Former Georgian prime minister Bidzina Ivanishvili has spent much of the past decade gazing down at Tbilisi’s ancient rooftops from his glass castle, a home perched atop a hill that his critics say resembles a Bond villain’s lair.

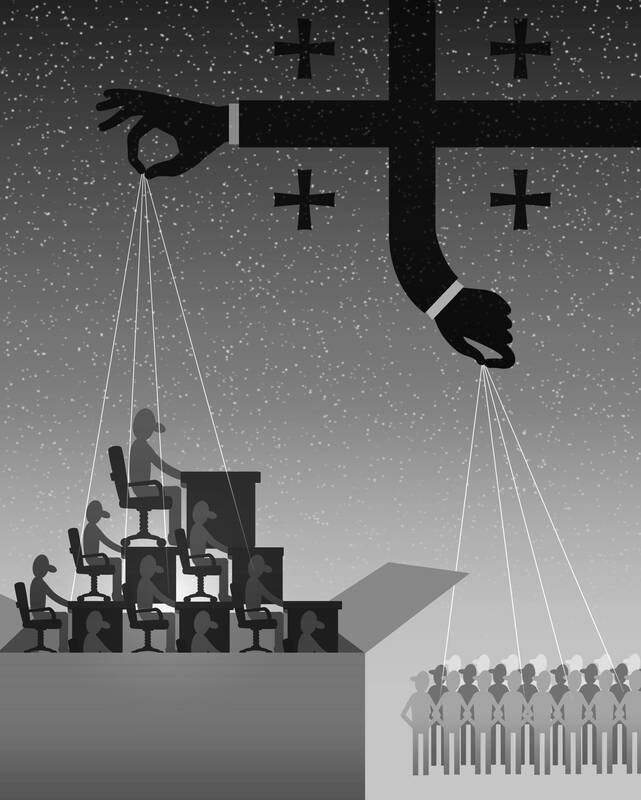

Since his tenure as prime minister from 2012 to 2013, the secretive oligarch has largely exerted his influence from behind the scenes and is widely described by many Georgians as the country’s shadowy “puppet master.”

However, last month, Ivanishvili made a rare public appearance at a pro-government rally to promote a highly controversial “foreign agent” law that has caused the biggest outbreak of unrest in Georgia in years.

Illustration: Yusha

Ivanishvili’s speech was laced with anti-Western sentiments and conspiracy theories, underscoring the extent the small Caucasian country has pivoted away from the West under his guidance.

Opposition parties have long accused Ivanishvili, who made his fortune in Russia in the 1990s, of loyalties to Moscow, Georgia’s Soviet-era overlord, which still regards the south Caucasus as its backyard.

Ivanishvili left rural Georgia in the 1980s to attend university in Moscow, and although other students made fun of his village origins, he has said he understood something that they did not yet: That communism would collapse.

It helped him make his first financial success, selling computers in Russia. Like other future oligarchs at the time, he soon moved into banking and metals, acquiring Soviet-era state assets through privatizations on the cheap. His wealth is estimated at US$6 billion, a sum that exceeds Georgia’s state budget for 2021, although many of his income sources remain murky.

“I could tell you anything and you wouldn’t be able to check it,” he said once.

When he returned to Georgia, he constructed the Tbilisi hill castle, as well as a series of lavish estates across the country. Still, he kept his identity a closely guarded secret, moving around in disguise and lavishing funding on artists or projects he decided he liked.

Ivanishvili spoke to the press for a brief period around 2012, when after years of living anonymously he announced he was running to be prime minister, setting up the Georgian Dream party and claiming he was fed up with the authoritarian bent of the then-government.

In one interview, he arrived at his Black Sea estate in Batumi driving a golf cart playing Frank Sinatra’s My Way, and proceeded to give a tour of his collection of zebras, peacocks and other exotic animals while outlining a vision for Georgia.

At the time, he said: “I will be in the government for a year, or for two years maximum, and afterward I will become an active member of society, to help society learn how to elect people and how to control their politicians. And make sure that there is a free press and a real opposition.”

Although he resigned from public office in 2013, his presence has continued to loom over the country’s politics.

“It is no secret that all the power is concentrated in Ivanishvili’s hands,” said Kornely Kakachia, director of the Tbilisi-based think tank the Georgian Institute of Politics.

Through the years, Ivanishvili has kept up his eccentric antics.

Angering environmentalists, he transformed a park by uprooting and transporting rare, immense trees from remote areas of Georgia to his arboretum in Ureki, a resort town on the Black Sea.

However, more troubling for many Georgians has been his party’s plans to adopt the “foreign agents” law.

The bill has been described by Georgian protesters and Western officials as a “Kremlin-inspired” tool to hound independent media and opposition voices in a country that has long teetered between the Russian and Western spheres of influence, but whose government now appears to be leaning toward Moscow.

The EU has made clear it would freeze Georgia’s membership application to the bloc if Tbilisi enacted the law.

Georgian Dream and Ivanishvili deny leaning toward Russia, and say the measures would increase transparency and defend Georgia’s sovereignty.

Russia is unpopular among ordinary Georgians, having supported armed separatists in the Moscow-backed breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia in the 1990s and again in 2008.

Those who have worked with Ivanishvili say he has grown more authoritarian and ambitious over the years.

“He loves control, he runs the country as his dollhouse,” said Tina Khidasheli, who served as Georgian minister of defense in a Georgian Dream-led government from 2015 to 2016.

Khidasheli said Ivanishvili was aiming to implement the foreign agent law to further strengthen his grip on power before the parliament elections due in October.

“For him, it is all about keeping in power, everything he does is guided by it,” she said.

Khidasheli was troubled by Ivanishvili’s recent statements in which he bemoaned that Western countries were being controlled by a secret global conspiracy that his government was successfully resisting.

He went on to denounce the West as a “global party of war” that was attempting to drag Georgia into conflict with Russia.

“Ivanishvili always had a tendency for conspiracy theories,” Khidasheli said. “The problem is now that his views go completely unchecked.”

One of Ivanishvili’s fiercest critics is incarcerated former Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili, who accuses Ivanishvili of having him arrested on the Kremlin’s orders.

“Georgia has a long history of political vendettas,” Kakachia said. “Whoever comes to power tends to go after his predecessor.”

This means Ivanishvili believes that staying in power is an “existential question,” he added. “It is about personal survival.”

Pjotr Sauer is a Russian affairs reporter for the Guardian. Shaun Walker is the central and eastern European correspondent for the Guardian and author of the book, The Long Hangover: Putin’s New Russia and the Ghosts of the Past.

China has not been a top-tier issue for much of the second Trump administration. Instead, Trump has focused considerable energy on Ukraine, Israel, Iran, and defending America’s borders. At home, Trump has been busy passing an overhaul to America’s tax system, deporting unlawful immigrants, and targeting his political enemies. More recently, he has been consumed by the fallout of a political scandal involving his past relationship with a disgraced sex offender. When the administration has focused on China, there has not been a consistent throughline in its approach or its public statements. This lack of overarching narrative likely reflects a combination

Father’s Day, as celebrated around the world, has its roots in the early 20th century US. In 1910, the state of Washington marked the world’s first official Father’s Day. Later, in 1972, then-US president Richard Nixon signed a proclamation establishing the third Sunday of June as a national holiday honoring fathers. Many countries have since followed suit, adopting the same date. In Taiwan, the celebration takes a different form — both in timing and meaning. Taiwan’s Father’s Day falls on Aug. 8, a date chosen not for historical events, but for the beauty of language. In Mandarin, “eight eight” is pronounced

US President Donald Trump’s alleged request that Taiwanese President William Lai (賴清德) not stop in New York while traveling to three of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies, after his administration also rescheduled a visit to Washington by the minister of national defense, sets an unwise precedent and risks locking the US into a trajectory of either direct conflict with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) or capitulation to it over Taiwan. Taiwanese authorities have said that no plans to request a stopover in the US had been submitted to Washington, but Trump shared a direct call with Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平)

It is difficult to think of an issue that has monopolized political commentary as intensely as the recall movement and the autopsy of the July 26 failures. These commentaries have come from diverse sources within Taiwan and abroad, from local Taiwanese members of the public and academics, foreign academics resident in Taiwan, and overseas Taiwanese working in US universities. There is a lack of consensus that Taiwan’s democracy is either dying in ashes or has become a phoenix rising from the ashes, nurtured into existence by civic groups and rational voters. There are narratives of extreme polarization and an alarming