From cowboys to presidents, supermodels to gardeners, you would be hard-pressed to find someone who does not own a pair of blue jeans. Denim, a heavy-duty cotton twill, is one of our most enduring and versatile wardrobe staples. It could be deep indigo or faded blue; high-rise or low-rise; made into dresses, shirts, skirts and even tuxedos (although I would add that just because it can, that does not mean it should). Yet with more than 1 billion pairs of jeans sold every year, the fabric also comes with a heavy environmental cost.

Let us imagine your favorite jeans. They started off in a field of cotton — or more likely hundreds of different fields — probably in India, China, the US, Brazil or Pakistan, the five countries that make up 75 percent of global cotton production.

Once the fibers have been separated from the seeds, in a process known as ginning, they will be spun into yarn and subsequently dyed. For denim, that usually means an indigo dye. Once woven and sewn into garments, fashionable faded looks are created through finishing processes such sandblasting, stonewashing and acid-washing. It is a long and complicated supply chain spanning multiple countries and businesses.

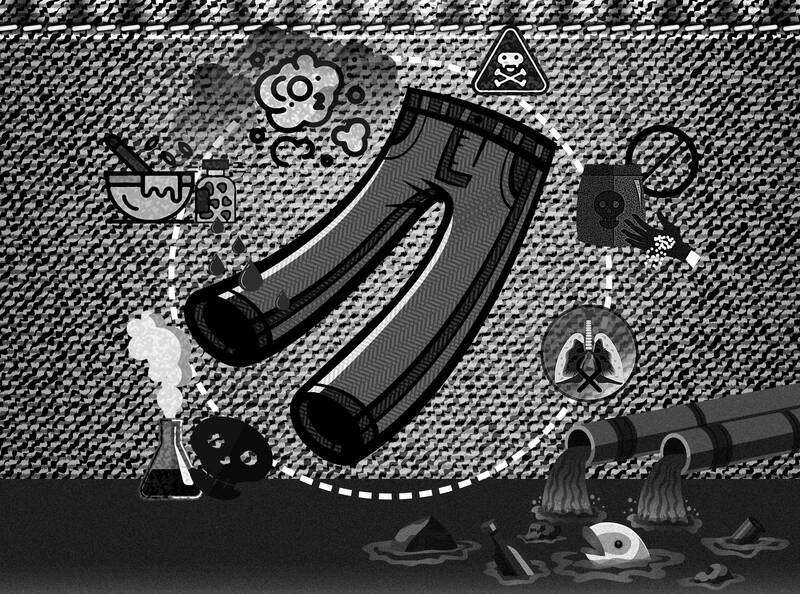

Illustration: Louise Ting

Every step comes with a significant environmental effect. According to Levi Strauss & Co, in 2015 a pair of 501 jeans — the company’s signature cut — used nearly 3,000 liters of water and emitted 20kg of CO2e (a measure that encompasses all greenhouse gases) by the time it hit the shop floor. Prolific use of pesticides and fertilizers are bad for both nature and human workers. Indigo dye used to be completely natural, made from the leaves of the Indigofera tinctoria plant — true indigo. Now, however, the vast majority of dye is synthetic and contains toxic pollutants, including formaldehyde and cyanide.

In some parts of the world, waste from the dye process is dumped straight into waterways, tinting rivers the colors of the forthcoming fashion season. Finishing processes can be equally polluting, resource-intensive and dangerous for workers who, too often, are not given the right protective equipment.

Of course, many of these problems are not restricted to denim production. Cotton is used in about half of all textiles. Yet the ubiquity of blue jeans makes them a powerful symbol. What would it take to turn them green?

The first step is making denim’s origins completely traceable. If a brand does not know what is happening in its supply chain, then it cannot ensure that it is making a positive impact — or not having a negative one.

That is more complicated than it sounds. A yarn could contain cotton from hundreds of small farms, as bales of ginned cotton are blended to achieve the desired quality and specifications. Large clothing companies are also extremely fragmented, with everyone working in their own silos, as designer Anne Oudard and sustainable denim consultant Ani Wells explained to me.

Recounting one honest answer they got from someone in the industry, Wells said: “They’re like: ‘I’m too stressed already. That’s the other person’s job, why do I have to think about that, too?’”

The first in a series of denim research studies by Oudard and Wells used the example of a designer sampling a garment in a traceable organic denim. Yet there are conflicting responsibilities: By the time the style is produced, buying teams might have chosen a cheaper fabric to reduce costs. Equally, no one person at these companies knows everything about a pair of jeans, so information — such as whether certain suppliers have been audited or not — could slip through the cracks.

It ought to be possible — cotton is not a gas; it is a valuable, physical commodity. Coffee and cocoa have lessons to offer after big pushes to increase the traceability of those goods. Oudard and Wells both agree that cotton traders — typically the middlemen between farmers and spinners — have a big role to play in helping improve their commodities’ traceability and sustainability. There is a trend now to cut them out and go straight to the farm, but their knowledge is integral.

There is also plenty of innovation in the sector aimed at cleaning up denim’s life cycle. Good Earth Cotton is a regenerative producer that aims to enhance soil carbon uptake and improve biodiversity with its growing methods. FibreTrace incorporates luminous fibers into textiles to create a supply chain that is fully traceable from field to shelf. Huue is creating nontoxic biosynthetic indigo out of sugar. Xeros Technology has developed reusable polymer spheres to replace pumice stones in denim finishing and halve the amount of water needed for the process.

Yet there is one drawback: the expense.

Though there are some innovative brands willing to invest, Wells said that brands typically want to keep things cost-neutral, making it much harder for sustainable startups to scale and subsequently lower prices. The current economic environment is no help. Levi Strauss, for example, just cut its full-year sales outlook as inflation squeezes customers’ purchasing power. Brands might be wary of raising prices more than they need to.

Cost-neutrality is perhaps one of the reasons the Better Cotton Initiative has been so successful, counting many big fashion retailers including Marks & Spencer Group PLC and Hennes & Mauritz AB as members. The sustainability program does not place a price premium on its cotton, unlike organic or regenerative fibers, which could cost as much as 20 percent more, and does not have the same stringent certification requirements as organic standards do — pesticides are allowed, for example — but it does work with farmers to help them reduce water and chemical use and respect workers’ rights. It is been effective at making inroads into the industry — about 22 percent of global cotton production is Better Cotton, compared with organic cotton, which accounts for just 1 percent of global production.

It is a good start, but it is important to remember that growing is only one part of denim’s environmental impact. Which brings me to the final challenge to overcome. Since there is no definition of what a sustainable pair of jeans looks like, brands are free to dictate their own standards. “The problem that we have at the moment is that brands are asking for things from their own perspective, usually with marketing and communication targets and mindsets,” explains Oudard. “They want things they can talk about, and some topics in sustainability are not sexy, but they might have a higher impact.”

That might be hard in an industry based on appearances, but if we are going to make truly planet-friendly jeans, companies will have to immerse themselves in every part of their products’ life cycles, break down those silos and swallow some higher costs.

Lara Williams is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering climate change. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Jan. 1 marks a decade since China repealed its one-child policy. Just 10 days before, Peng Peiyun (彭珮雲), who long oversaw the often-brutal enforcement of China’s family-planning rules, died at the age of 96, having never been held accountable for her actions. Obituaries praised Peng for being “reform-minded,” even though, in practice, she only perpetuated an utterly inhumane policy, whose consequences have barely begun to materialize. It was Vice Premier Chen Muhua (陳慕華) who first proposed the one-child policy in 1979, with the endorsement of China’s then-top leaders, Chen Yun (陳雲) and Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平), as a means of avoiding the

As the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) races toward its 2027 modernization goals, most analysts fixate on ship counts, missile ranges and artificial intelligence. Those metrics matter — but they obscure a deeper vulnerability. The true future of the PLA, and by extension Taiwan’s security, might hinge less on hardware than on whether the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) can preserve ideological loyalty inside its own armed forces. Iran’s 1979 revolution demonstrated how even a technologically advanced military can collapse when the social environment surrounding it shifts. That lesson has renewed relevance as fresh unrest shakes Iran today — and it should

The last foreign delegation Nicolas Maduro met before he went to bed Friday night (January 2) was led by China’s top Latin America diplomat. “I had a pleasant meeting with Qiu Xiaoqi (邱小琪), Special Envoy of President Xi Jinping (習近平),” Venezuela’s soon-to-be ex-president tweeted on Telegram, “and we reaffirmed our commitment to the strategic relationship that is progressing and strengthening in various areas for building a multipolar world of development and peace.” Judging by how minutely the Central Intelligence Agency was monitoring Maduro’s every move on Friday, President Trump himself was certainly aware of Maduro’s felicitations to his Chinese guest. Just

On today’s page, Masahiro Matsumura, a professor of international politics and national security at St Andrew’s University in Osaka, questions the viability and advisability of the government’s proposed “T-Dome” missile defense system. Matsumura writes that Taiwan’s military budget would be better allocated elsewhere, and cautions against the temptation to allow politics to trump strategic sense. What he does not do is question whether Taiwan needs to increase its defense capabilities. “Given the accelerating pace of Beijing’s military buildup and political coercion ... [Taiwan] cannot afford inaction,” he writes. A rational, robust debate over the specifics, not the scale or the necessity,