If it was not for the Arolsen Archives, half-sisters Sula Miller and Helen Schaller would never have met. American Miller and German Schaller only recently discovered they had the same father — a Holocaust survivor who emigrated to the US.

Miller “contacted us because she was looking for information about her father,” said Floriane Azoulay, director of the Arolsen Archives, the world’s largest repository of information on the victims and survivors of the Nazi regime.

Mendel Mueller, a Jew born in the Austro-Hungarian empire, was incarcerated in two Nazi concentration camps: Buchenwald in northern Germany and Auschwitz in what was then occupied Poland.

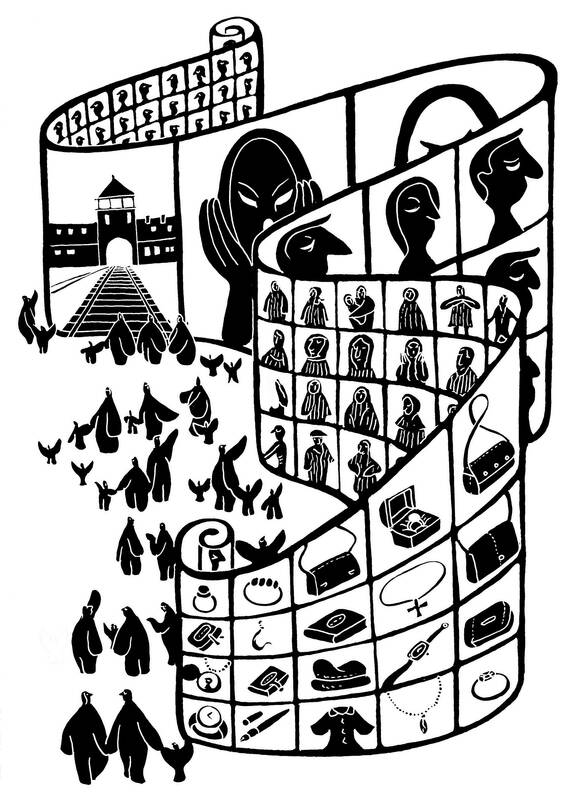

Illustration: Mountain People

An investigation of the archives revealed he had another daughter, Schaller, who was still alive and living in Germany.

“Thanks to us, the two women got to know each other,” Azoulay said.

Eighty years after the end of World War II, people all over the world are still discovering the fate of their family members sent to Adolf Hitler’s Nazi death camps.

The vast Arolsen Archives in the quaint spa town of Bad Arolsen in central Germany contain millions of documents and objects.

When Miller contacted the archive to find out about her father, researchers stumbled upon a 1951 letter from his wife looking for his whereabouts.

Shortly after the war, Mueller had married a German woman — the mother of his daughter Schaller, born in 1947, but later he left for the US without her and started a new life there, marrying an Austrian woman — who gave birth to Miller in 1960.

Four years after Miller’s initial inquiry, investigators from Bad Arolsen tracked Schaller down and the two sisters met for the first time last year.

“Their physical resemblance was striking,” Azoulay said.

The two had complicated and conflicting views on their father, but “their meeting helped them make peace with the past,” she said.

Although 90 percent of the material held by the Arolsen Archive has now been digitized, the complex still stores about 30 million original documents on almost 17.5 million people.

There are also thousands of items such as watches, rings and wallets collected from the old Nazi camps.

The archive was originally set up by the Allies in early 1946 as the International Tracing Service to help people find relatives who had disappeared during the war.

It mostly dealt with Jews, but also Roma, homosexuals, political dissidents and “racially pure” children kidnapped by the Nazis as part of a program to address the falling birthrate.

ORIGINS

Bad Arolsen was chosen because it had escaped Allied bombing and had a working telephone network, and because of its location at the center of Germany’s four occupation zones — French, US, British and Soviet.

At first the service was run by a curious mix of members of the Allied forces, Holocaust survivors from all over Europe and Germans — including former members of the Nazi party, but from the 1950s onward, as many of the survivors left the country, German staff numbers increased.

Today, the archive has about 200 employees, assisted by about 50 volunteers around the world.

It is still handling about 20,000 inquiries per year, Azoulay said, often from children or grandchildren of victims or survivors who want to know what happened to them.

Like Abraham Ben, born to Polish-Jewish parents in a displaced-persons camp in Bamberg, southern Germany, in May 1947.

Now almost 80, Ben is still hoping to shed light on the fate of his father’s family, who were left behind when he escaped from the Warsaw Ghetto.

“There is a high probability that they died in the camps,” he said.

Ben’s father “never talked about [the Holocaust] ... and we never asked him about it. We felt it was too painful for him,” he said.

Almost no one had grandparents in the center for Jewish refugees where Ben was born because elderly people — too weak to work — were first to be killed in the camps.

“At the age of 10, I realized other children had grandparents because I went to a German school and my classmates would describe the gifts they had given them at Christmas,” Ben said.

He is hoping to find “cousins who might have survived” among the children of his father’s five brothers and sisters, he added.

The archives at Bad Arolsen include documents issued by the Nazi party, such as Gestapo arrest warrants, lists of people to be transported to the camps and camp registers.

The documents are often surprisingly detailed, given the low chances of survival of the people listed in them.

In Buchenwald, the camp register kept a record of every prisoner’s height, eye and hair color, facial features, marital status, children, religion and which languages they spoke, as well as their name, date of birth and deportation number.

NAME ISSUES

From the beginning, the records were sorted according to a phonetic alphabet, as the same name can be spelled differently in different languages.

“For example, there are more than 800 ways to write ‘Abrahamovicz,’” said Nicole Dominicus, head of archive administration.

Later the archives were expanded to include files compiled by the Allies, as well as correspondence between the Red Cross and the Nazi administration.

The files also contain letters written by people searching for their lost relatives.

In a letter written to the International Tracing Service in 1948, a mother who survived Auschwitz asks about her missing daughter, who she was separated from in the camp.

Volunteers working for the archives outside Germany also help trawl through records in other countries.

Manuela Golc, a volunteer in Poland, recently met a 93-year-old woman to hand over a pair of earrings and a watch that had belonged to her mother, who was deported in 1944 after the Warsaw Uprising.

“She told me it was the best day of her life,” said Golc, with tears in her eyes.

German Achim Werner, 58, was “shocked” when the archives contacted him to let him know they had his grandfather’s wedding ring, taken from him when he arrived at the Dachau concentration camp. Werner had visited the camp near Munich several times, on school excursions and as an adult, without knowing that his grandfather had been held there.

“We knew that he was detained in 1940, but nothing after that,” he said.

Werner does not know why his grandfather was imprisoned and as the archives have no further information about him, he probably never will, but he wants to keep the man’s memory alive and has given the wedding ring to his daughter.

“She will wear it as a pendant and then pass it on to her children,” he said.

When US budget carrier Southwest Airlines last week announced a new partnership with China Airlines, Southwest’s social media were filled with comments from travelers excited by the new opportunity to visit China. Of course, China Airlines is not based in China, but in Taiwan, and the new partnership connects Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport with 30 cities across the US. At a time when China is increasing efforts on all fronts to falsely label Taiwan as “China” in all arenas, Taiwan does itself no favors by having its flagship carrier named China Airlines. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is eager to jump at

The muting of the line “I’m from Taiwan” (我台灣來欸), sung in Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), during a performance at the closing ceremony of the World Masters Games in New Taipei City on May 31 has sparked a public outcry. The lyric from the well-known song All Eyes on Me (世界都看見) — originally written and performed by Taiwanese hip-hop group Nine One One (玖壹壹) — was muted twice, while the subtitles on the screen showed an alternate line, “we come here together” (阮作伙來欸), which was not sung. The song, performed at the ceremony by a cheerleading group, was the theme

Secretary of State Marco Rubio raised eyebrows recently when he declared the era of American unipolarity over. He described America’s unrivaled dominance of the international system as an anomaly that was created by the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War. Now, he observed, the United States was returning to a more multipolar world where there are great powers in different parts of the planet. He pointed to China and Russia, as well as “rogue states like Iran and North Korea” as examples of countries the United States must contend with. This all begs the question:

In China, competition is fierce, and in many cases suppliers do not get paid on time. Rather than improving, the situation appears to be deteriorating. BYD Co, the world’s largest electric vehicle manufacturer by production volume, has gained notoriety for its harsh treatment of suppliers, raising concerns about the long-term sustainability. The case also highlights the decline of China’s business environment, and the growing risk of a cascading wave of corporate failures. BYD generally does not follow China’s Negotiable Instruments Law when settling payments with suppliers. Instead the company has created its own proprietary supply chain finance system called the “D-chain,” through which