pigs there, probably reducing economic activity by nearly 1 percentage point.

Despite the warning signs, animal health remains largely an afterthought. Few governments are spending enough on treatment, let alone prevention. Everywhere, animal health laboratories are underfunded, leading to a string of accidents that have allowed pathogens to escape. Politics plays a role: Cows, sheep, pigs and chickens do not get to vote.

The US has slashed its development aid devoted to animal disease prevention in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Earlier this year, the top food official at the UN warned that the cuts were destroying what “has taken decades to build.”

Sadly, the warning is falling on deaf ears. Ironically, the only people paying attention seem to be those promoting vegetarian diets and fighting against animal cruelty, but it is carnivores like me — and perhaps you — that have the most at stake. Let us hope we start paying attention before the first panzootic hits our beloved festive food.

Javier Blas is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. He is coauthor of The World for Sale: Money, Power and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources. This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Jan. 1 marks a decade since China repealed its one-child policy. Just 10 days before, Peng Peiyun (彭珮雲), who long oversaw the often-brutal enforcement of China’s family-planning rules, died at the age of 96, having never been held accountable for her actions. Obituaries praised Peng for being “reform-minded,” even though, in practice, she only perpetuated an utterly inhumane policy, whose consequences have barely begun to materialize. It was Vice Premier Chen Muhua (陳慕華) who first proposed the one-child policy in 1979, with the endorsement of China’s then-top leaders, Chen Yun (陳雲) and Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平), as a means of avoiding the

The last foreign delegation Nicolas Maduro met before he went to bed Friday night (January 2) was led by China’s top Latin America diplomat. “I had a pleasant meeting with Qiu Xiaoqi (邱小琪), Special Envoy of President Xi Jinping (習近平),” Venezuela’s soon-to-be ex-president tweeted on Telegram, “and we reaffirmed our commitment to the strategic relationship that is progressing and strengthening in various areas for building a multipolar world of development and peace.” Judging by how minutely the Central Intelligence Agency was monitoring Maduro’s every move on Friday, President Trump himself was certainly aware of Maduro’s felicitations to his Chinese guest. Just

A recent piece of international news has drawn surprisingly little attention, yet it deserves far closer scrutiny. German industrial heavyweight Siemens Mobility has reportedly outmaneuvered long-entrenched Chinese competitors in Southeast Asian infrastructure to secure a strategic partnership with Vietnam’s largest private conglomerate, Vingroup. The agreement positions Siemens to participate in the construction of a high-speed rail link between Hanoi and Ha Long Bay. German media were blunt in their assessment: This was not merely a commercial win, but has symbolic significance in “reshaping geopolitical influence.” At first glance, this might look like a routine outcome of corporate bidding. However, placed in

China often describes itself as the natural leader of the global south: a power that respects sovereignty, rejects coercion and offers developing countries an alternative to Western pressure. For years, Venezuela was held up — implicitly and sometimes explicitly — as proof that this model worked. Today, Venezuela is exposing the limits of that claim. Beijing’s response to the latest crisis in Venezuela has been striking not only for its content, but for its tone. Chinese officials have abandoned their usual restrained diplomatic phrasing and adopted language that is unusually direct by Beijing’s standards. The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs described the