It is not just people who struggle to perform effectively when the temperature starts to soar. The electricity system we depend on to keep us cool is having the same problem.

A swarm of jellyfish linked to unusually warm waters in northern Europe caused French utility Electricite de France to shut two nuclear power stations last week, after the invertebrates clogged up parts of their cooling systems. Other reactors in the country might have to cut output because temperatures in the Rhone and Garonne rivers are too high.

In Iraq, supply to most of the country went down on Monday last week as millions of Shiite pilgrims descended on Karbala for Arba’in, spiking grid demand for fans and air-conditioners as the mercury rose above 40°C.

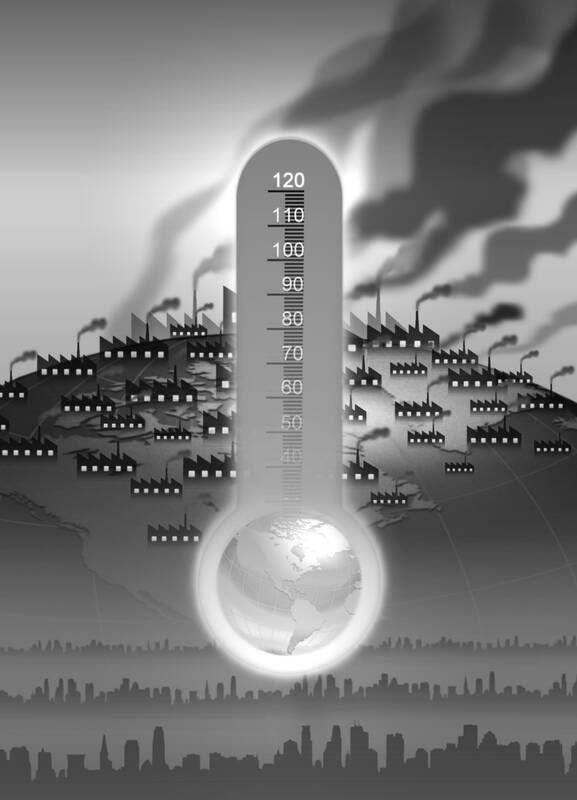

Illustration: Yusha

Even backup equipment struggles in such conditions: With the heat rising into the 30s, electricity went out and play was suspended at the Cincinnati Open tennis tournament on Tuesday last week, after an on-site generator apparently overheated.

Power that goes out when it is most needed should infuriate and frustrate but not surprise us. Most infrastructure was designed to perform within specific temperature ranges that the global climate is rapidly leaving behind. More of it is likely to start breaking as heat waves become more intense and widespread.

That is particularly the case with thermal generators — those that use the heat from burning fuels or atomic decay to spin turbines and induce electrical charges. Such plants have to find a way to dump excess heat, but that gets harder as the air and water outside warm up. The result is decreasing efficiency and overheating, forcing the plants to burn more fuel for the same output, or even halt operations altogether.

The effects can be significant. The probability that a coal generator would have a forced outage goes up by 3.2 percentage points during heat waves, while gas and nuclear are respectively 1.3 and 1 percentage points more likely to suffer an unplanned failure, a study by researchers in Sweden and Italy showed.

Separately, Iraqi researchers found that a gas plant lost about 21 percent of its generation potential as the temperature rose from 25°C to 50°C.

Drought, which commonly occurs alongside heat waves, makes the problem worse. Most thermal generators cool themselves by heating up water, whether it is in the sea, rivers or cooling towers. Cool water, like cool air, gets less abundant as the temperature rises.

India has lost 19 days’ worth of coal electricity since 2014 because water shortages have forced shutdowns, Reuters reported. In many areas, residents depend on tanker trucks and ever-deeper boreholes because generators are using up all of the surface water. Power stations might put more pressure on water supplies between now and 2050 than the drinking water needs of its population, government forecasts showed.

Conventional generators are not the only ones to suffer. As anyone who has sat through a still, sticky summer day would recognize, wind speeds often plummet in hot weather. Since the early 1980s, the area of the globe affected by such conditions has increased by 6.3 percent every decade, to the point that about 60 percent of the planet is at risk.

In Australia, Siberia and Europe, the availability of wind can decline by 30 to 50 percent during heat waves relative to what it would be in normal years — although a few areas, such as the northern US, east Africa, the Amazon and western China, experience the opposite effect.

Even if we can solve the problem of generating energy, getting it to consumers presents challenges. Transmission cables and transformers heat up as electrons travel through their wires, and rising air temperatures make such components more susceptible to failure — especially as they are typically working harder on such days due to all the air-conditioners and fans running.

It is not just people who need relief from the heat. About one-third of electricity consumption from data centers comes from heating and cooling to maintain stable temperatures on-site. That demand rises along with the mercury, and is becoming more pressing with the spread of artificial intelligence and cryptocurrencies.

A heat wave in 2022 caused chaos at two London hospitals when their server racks shut down, scrambling the information technology systems they depend on to process medical data.

The rising dominance of solar panels and lithium-ion batteries, which tend to be more resilient than thermal generators and wind during heat waves, offer some respite. It still might not be enough. Most of industrial civilization, built from the energy riches unleashed by coal, oil and gas, depends on a moderate climate that their carbon emissions are throwing into disorder. The damage caused by fossil technology is going to be with us long after we have switched to cleaner ways of generating power.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering climate change and energy. Previously, he worked for Bloomberg News, the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times. This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

The image was oddly quiet. No speeches, no flags, no dramatic announcements — just a Chinese cargo ship cutting through arctic ice and arriving in Britain in October. The Istanbul Bridge completed a journey that once existed only in theory, shaving weeks off traditional shipping routes. On paper, it was a story about efficiency. In strategic terms, it was about timing. Much like politics, arriving early matters. Especially when the route, the rules and the traffic are still undefined. For years, global politics has trained us to watch the loud moments: warships in the Taiwan Strait, sanctions announced at news conferences, leaders trading

Eighty-seven percent of Taiwan’s energy supply this year came from burning fossil fuels, with more than 47 percent of that from gas-fired power generation. The figures attracted international attention since they were in October published in a Reuters report, which highlighted the fragility and structural challenges of Taiwan’s energy sector, accumulated through long-standing policy choices. The nation’s overreliance on natural gas is proving unstable and inadequate. The rising use of natural gas does not project an image of a Taiwan committed to a green energy transition; rather, it seems that Taiwan is attempting to patch up structural gaps in lieu of

The saga of Sarah Dzafce, the disgraced former Miss Finland, is far more significant than a mere beauty pageant controversy. It serves as a potent and painful contemporary lesson in global cultural ethics and the absolute necessity of racial respect. Her public career was instantly pulverized not by a lapse in judgement, but by a deliberate act of racial hostility, the flames of which swiftly encircled the globe. The offensive action was simple, yet profoundly provocative: a 15-second video in which Dzafce performed the infamous “slanted eyes” gesture — a crude, historically loaded caricature of East Asian features used in Western

The Executive Yuan and the Presidential Office on Monday announced that they would not countersign or promulgate the amendments to the Act Governing the Allocation of Government Revenues and Expenditures (財政收支劃分法) passed by the Legislative Yuan — a first in the nation’s history and the ultimate measure the central government could take to counter what it called an unconstitutional legislation. Since taking office last year, the legislature — dominated by the opposition alliance of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party — has passed or proposed a slew of legislation that has stirred controversy and debate, such as extending