Somalian aid worker Hasan Mohammad Sirat has almost no tools at his disposal to tackle the devastating effects of extreme weather in his war-torn country, where floods this year have followed hard on the heels of a severe drought.

“We are trying our best,” he said, pointing to awareness measures such as teaching camp residents forced to flee violence and hunger to move to higher ground to escape flooding, which has killed nearly 100 people and uprooted 700,000 since October.

Sirat, a field officer with the Iniskoy for Peace and Development Organization, works in a village near Baidoa city in southwest Somalia, an area that is home to one of the country’s largest populations displaced by insurgency and drought.

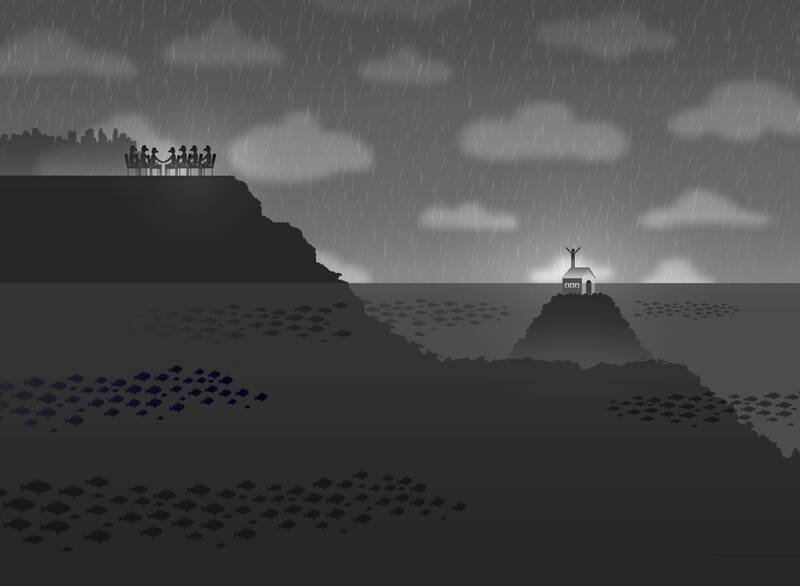

Illustration: Yusha

Last month, floods swept away his uncle’s house and many camp tents and other buildings in the Baidoa area, leaving families exposed to the elements.

“These people, they are vulnerable — these people have no houses, [they] need shelter,” Sirat said.

However, the authorities in Somalia do not have the funding needed to build safer homes, drainage canals or other infrastructure that can help resist climate shocks and stresses, he said.

Here, as in other fragile states such as Afghanistan and Libya, weak governance systems are an obstacle to accessing global funding to enable communities to adapt to a harsher climate and repair the “loss and damage” caused by disasters.

At the COP28 climate summit, governments are expected to endorse a declaration on “climate, relief, recovery and peace” that would aim to channel more support to bolster climate resilience in war-torn and unstable countries.

Currently they receive only a tiny fraction of international funding to tackle climate change, leaving their people highly vulnerable to disasters made worse by global warming, such as the floods that burst decrepit dams in Libya earlier this year.

David Nicholson, chief climate officer for global aid agency Mercy Corps, said donors should stop thinking it is impossible to do adaptation work in politically unstable countries, as the money can be channeled through local governments or groups.

“We need to be able to take this risk — there are successful ways that we can still build resilience to the climate crisis even in these most challenging environments,” he said.

For example, Nicholson’s group has worked with herders and local authorities on northern Kenya’s borders — where scarcer grazing due to drought is causing tensions — to better manage land by combining pastoralist knowledge and remote sensing via satellites.

In the lead-up to COP28, World Food Programme (WFP) executive director Cindy McCain and COP28 president Sultan al-Jaber called for urgent action to increase climate protection in fragile and conflict-afflicted countries.

They said in a joint statement last month that people living in turbulent places such as Somalia get up to 80 times less climate finance than those in stable countries.

The COP28 declaration says that conflict fuels people’s vulnerability and exposure to climate hazards.

In turn, climate change harms incomes, homes and well-being, exacerbating aid needs and posing “a significant and growing challenge to stability,” it says.

WFP climate spokesperson Jenny Wilson said in an e-mail that governments’ commitments at COP28 should “rapidly turn into action plans that provide long-term protection for those in the most fragile and conflict-affected settings.”

Hassan Mowlid Yasin, executive director of the Somali Greenpeace Association, a nonprofit that supports communities to better withstand climate threats, said that his country is seeking more international help to cope with the effects of warming.

“The major problem is that accessing finance is really difficult,” he said in a telephone interview.

Clare Shakya, an adaptation finance expert who has long worked with developing countries, said that all those with “thin” governments, including those at war and small island nations, are struggling to tap into global climate funds.

The process can take several years due to demanding due diligence requirements, she said.

“It’s incredibly high in transaction costs and a country that is distracted by many immediate needs and many immediate emergencies just doesn’t have the capabilities,” Shakya said.

Countries must usually follow the same rigorous rules when applying for funding, favoring larger states with functioning civil service institutions, she said.

Rather than navigating these complex processes directly, Somalia gets its funding through intermediary agencies like the UN Development Programme, Yasin said.

Even as countries with low administrative capacity and weak leadership are struggling to deal with fast-worsening climate change effects, the world is becoming a more dangerous place.

The Institute for Economics and Peace estimated in a report this year that a 25 percent rise in food insecurity increases the risk of conflict by 36 percent, while a 25 percent jump in the possibility of water-related challenges such as drought escalates the likelihood of conflict by 18 percent.

An analysis by Mercy Corps found that the 10 most fragile states received less than 1 percent of total climate adaptation finance in 2021, amounting to just US$223 million.

That year, international funding for adaptation in developing nations dropped 14 percent to US$24.6 billion, even as total climate finance rose by 7.6 percent, data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) showed.

Those figures prompted OECD secretary-general Mathias Cormann to flag “a pressing need for international providers to significantly scale up their efforts” on adaptation finance, in line with a commitment to double it to at least US$40 billion a year by 2025.

Even when money is short for longer-term adaptation, resilience experts say providing aid in the run-up to a disaster can reduce the need for food and other emergency relief later.

In Somalia, with heavy rains forecast, WFP activated its “anticipatory action” program this year, providing people with information and help to protect their homes before flooding hit.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization has estimated that every dollar it has spent on protection before a disaster has produced US$7 in benefits and avoided losses for families.

Yet funding remains an issue even for global agencies such as WFP, which said it would struggle to scale up its anticipatory action work in Somalia without more donations.

Nicholson said that a continued lack of adaptation support for communities in fragile places would force people to migrate away from areas that are no longer liveable.

“It’s going to become such a scale that it’s going to completely overwhelm the geopolitical system and could have pretty devastating effects,” he said.

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s