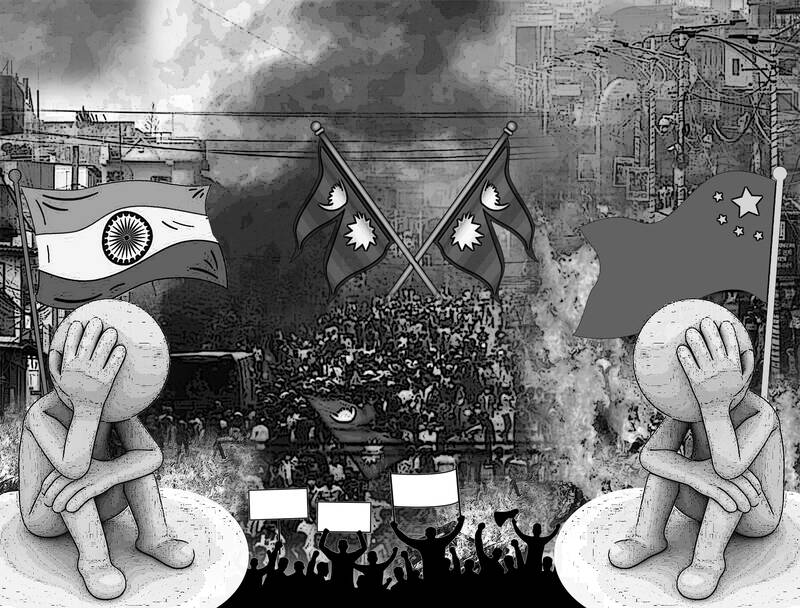

A new political generation is reshaping Nepal’s future. For decades, the Himalayan nation has been caught between India and China, both vying for influence through patronage and investment, but those familiar formulas might no longer work.

Nepal’s location has long made it a geopolitical prize for New Delhi and Beijing. Landlocked between the two, it has been the object of endless courtship, but also manipulation. Successive governments have often tilted toward one giant neighbor or the other, but the nation’s deepest political crisis in years is disrupting that playbook.

Cities across the country were scenes of chaos last week. Young and angry protesters ransacked and burned down government buildings, including the parliament. The immediate catalyst for their rage was a short-lived social media ban imposed by Nepalese Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli’s government, but grievances run much deeper. This generation is fed up with what it views as endemic corruption and a lack of economic opportunities in a nation run by long-entrenched elites.

Illustration: Constance Chou

Oli resigned and the former Supreme Court chief justice Sushila Karki was sworn in as interim leader, the nation’s first female prime minister.

Both India and China were quick to congratulate her, but have refrained from commenting further.

Patience is wise. There is nothing to gain by meddling at a time of instability.

India and Nepal are bound by trade, geography and history. The two share South Asia’s only truly open border, with visa-free movement and deep people-to-people ties. Political goodwill with Kathmandu is crucial for Indian security, with New Delhi wary of cross-border drug flows, terrorism and other threats. Nearly all of Nepal’s third-country trade and gasoline supplies flow through India, which also provides significant development aid.

New Delhi should not mistake proximity for power. This generation of Nepalese do not feel unduly indebted to their more powerful neighbor. Instead, their memories are laced with resentment. India’s 2015 blockade, which resulted in huge shortages of fuel and medicine, despite conflicting accounts on both sides over who was responsible, is just one example.

India’s missteps were a boon for China, which has positioned Kathmandu as a critical link in its massive overseas infrastructure investment program, the Belt and Road Initiative. A shared border is also critical for Beijing because of Tibet, which it annexed in the 1950s. Beijing is particularly sensitive to more Tibetan refugees in Nepal, as its worried about any threat to its claims to the autonomous region.

To extend its influence, China has been investing in projects such as road construction, tunnel development, hydropower and communications initiatives. The strategy appeared to be working, up until this latest bout of political turmoil at least. In December last year, in a break from tradition when newly appointed leaders typically go to India on their first state visit, Oli made a four-day trip to China.

These tactics will not work with a generation fed up with the old power structures and a flagging economy. Youth unemployment is estimated at about 20 percent, while Transparency International consistently ranks Nepal poorly — it is no surprise that young people feel the system is stacked against them.

If India and China continue treating Nepal primarily as a geopolitical pawn, they risk alienating future leaders. They need to understand the new power brokers would require a different approach, said Puspa Sharma, a visiting senior research fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore.

“They should remain disengaged in the political discourse,” Sharma said. “Instead, focus on aid, reconstruction, any kind of job-related support they can provide.”

Stepping back from political meddling and focusing on tangible benefits would be prudent. New Delhi could lean into its traditional advantages, and continue with uninterrupted fuel and food flows. It could also offer more youth apprenticeships and exchange programs, and speak directly to the kinds of issues that this generation of Nepalese say are important.

Beijing could offer smaller job-rich projects, to deflect criticism that its infrastructure program is exploitative. It could also align scholarships in sectors young people want, such as technology, medicine and renewable energy.

Nepal’s immediate task is to prevent the political dynamism from turning into prolonged chaos. This new generation needs stability, jobs and accountability. For India and China, the temptation to interfere is strong, but restraint is far more productive.

Karishma Vaswani is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asia politics with a special focus on China. Previously, she was the BBC’s lead Asia presenter and worked for the BBC across Asia and South Asia for two decades. This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

On Sept. 3 in Tiananmen Square, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) rolled out a parade of new weapons in PLA service that threaten Taiwan — some of that Taiwan is addressing with added and new military investments and some of which it cannot, having to rely on the initiative of allies like the United States. The CCP’s goal of replacing US leadership on the global stage was advanced by the military parade, but also by China hosting in Tianjin an August 31-Sept. 1 summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which since 2001 has specialized

In an article published by the Harvard Kennedy School, renowned historian of modern China Rana Mitter used a structured question-and-answer format to deepen the understanding of the relationship between Taiwan and China. Mitter highlights the differences between the repressive and authoritarian People’s Republic of China and the vibrant democracy that exists in Taiwan, saying that Taiwan and China “have had an interconnected relationship that has been both close and contentious at times.” However, his description of the history — before and after 1945 — contains significant flaws. First, he writes that “Taiwan was always broadly regarded by the imperial dynasties of

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will stop at nothing to weaken Taiwan’s sovereignty, going as far as to create complete falsehoods. That the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has never ruled Taiwan is an objective fact. To refute this, Beijing has tried to assert “jurisdiction” over Taiwan, pointing to its military exercises around the nation as “proof.” That is an outright lie: If the PRC had jurisdiction over Taiwan, it could simply have issued decrees. Instead, it needs to perform a show of force around the nation to demonstrate its fantasy. Its actions prove the exact opposite of its assertions. A

A large part of the discourse about Taiwan as a sovereign, independent nation has centered on conventions of international law and international agreements between outside powers — such as between the US, UK, Russia, the Republic of China (ROC) and Japan at the end of World War II, and between the US and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) since recognition of the PRC as the sole representative of China at the UN. Internationally, the narrative on the PRC and Taiwan has changed considerably since the days of the first term of former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) of the Democratic