As much of Europe bakes in a heat wave — which has led to power cuts, deaths and wildfires — you would think that the case for ambitious emissions cuts would be easy to make.

Not quite. The European Commission’s 2040 climate target has stuck to its climate change advisory board’s recommendation of a 90 percent decline in greenhouse gas emissions compared with 1990 levels, which is welcome. However, under pressure from member states including Poland, Italy and France, it was only able to make that politically palatable with the addition of what the commission is calling “flexibilities” and critics are calling “loopholes.” It is a clear sign that the geopolitical context — and the EU’s approach to the environment — has changed.

The proposal allows for the use of international carbon credits — typically purchased from poorer, more vulnerable countries — to make up 3 percent of emissions reductions from 2036 onward. In other words, it enables the EU to outsource climate action, and it is the first time the bloc has set a climate target that is not wholly dependent on domestic progress.

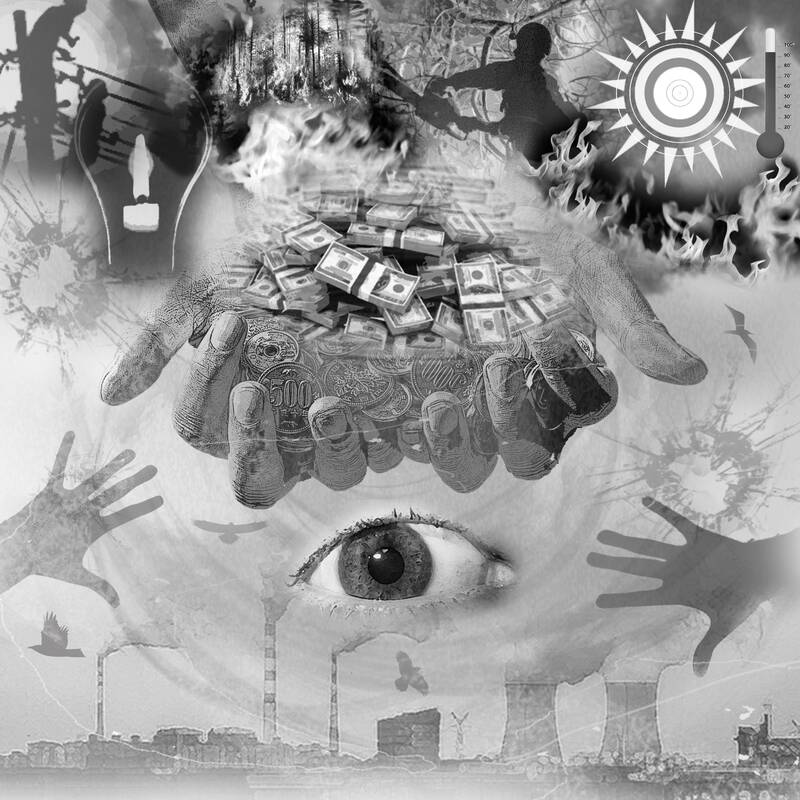

Illustration: Kevin Sheu

There are reasonable arguments for including the caveat. In theory, it could serve as a mechanism to funnel funds into countries that find it hard to access essential climate finance. Some nations are already doing it: Switzerland bought carbon offsets that funded the rollout of electric buses in Thailand. It is cheaper to electrify public transport in Bangkok than it is in Bern, but on paper the emissions reductions are the same, so why not? The problem is that offsets have a long history of not doing what they claim to. Critics, including the EU’s own scientific advisory board, argue that it could “undermine” efforts to reduce emissions in richer countries. To maintain the integrity of the EU’s progress on emissions, the allowance needs to come with some strict rules regarding quality and the types of activities that qualify — and a way to properly enforce those standards.

Despite the controversy, it is unlikely that a big fight would happen over the proposal, which is the result of intensive consultations behind the scenes. The EU needs to get this tidied away so it can inform the 2035 nationally determined contribution (NDC) required by the UN, which is already months overdue. To have any sway at the next climate conference in Brazil, the NDC needs to be submitted by September.

The real battle of wills would likely focus on the simplification agenda striking a number of key green regulations, including reporting rules, agriculture and finance. These so-called omnibus packages are part of a broader pattern of backtracking on European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s flagship Green Deal introduced in 2019.

Between wolves getting their protection status downgraded, delays to anti-deforestation regulation and electric vehicle targets, and attacks on the nature restoration law, it is hard to shake the feeling that the EU is losing its grip on climate leadership.

The pressure to dilute green ambitions stems from the rise of right-wing populist politicians across the bloc. Even French President Emmanuel Macron, once a staunch defender of climate action on the world stage, has allowed multiple environmental policies to collapse in France, including the introduction of low-emission zones. He was one of the voices pushing to delay agreement on the 2040 target, arguing that it has to be “compatible with our competitiveness.”

The Green Deal was introduced to a continent unshaken by a pandemic and war, so in some ways it is understandable that defense and enterprise have grown in importance. However, backtracking comes with its own costs for businesses.

On July 1, a joint letter was published, urging the EU to preserve its sustainable finance plans. Signed by more than 150 businesses and investors, including French energy multinational EDF SA, global insurer and asset manager Allianz SE and France’s La Banque Postale Asset Management, the statement said that sustainability rules are “conducive to competitiveness and growth, as well as long-term value creation and subsequent returns for investors.”

What Europeans need more than anything is a clear and stable environment so they can plan for the future. The omnibus initiatives could help that by providing clarity where the laws are currently confusing, but it would be a big mistake to dilute the EU’s green ambition any more than it already has.

Lara Williams is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering climate change. This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

We are used to hearing that whenever something happens, it means Taiwan is about to fall to China. Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) cannot change the color of his socks without China experts claiming it means an invasion is imminent. So, it is no surprise that what happened in Venezuela over the weekend triggered the knee-jerk reaction of saying that Taiwan is next. That is not an opinion on whether US President Donald Trump was right to remove Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro the way he did or if it is good for Venezuela and the world. There are other, more qualified

The immediate response in Taiwan to the extraction of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro by the US over the weekend was to say that it was an example of violence by a major power against a smaller nation and that, as such, it gave Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) carte blanche to invade Taiwan. That assessment is vastly oversimplistic and, on more sober reflection, likely incorrect. Generally speaking, there are three basic interpretations from commentators in Taiwan. The first is that the US is no longer interested in what is happening beyond its own backyard, and no longer preoccupied with regions in other

As technological change sweeps across the world, the focus of education has undergone an inevitable shift toward artificial intelligence (AI) and digital learning. However, the HundrED Global Collection 2026 report has a message that Taiwanese society and education policymakers would do well to reflect on. In the age of AI, the scarcest resource in education is not advanced computing power, but people; and the most urgent global educational crisis is not technological backwardness, but teacher well-being and retention. Covering 52 countries, the report from HundrED, a Finnish nonprofit that reviews and compiles innovative solutions in education from around the world, highlights a

Jan. 1 marks a decade since China repealed its one-child policy. Just 10 days before, Peng Peiyun (彭珮雲), who long oversaw the often-brutal enforcement of China’s family-planning rules, died at the age of 96, having never been held accountable for her actions. Obituaries praised Peng for being “reform-minded,” even though, in practice, she only perpetuated an utterly inhumane policy, whose consequences have barely begun to materialize. It was Vice Premier Chen Muhua (陳慕華) who first proposed the one-child policy in 1979, with the endorsement of China’s then-top leaders, Chen Yun (陳雲) and Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平), as a means of avoiding the