Riding high in the polls, the anti-immigration Alternative for Germany party (AfD) is in a buoyant mood ahead of German elections on Feb. 23. With all other parties forming a “firewall” against it, the AfD is unlikely to get into power this time, but the next election might be a different matter.

Currently in second place behind the center-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Christian Social Union of Bavaria (CSU), the AfD is as close to power as ever before. This has prompted some AfD leaders to promote a softer course, perhaps in the hope of persuading other parties to consider it a viable coalition partner. However, the moderates have lost the argument as the party doubled down on its most radical positions.

For weeks, AfD leader Alice Weidel presented her party as “libertarian-conservative” rather than far right. Her team had even taken the controversial term “remigration” out of the election manifesto since it is used by extremists like the Austrian Martin Sellner, who has advocated the deportations of millions of foreign-born people from Germany, saying even those with residency status or citizenship “might possibly be viable for the remigration policy.”

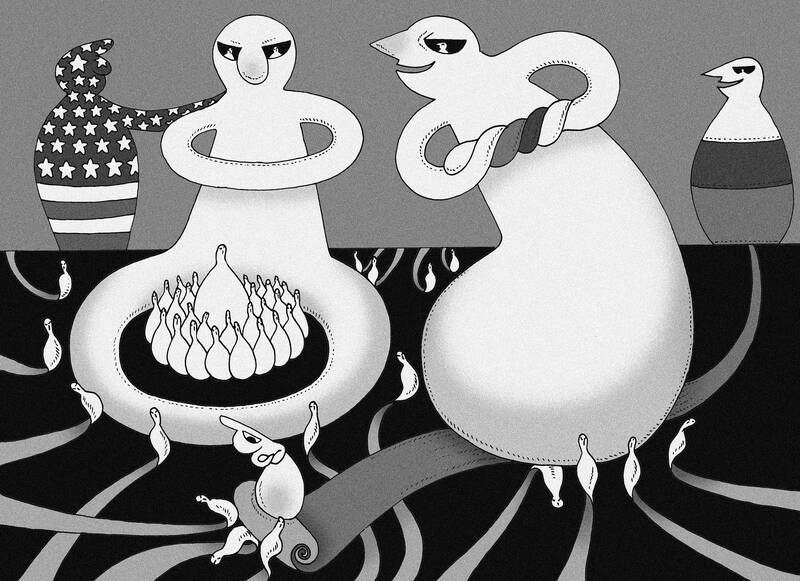

Illustration: Mountain People

Sensing resistance from the powerful radical faction, Weidel changed course. In her fiery speech at the AfD conference this month, she advocated “large-scale repatriations” of immigrants and added: “If it’s going to be called remigration, then that’s what it’s going to be: remigration.”

The term went back into the party program.

Despite the sharpening of the party’s profile, opinion polls predict a vote share of 20 percent and more for the AfD. That is twice the result it achieved at the last election in 2021, but still a long way off from a majority. As is typical in Germany’s electoral system, the AfD would need a coalition partner to be in government. All other parties have vowed to uphold their firewall.

Saskia Esken, leader of Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s center-left Social Democratic Party (SPD), recently questioned on national television whether the conservatives would uphold their firewall “for all eternity.” She is skeptical because there is substantial overlap between the AfD and the conservative CDU/CSU, which is currently predicted to win with around 30 percent. A right-wing coalition with the AfD would create a majority that could tighten immigration policy, lower taxes and loosen economic regulation — things both parties want.

In practice, the CDU/CSU sees many of its core principles violated by the AfD. Founded after World War II, the conservative alliance dominated West German politics for decades. It provided the first postwar chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, who is regarded by many as the founding father of the prosperous, peaceful and democratic Germany that grew out of the ashes of Nazism and war.

Christian-conservative politics was as far right as Germany dared to go after the trauma and guilt associated with the dictatorship, war and genocide. Franz Josef Straus, a prominent conservative of the postwar era, confirmed in 1987 that “there must not be a democratically legitimate party to the right of the CDU/CSU.” The party views itself as the line in modern Germany’s political sand.

Reiner Haseloff, CDU leader of the state of Saxony-Anhalt, recently called this the “foundation myth” of his party, “ruling out” a coalition with the AfD within his lifetime. His party colleague, CDU chair Friedrich Merz, the man most likely to become Germany’s next chancellor, has also argued that a collaboration with the AfD “would kill the CDU.”

There are structural policy differences, too. Adenauer set up the conservative party with an intrinsically transatlantic outlook. This was called “Westbindung,” a binding of Germany to the West, and remains a core principle of CDU/CSU politics today. The AfD, on the other hand, has a strong anti-US streak and wants to tie the country closer to Russia. The manifesto demands “undisturbed trade” with Moscow, the “immediate lifting of economic sanctions” and the “restoration of the Nord Stream pipelines.”

Collaboration with the AfD would go right to the heart of the CDU/CSU, even if some internal party disagreement about this occasionally bubbles to the surface. For now, the AfD must assume that it stands little chance of being approached for a coalition by the likely election winner. So it has not only doubled down on its program, but also on its hostility toward the CDU/CSU. Calling the conservatives a “sham party,” Weidel accused Merz of copying AfD ideas such as border controls to reduce immigration.

The AfD also argues that with the firewall in place, the conservatives have no choice but to form a coalition with parties further to the left, most likely Scholz’s SDP or the Green Party — both part of the defunct ruling coalition. The CDU/CSU was “devoid of any desire for real change,” the AfD claims on the front page of its Web site.

The message that the AfD is the only party for real change is powerful. The firewall forces all other parties into ever greater compromises in order to form coalitions that keep the AfD out. In a recent public conversation with Elon Musk, Weidel claimed they amounted to a “uniparty” giving voters variations on a theme, regardless of how they vote.

The exclusion of the AfD from compromise politics has allowed the party to keep its program radical and discernibly different, which is appealing in itself to many disgruntled voters. Take the AfD’s core issue of immigration, which is consistently the number one topic for voters in the polls. The CDU/CSU has hardened its stance there, but unlike the AfD, it would have to compromise on that since all other parties sit further to the left on this issue.

Weidel was optimistic when she said: “Let us overtake the CDU.”

The election is only one month away and there is a 10-point gap between the parties, but that gap has shrunk in all polls in the last few weeks.

Should Merz win as predicted and form a coalition with one or even two of the parties that were in the deeply unpopular coalition that has just collapsed, he runs the risk of his brand new government starting off with the message that nothing will change. The AfD would sit in opposition with twice the seats and be entirely unrestrained by compromise dynamics. It would be free to criticize the government’s every move and harness people’s anger.

If the next four years continue to frustrate German voters, the AfD’s strategy to stay the radical outlier might well pay off.

As Berlin Mayor Kai Wegner of the CDU put it recently: Germany’s mainstream parties might “have exactly one shot left.”

Katja Hoyer is a British-German historian and journalist. Her latest book is Beyond the Wall: A History of East Germany. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

When US budget carrier Southwest Airlines last week announced a new partnership with China Airlines, Southwest’s social media were filled with comments from travelers excited by the new opportunity to visit China. Of course, China Airlines is not based in China, but in Taiwan, and the new partnership connects Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport with 30 cities across the US. At a time when China is increasing efforts on all fronts to falsely label Taiwan as “China” in all arenas, Taiwan does itself no favors by having its flagship carrier named China Airlines. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is eager to jump at

The muting of the line “I’m from Taiwan” (我台灣來欸), sung in Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), during a performance at the closing ceremony of the World Masters Games in New Taipei City on May 31 has sparked a public outcry. The lyric from the well-known song All Eyes on Me (世界都看見) — originally written and performed by Taiwanese hip-hop group Nine One One (玖壹壹) — was muted twice, while the subtitles on the screen showed an alternate line, “we come here together” (阮作伙來欸), which was not sung. The song, performed at the ceremony by a cheerleading group, was the theme

Secretary of State Marco Rubio raised eyebrows recently when he declared the era of American unipolarity over. He described America’s unrivaled dominance of the international system as an anomaly that was created by the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War. Now, he observed, the United States was returning to a more multipolar world where there are great powers in different parts of the planet. He pointed to China and Russia, as well as “rogue states like Iran and North Korea” as examples of countries the United States must contend with. This all begs the question:

In China, competition is fierce, and in many cases suppliers do not get paid on time. Rather than improving, the situation appears to be deteriorating. BYD Co, the world’s largest electric vehicle manufacturer by production volume, has gained notoriety for its harsh treatment of suppliers, raising concerns about the long-term sustainability. The case also highlights the decline of China’s business environment, and the growing risk of a cascading wave of corporate failures. BYD generally does not follow China’s Negotiable Instruments Law when settling payments with suppliers. Instead the company has created its own proprietary supply chain finance system called the “D-chain,” through which