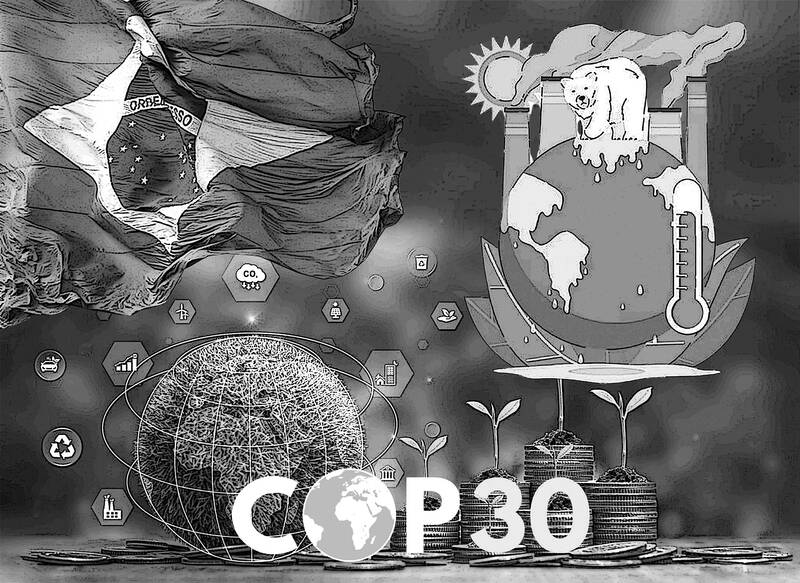

This year’s UN Climate Change Conference (COP30) in Brazil comes at a decisive moment, not just for the climate agenda, but for international cooperation more broadly. Following last year’s “finance COP” in Baku — where countries agreed to triple the global target for climate finance — this year’s gathering is being framed as the “implementation COP.”

After years of negotiations, the time for ambitious commitments has passed. We now need concrete action. That means actually mobilizing climate finance, not as an act of charity, but as a strategic investment in global resilience, shared prosperity and mutual security.

Developing countries are not coming to the table empty-handed. They are bringing ambitious climate plans, national commitments and domestic financing of their own. Bangladesh, for example, draws 75 percent of its climate finance from its own resources and allocates 6 percent to 7 percent of its annual budget to climate-related efforts.

Illustration: Constance Chou

Many developing countries are also submitting updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC, the Paris Agreement’s term for emissions reduction plans), strengthening their policy frameworks and pioneering locally driven solutions that can inform global best practices. Bangladesh recently submitted its “NDC 3.0,” which sets an unconditional emissions reduction target of 6.39 percent by 2035 (in the business-as-usual scenario) and a conditional target of 13.92 percent.

However, the total investment required to implement Bangladesh’s NDC is a staggering US$116 billion. That is why it has created the Bangladesh Climate and Development Platform (BCDP), a nationally owned mechanism designed to scale up climate finance and integrate national climate strategies. With strong political support, the BCDP brings together more than 10 ministries, marking a significant milestone in coordinated, country-led climate action.

As a coastal country, Bangladesh is home to some of the world’s most fragile ecosystems, including the Sundarbans mangrove forest and the world’s largest river delta. These ecosystems provide essential services such as climate regulation, carbon sequestration and disaster risk reduction. Protecting them is vital not only for Bangladesh, but also for the planet. However, doing so requires international support.

The same message applies across the global south. While developing countries are stepping up, their plans require external support. The COP29 commitment to mobilize US$300 billion per year in international climate finance starting next year must be the baseline. This figure still represents only a small fraction of what is needed, and we still need to ensure that financing is managed with a higher level of accountability. Developed countries must be held to their commitments, so that new funding is truly additional, rather than being repurposed from existing development aid.

Another priority concerns the quality of financing, which must be well structured, accessible and effective. That means clarifying how much each developed country will contribute; how resources will be balanced between mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage; and how delivery will be made predictable and fair.

Loans that push developing countries further into debt are not sustainable. A much larger share of finance must come in the form of grants and highly concessional flows. The world cannot build climate resilience on the back of fiscal instability. This was already a recurring theme in Baku, and now COP30 gives us a chance to translate it into a clear policy framework.

Climate finance is sound economics, representing opportunity, not just obligation.

Studies showed that every US$1 invested in adaptation can generate more than US$10 in long-term benefits. For developed countries, supporting adaptation and resilience abroad helps stabilize supply chains, reduce disaster risks and prevent crises that would spill over borders.

At the same time, developing countries hold vast, often untapped, potential to drive the global energy transition, safeguard food systems and power sustainable growth. Bangladesh, for example, is the world’s third-largest rice producer. Helping it achieve resilience against climate shocks is critical for domestic and global food security. It also contributes to global value chains through seafood, textiles and a dynamic, skilled workforce. With young people comprising 28 percent of its population, Bangladesh has the potential to be a key partner in many growth industries of the future.

As an investment in our shared future, climate finance requires partnerships that would benefit everyone — economically, socially and environmentally. Merely increasing our financing targets is not enough. Developing countries last year engaged in good faith to reach an agreement on climate finance, even though the outcome did not fully reflect our needs. That commitment to dialogue must now be matched by a commitment to clarity and delivery. We need all countries to engage constructively in shaping the structure of climate finance. The question is not just how much, but how it flows and how it can best be used to drive long-term transformations.

Already, Brazil and Azerbaijan are coleading efforts to build a roadmap to scale climate finance to US$1.3 trillion annually by 2035. However, we cannot reach that goal without laying the foundation for it. That means delivering the promised US$300 billion per year through mechanisms that are transparent, fair and effective.

With multilateralism in crisis, we must restore faith in the process. Multilateralism has delivered before, and it can do so again. COP30 is where we can prove that the international system is capable of moving from commitment to implementation, and from division to cooperation. We have the tools, and we have the knowledge. What we need now is the will to turn climate finance into a shared engine for growth, security and a fairer future.

Syeda Rizwana Hasan is adviser for environment, forest and climate change of Bangladesh.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Donald Trump’s return to the White House has offered Taiwan a paradoxical mix of reassurance and risk. Trump’s visceral hostility toward China could reinforce deterrence in the Taiwan Strait. Yet his disdain for alliances and penchant for transactional bargaining threaten to erode what Taiwan needs most: a reliable US commitment. Taiwan’s security depends less on US power than on US reliability, but Trump is undermining the latter. Deterrence without credibility is a hollow shield. Trump’s China policy in his second term has oscillated wildly between confrontation and conciliation. One day, he threatens Beijing with “massive” tariffs and calls China America’s “greatest geopolitical

US President Donald Trump’s seemingly throwaway “Taiwan is Taiwan” statement has been appearing in headlines all over the media. Although it appears to have been made in passing, the comment nevertheless reveals something about Trump’s views and his understanding of Taiwan’s situation. In line with the Taiwan Relations Act, the US and Taiwan enjoy unofficial, but close economic, cultural and national defense ties. They lack official diplomatic relations, but maintain a partnership based on shared democratic values and strategic alignment. Excluding China, Taiwan maintains a level of diplomatic relations, official or otherwise, with many nations worldwide. It can be said that

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairwoman Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) made the astonishing assertion during an interview with Germany’s Deutsche Welle, published on Friday last week, that Russian President Vladimir Putin is not a dictator. She also essentially absolved Putin of blame for initiating the war in Ukraine. Commentators have since listed the reasons that Cheng’s assertion was not only absurd, but bordered on dangerous. Her claim is certainly absurd to the extent that there is no need to discuss the substance of it: It would be far more useful to assess what drove her to make the point and stick so

The central bank has launched a redesign of the New Taiwan dollar banknotes, prompting questions from Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — “Are we not promoting digital payments? Why spend NT$5 billion on a redesign?” Many assume that cash will disappear in the digital age, but they forget that it represents the ultimate trust in the system. Banknotes do not become obsolete, they do not crash, they cannot be frozen and they leave no record of transactions. They remain the cleanest means of exchange in a free society. In a fully digitized world, every purchase, donation and action leaves behind data.