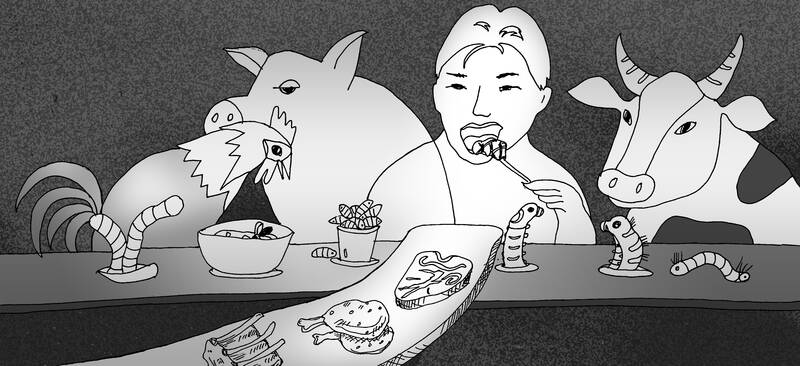

No dystopian picture of a climate-ruined planet is complete until you have been put off your lunch.

Whether it is the grubs farmed by Dave Bautista in Blade Runner: 2049 or Charlton Heston in Soylent Green yelling that food is being made from “people,” there are few things that provoke as visceral a reaction as the prospect that ecological disaster might force you to eat something gross.

It Is hardly surprising, then, if we are regularly promised a future of Blade Runner-style protein farms, where insect larvae are bred en masse for human consumption. “STOP insect flour-based foods in school canteens,” Italian deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini wrote in an X posting last month, echoing a trope that has found currency among the country’s farm protestors.

Illustration: Tania Chou

Not everyone sees this future as a grim one — indeed, for some, it looks more like a utopia. Insects are highly efficient at converting waste matter into high-quality protein, making their consumption a potentially more sustainable way to feed a planet approaching 10 billion people.

New York-based chef Joseph Yoon promotes entomophagy with gourmet dishes such as scorpion rice balls and ant guacamole, while The Economist has been pushing the virtues of bugmeat for so long that it is starting to look like a running joke. “Edible insects can play a vital role in the global food system,” said the authors of a paper last week in Scientific Reports, compiling a list of 2,205 insect species eaten across the world.

The more realistic picture of the future is neither dystopia nor utopia, however — and it is not going to lead to us eating less chicken, pork and beef, either. If anything, the most likely future for insect farming is one where it accelerates humanity’s growing appetite for poultry and mammal flesh, rather than reducing it.

That is because insects are best suited to solving a problem the livestock industry has been struggling with for decades — the protein deficit. Intensive farming depends on getting animals to grow faster, and that requires levels of protein that are rarely found in their natural diets.

Soybeans are not a top-four global crop because of all the edamame, tofu and dairy-free lattes we consume, but because the soymeal left over after oil is squeezed out is about half protein, making it an excellent additive to animal feed. Such protein-rich feed cakes are also one of the main byproducts of the corn ethanol industry.

That is not the half of it. Indeed, a history of the things used to bulk up livestock over the years provides enough horror stories to fill a Black Mirror season.

Chicken manure is a routine high-protein feed ingredient in much of the world, including the US. So is fishmeal, made from rendering fish too small for human consumption into powder. There have even been multiple stomach-churning experiments looking at whether cattle could be fed with their own dung.

Indeed, insect farming would be having a much easier time of things right now if previous attempts to solve the protein deficit had not led to disaster. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy, the brain-wasting condition known as mad-cow disease, appears to have emerged in the UK in the 1980s because cattle were being fed meat and bone meal, another protein-rich feed enhancer. That infected them with scrapie, a degenerative disease present in the brain tissue of the sheep being ground into meal. The resulting public-health emergency led to tighter regulation of the animal-feed chain, so these days the controls are almost as tight as those on human food.

It is the growing awareness of the climate impact of farming that is starting to change that, as well as provoking those protests in Italy and across Europe, many of which are in opposition to increased environmental regulation of agriculture. Emissions from livestock amount to about 3.5 billion metric tonnes a year, equivalent to total climate pollution from the EU and Canada put together. Better management of animal waste — such as feeding manure to insect larvae, which could then be turned into nutritious feed — could play a major role in reducing that burden.

Those hoping that human entomophagy will lead to more sustainable global food systems should be careful what they wish for: The ecologically minded push to include more grubs in human diets is going hand-in-hand with a more hard-headed drive to allow them back into feed troughs, too. The EU allowed insects to be fed to fish in 2017 and to chickens and pigs in 2021.

Horrible food is such a sci-fi staple because people are fussy eaters — one reason that insect farming so far is mostly serving the needs of grub-eating pets, as Bloomberg News reported last month. However, farm animals do not get a choice about their lunch.

If feed pellets made from fly larvae, crickets and mealworms succeed in lowering the cost of producing poultry and livestock meat, it is going to make such products more affordable and increase global consumption. That is unlikely to be a win in climate terms, no matter how efficiently we bulk up our farm animals.

If you are looking for a diet with a lower carbon footprint, you would be better off giving up meat altogether.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. Previously, he worked for Bloomberg News, the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long been expansionist and contemptuous of international law. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), the CCP regime has become more despotic, coercive and punitive. As part of its strategy to annex Taiwan, Beijing has sought to erase the island democracy’s international identity by bribing countries to sever diplomatic ties with Taipei. One by one, China has peeled away Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic partners, leaving just 12 countries (mostly small developing states) and the Vatican recognizing Taiwan as a sovereign nation. Taiwan’s formal international space has shrunk dramatically. Yet even as Beijing has scored diplomatic successes, its overreach

After 37 US lawmakers wrote to express concern over legislators’ stalling of critical budgets, Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) pledged to make the Executive Yuan’s proposed NT$1.25 trillion (US$39.7 billion) special defense budget a top priority for legislative review. On Tuesday, it was finally listed on the legislator’s plenary agenda for Friday next week. The special defense budget was proposed by President William Lai’s (賴清德) administration in November last year to enhance the nation’s defense capabilities against external threats from China. However, the legislature, dominated by the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), repeatedly blocked its review. The

In her article in Foreign Affairs, “A Perfect Storm for Taiwan in 2026?,” Yun Sun (孫韻), director of the China program at the Stimson Center in Washington, said that the US has grown indifferent to Taiwan, contending that, since it has long been the fear of US intervention — and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) inability to prevail against US forces — that has deterred China from using force against Taiwan, this perceived indifference from the US could lead China to conclude that a window of opportunity for a Taiwan invasion has opened this year. Most notably, she observes that

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) said on Monday that it would be announcing its mayoral nominees for New Taipei City, Yilan County and Chiayi City on March 11, after which it would begin talks with the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) to field joint opposition candidates. The KMT would likely support Deputy Taipei Mayor Lee Shu-chuan (李四川) as its candidate for New Taipei City. The TPP is fielding its chairman, Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌), for New Taipei City mayor, after Huang had officially announced his candidacy in December last year. Speaking in a radio program, Huang was asked whether he would join Lee’s