Artificial intelligence (AI) is often presented as the next peak of human innovation, owing to its potential to revolutionize industries, transform economies and improve lives. However, would AI truly benefit everyone or would it deepen existing divides? The answer depends on how the technology is developed, deployed and governed. Without purposeful interventions, AI’s potential would be harnessed for narrow gains by those who prioritize profits over people.

Encouragingly, the cost of AI development is beginning to decline. While OpenAI’s GPT-4 costs US$100 million to train, the Chinese start-up DeepSeek’s comparable model apparently costs a fraction of that. That trend has promising implications for developing countries, which generally lack the massive financial resources that earlier AI innovations required, but could soon be able to access and leverage those technologies more affordably. The choices we make today would determine whether AI becomes an instrument of inclusion or exclusion.

To ensure that AI serves humanity, we need to focus on incentives. AI development today is largely dictated by market forces, with an excessive focus on automation and monetizing personal data. The few countries spearheading AI technologies are investing billions of dollars in labor-replacing applications that would exacerbate inequality. Making matters worse, government subsidies frequently focus on technical merits, which often target efficiency, without sufficient consideration of their direct and indirect societal impact.

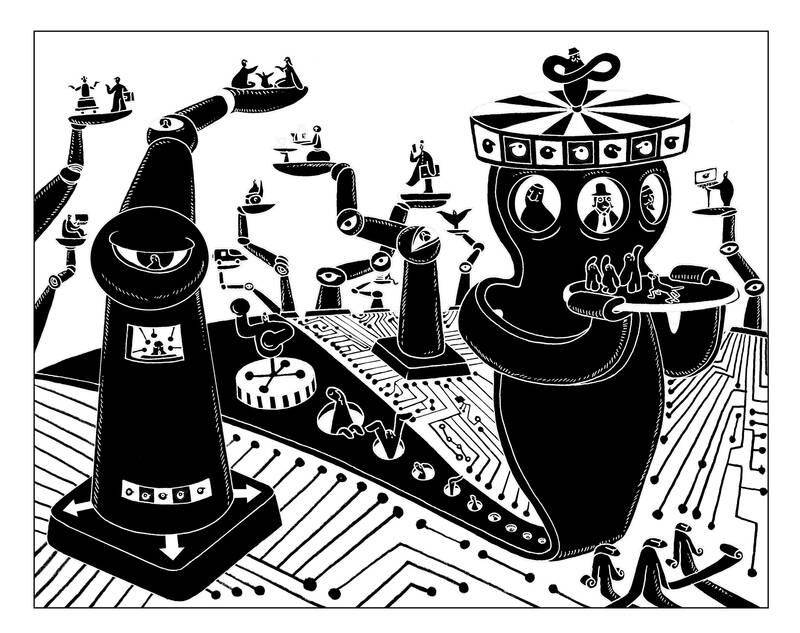

Illustration: Mountain People

Where jobs disappear, economic, social and political instability tend to follow. Yet public funding continues to flow toward automation. Governments must realign incentives to encourage AI that serves social needs, such as enhancing education, improving health outcomes and tackling climate challenges. AI should empower, not replace, human workers. Population aging is a major challenge in some countries. Although household robots might help address some of the problems of an aging population, the frontier of current development focuses on priorities such as dynamic performance (running, jumping or obstacle avoidance) in outdoor environments, rather than functions centering on safety and practicality, daily living assistance or chronic disease management.

The task cannot be left to venture capital alone, which funneled US$131.5 billion into start-ups last year, largely chasing overhyped and speculative technologies such as artificial general intelligence. Narrower-purpose models can advance medical diagnostics, assist radiologists, predict natural disasters and much more. Redirecting investments toward solutions that directly benefit society is essential to keeping AI development aligned with collective progress, rather than shareholder value.

It is also necessary to bridge the divide between developed and developing economies. AI’s transformative potential remains largely untapped in low and middle-income countries, where inadequate infrastructure, limited skills and resource constraints hinder adoption. Left unaddressed, that technological divide would only widen global inequalities.

Consider what AI could do just for healthcare. It could broaden access to personalized medicine, giving patients in resource-limited settings tailored treatments with greater efficacy and fewer adverse effects. It could assist in diagnosis, by helping doctors detect diseases earlier and more accurately. And it could improve medical education, using adaptive learning and real-time feedback to train medical professionals in underserved areas.

More broadly, AI-powered adaptive learning systems are already customizing educational content to meet individual needs and bridge knowledge gaps. AI tutoring systems offer personalized instruction that increases engagement and improves outcomes. By making it far easier to learn a new language and acquire new skills, technology could drive a massive expansion of economic opportunities, particularly for marginalized communities.

Nor are the uses confined to healthcare and education. The University of Oxford’s Inclusive Digital Model demonstrates that equipping marginalized groups — especially women and young people — with digital skills allow them to participate in the global digital economy, reducing income disparities.

However, global cooperation is crucial to unlock those benefits. AI must be approached collectively, such as through south-south initiatives to create solutions tailored to developing countries’ circumstances and needs. By fostering partnerships and knowledge-sharing, lower and middle-income countries can bridge the technological divide and ensure that AI serves a broad range of constituencies beyond the dominant players.

Then there is the question of safety and ethical use. Those issues must also be addressed globally. Without robust ethical frameworks, AI can be — and has already been — used for harmful purposes, from mass surveillance to the spread of misinformation.

The international community would need to agree on shared principles to ensure that AI is used consistently and responsibly. The UN — through inclusive platforms such as the UN Commission on Science and Technology for Development — can help shape global regulations. The top priorities should be transparency (ensuring that AI decisionmaking is discernible and explainable), data sovereignty (protecting individuals’ and countries’ control over their own data), harm prevention (prohibiting applications that undermine human rights) and equitable access. Multilateral initiatives to develop digital infrastructure and skills can help to ensure that no country is left behind.

That is not only an issue for policymakers and the private sector. Throughout history, transformative change has often started from below. Women’s suffrage, the civil rights movement and climate activism all began with grassroots efforts that grew into powerful forces for change. A similar movement is needed to steer AI in the right direction. Activists can highlight the risks of unregulated AI, and apply pressure on governments and corporations to put human-centered innovation first.

AI’s social, economic and political effects would not naturally bend toward inclusion or equity. Governments must steer incentives toward innovation that augments human potential. Global organizations must establish ethical frameworks to safeguard human rights and data sovereignty. And civil society must hold political and business leaders accountable.

The decisions made today would determine whether AI becomes a bridge or a chasm between the world’s haves and have-nots. International collaboration, ethical governance and public pressure can ensure that we make the right ones.

Shamika Sirimanne is senior adviser to the secretary-general of UN Trade and Development. Xiaolan Fu is professor of technology and international development at the University of Oxford.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

The US Senate’s passage of the 2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which urges Taiwan’s inclusion in the Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise and allocates US$1 billion in military aid, marks yet another milestone in Washington’s growing support for Taipei. On paper, it reflects the steadiness of US commitment, but beneath this show of solidarity lies contradiction. While the US Congress builds a stable, bipartisan architecture of deterrence, US President Donald Trump repeatedly undercuts it through erratic decisions and transactional diplomacy. This dissonance not only weakens the US’ credibility abroad — it also fractures public trust within Taiwan. For decades,

In 1976, the Gang of Four was ousted. The Gang of Four was a leftist political group comprising Chinese Communist Party (CCP) members: Jiang Qing (江青), its leading figure and Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) last wife; Zhang Chunqiao (張春橋); Yao Wenyuan (姚文元); and Wang Hongwen (王洪文). The four wielded supreme power during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), but when Mao died, they were overthrown and charged with crimes against China in what was in essence a political coup of the right against the left. The same type of thing might be happening again as the CCP has expelled nine top generals. Rather than a

Former Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmaker Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) on Saturday won the party’s chairperson election with 65,122 votes, or 50.15 percent of the votes, becoming the second woman in the seat and the first to have switched allegiance from the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to the KMT. Cheng, running for the top KMT position for the first time, had been termed a “dark horse,” while the biggest contender was former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), considered by many to represent the party’s establishment elite. Hau also has substantial experience in government and in the KMT. Cheng joined the Wild Lily Student

Taipei stands as one of the safest capital cities the world. Taiwan has exceptionally low crime rates — lower than many European nations — and is one of Asia’s leading democracies, respected for its rule of law and commitment to human rights. It is among the few Asian countries to have given legal effect to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant of Social Economic and Cultural Rights. Yet Taiwan continues to uphold the death penalty. This year, the government has taken a number of regressive steps: Executions have resumed, proposals for harsher prison sentences